Tulips are recognized worldwide as harbingers of spring. In New York City, they crop up along Park Avenue and throughout the city’s parks; the Srinagar Tulip Festival in Kashmir, India, is the largest in Asia; and, of course, spring in the Netherlands sees upwards of 7 million tulips blossom across the country.

Tulip’s widespread popularity has also led them to become perennial muses for artists, a reliably understood symbol of spring and a cornerstone of vibrant, nature-inspired landscapes. Their near omnipresence both in life and art raises the question of where they are native to, what their historical and cultural significance is—and how artist’s employment of them in their work has evolved over the centuries. As we approach spring’s zenith and the height of tulip season, learn more about the history of this widely beloved floral motif.

The Origins of the Tulip (And Its Name)

Jug with tulip decoration, Ottoman (16th century). Collection of the Princeton University Art Museum.

The tulip is thought to have originally been native to the Central Asian mountain ranges of Tien-Shan and Pamir-Alay, a region nestled between modern day Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and far western China. From here, the wild blooms spread widely, including to the western most regions of the Asian continent, specifically the Caucuses and Anatolian Peninsula within the Ottoman Empire. The name “tulip” derives from the Persian word for “turban,” and early as 1,000 C.E., wild tulips were being cultivated and propagated.

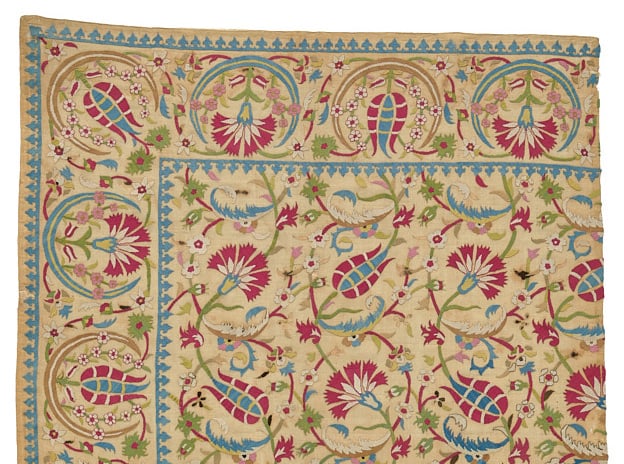

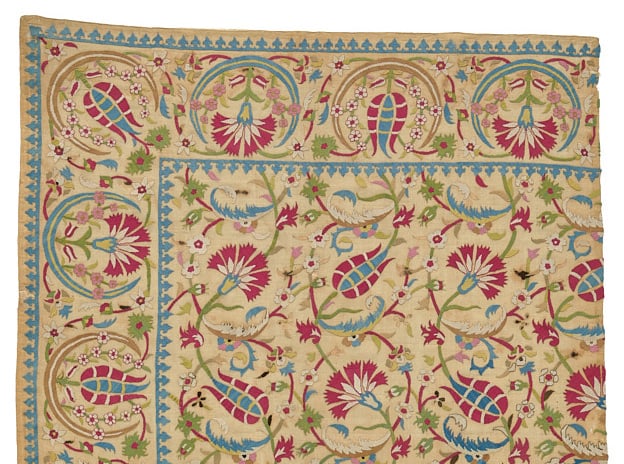

Detail from a section of an embroidered cover, Ottoman (16th or early 17th century). Collection of the Textile Museum, George Washington University.

The tulip motif was quickly adopted as part of the visual culture of the Ottoman empire and proliferated throughout both the decorative and fine arts, appearing in everything from tile and ceramics, carpets and tapestries, to paintings and illuminated manuscripts. Their symbolic meaning was incredibly dynamic and had a distinct spiritual and mystical element. Along with symbolizing beauty, love, and abundance, it is also understood to have been considered a potent ward against evil and conduit for spiritual meditation, as evidenced by its depiction on talismans and its use in decorating Islamic religious sites.

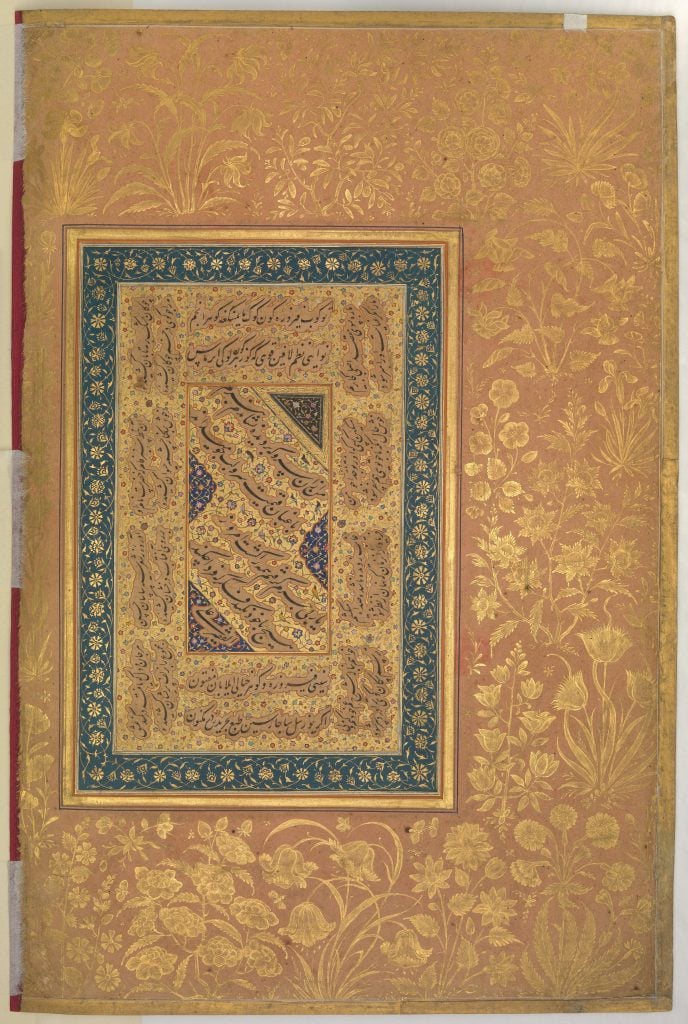

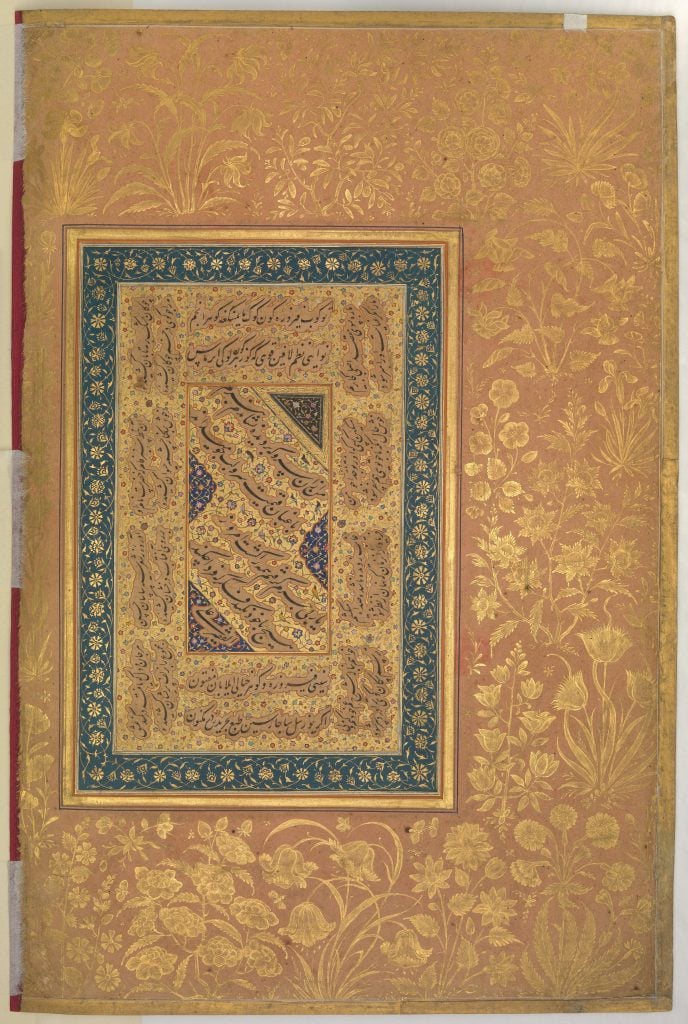

“Portrait of Mulla Muhammad Khan Vali o Bijapur,” Folio from the Shah Jahan Album, verso, (1537–47). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Gardens were an important part of Ottoman culture, influenced heavily by the garden designs of Persia—and in turn influencing the gardens of Western Europe. With the introduction of domesticated, cultivated tulips, they soon became a widely popular element of Ottoman Garden design. Sequentially, the flower became a common motif in art depicting gardens, and a symbol of the elaborate and luxurious Ottoman gardening culture.

Tulip Mania in the Netherlands

Jacob Vosmaer, A Vase with Flowers (ca. 1613). Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

There is no other period of art history more closely associated with tulips than the Dutch Golden Age. Marked by economic prosperity, scientific discovery, and flourishing arts and culture, the tulip came to be a hallmark of the Netherland’s successes. There is some disagreement about exactly when and by whom the first tulips were brought to the Dutch Republic, but it is known that they were imported from the Ottoman Empire sometime in the latter half of the 16th century. Already a costly commodity, the demand for specific bulbs of different colors and varieties quickly outpaced the supply of tulips—and thus Tulip Mania, or the Tulip Craze, began. At its height, the price for a rare and prized tulip bulb was on par with a craftsperson’s annual wage.

Hans Bollongier, Floral Still Life (1639). Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

Coinciding with the tulip craze and economic prosperity of the region was the rise of Calvinism, which led to religious painting and church decoration falling out of favor. With a new, wealthy class of citizenry still hungry for luxuries, landscape, genre, and most importantly as it pertains to tulips still life painting exploded in popularity. Of the broad typologies of the Dutch still life— which included more austere breakfast vignettes, lavish pronkstilleven (roughly meaning “ostentatious” or “ornate” still life), and vanitas—the floral still life was highly prized and remains a recognizable symbol of the period today.

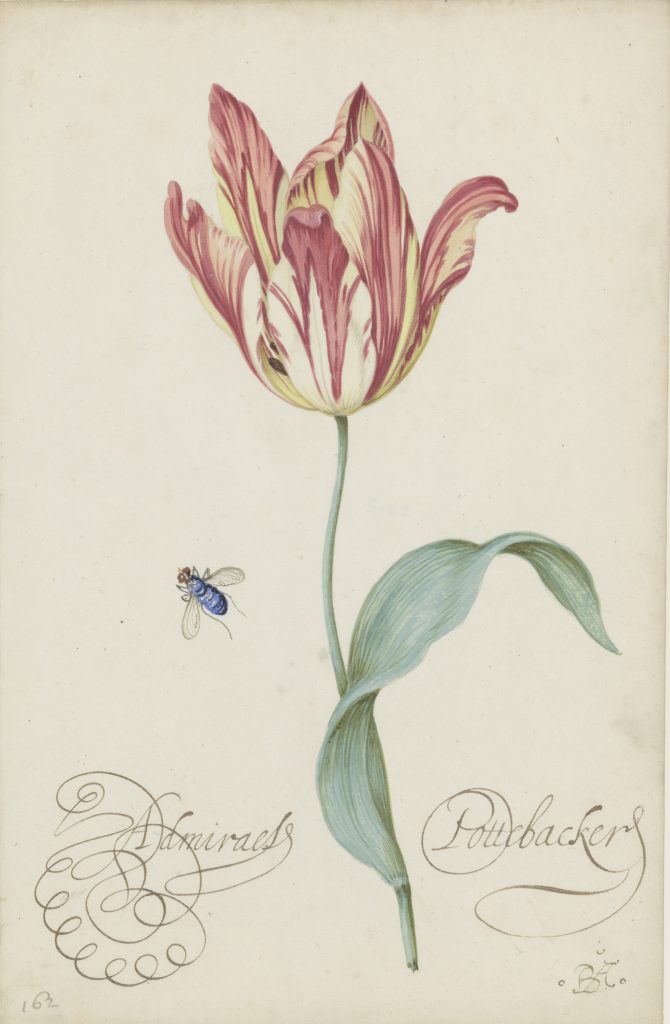

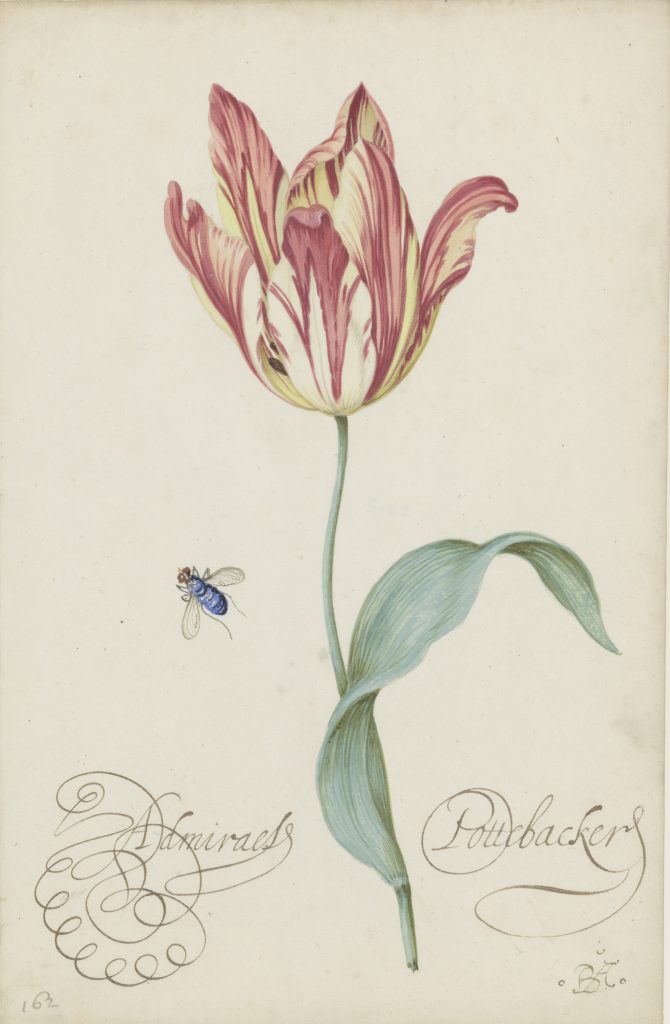

Study of a tulip (Admiral Pottebacker) and a fly (ca. 1620-1629). Found in the collection of Fondation Custodia. Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

Because of the high price of tulips, particularly rare varieties such as the “Semper Augustus,” a white bloom with bright red, broken streaks, many artists were only able to work with print reproductions of certain tulips. The tulip represented wealth and fortune, both for the individual who owned the painting or flower, but also of the nation. However, the concept of memento mori—a reminder that death awaits us all—would also have been immediately recognizable to the period eye. The tulip has a relatively short-lived bloom, lasting only one to two weeks. Particularly within a religious context where piousness was prized, the symbol of a flower, particularly portrayed in various states of bloom and wilt, would on some level allude to the inescapability of death and final judgment—the memento mori was “baked in.”

Jacob Marrel, Still Life with a Vase of Flowers and a Dead Frog (1634). Collection of the Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

The tulip market ultimately deflated in the 1630s, but the love of tulips endured. The blossoms continued to feature heavily in Dutch art for the next century, and the flower and its cultivation are cornerstones of Netherlandish culture today.

It is interesting to note that in the 18th century, the Ottoman Empire experienced a similar tulip craze that led to what is known as the Tulip Period, or Tulip Era. Driven by court society and their embrace of the tulip as a symbol of nobility, luxury, and prosperity—both for the nobles themselves and the empire overall. Despite only lasting from 1718 to 1730, it was a period of peace that saw immense growth in the art and architecture.

A 19th-Century Universal Symbol of Spring

Claude Monet, Tulip Fields near the Hague (1886). Collection of the Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

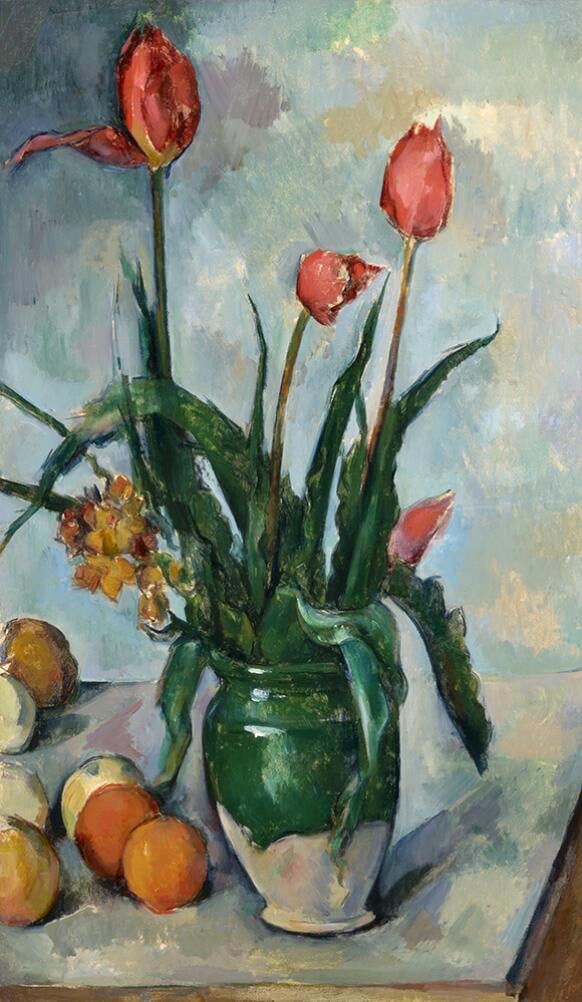

By the 19th century, the tulip’s religious or spiritual associations had largely faded in the West, and they became recognized more pervasively as a symbol of spring and a compelling compositional motif. The region of Holland in the Netherlands had solidified its standing as a bastion of tulip cultivation, and with the rise in popularity of en plein air painting, Claude Monet immortalized the vivid fields of bright flowers—once noting to a friend that the view was “impossible to convey with our poor colors.” Other notable Impressionist’s, from Édouard Manet to Paul Cézanne drew from the tradition of floral still lifes, immortalizing the spring blooms in their own distinctive style.

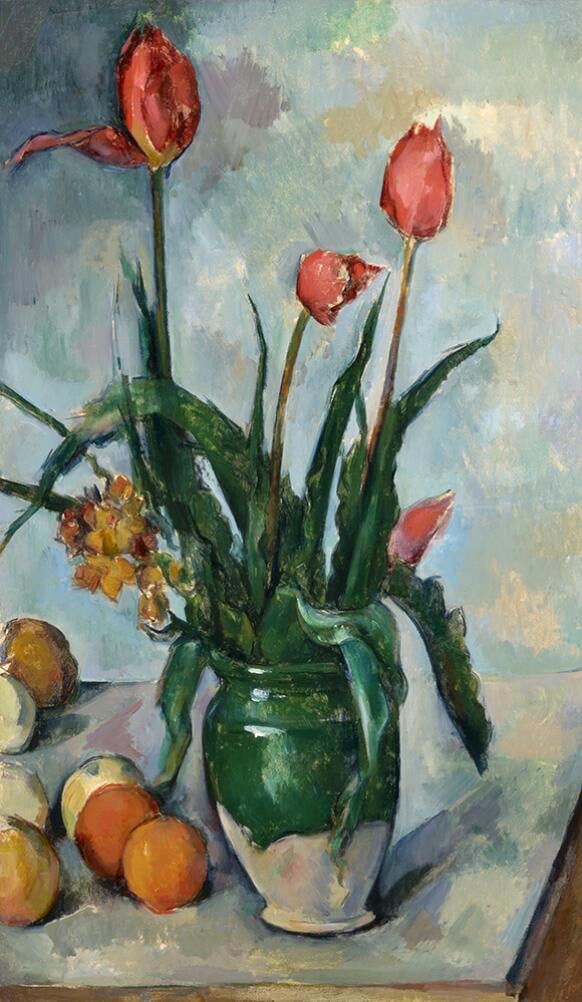

Paul Cézanne, Tulips in a Vase (1888–1890). Collection of the Norton Simon Museum, Pasadena.

Across the Atlantic, tulips were fast becoming a mainstay of American folk art. The flowers were introduced to the continent relatively shortly after their import to Holland, with bulbs being brought over in the early 1600s. By the 19th century, the tulip’s prevalence across American folk art and craft was extensive. Featured in wood carving, textiles, ceramics, paintings—and even butter molds—the tulip motif proved to be highly adaptable, as its streamlined silhouette could be either geometrically simplified or conversely exaggerated to convey exoticism or luxury.

Attributed to Maria Laumennij, Horizontal panel of birds and tulips (1827). Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

The tulip motif was of particular import within the history and tradition of the Pennsylvania Dutch. Comprised of Protestant German immigrants who settled in some regions of Pennsylvania around the turn of the 18th century and their descendants, the community was relatively insular, which led to a distillation of visual culture resulting in a rich and distinct folk art and craft tradition. With a penchant for using bright colors, symmetrical designs, and depicting flora and fauna, Pennsylvania Dutch folk art frequently employed the tulip, which embodied the prevailing aesthetic preferences. Appearing on everything from wooden chests to embroidery, the Pennsylvania Dutch garnered a reputation especially for their quilts as well as “Fractur.” Fractur are works on paper completed in ink and watercolor, and most closely correspond to the tradition of illuminated manuscripts as they frequently adorned significant documents or texts, such as birth or marriage certificates, but were also used simply as an outlet for creative expression.

Tulip Quilt (ca. 1850–80), American. Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Gift of Robert E. Cole, in memory of Helen R. Cole, 1998.

Modern Inspiration and Contemporary Muse

Dining room with a round table and seating by Finnish architect Eero Saarinen (manufacturer: Knoll). Photo by Kühn/ullstein bild via Getty Images.

The tulip as a compositional silhouette underwent profound transformation in the 20th century. In 1911, architect Frank Lloyd Wright completed the Lake Geneva Hotel commission located in southern Wisconsin. The upper stories of the building featured leaded windows with highly geometricized and simplified tulip motifs, a style that both Wright and ultimately the Prairie School movement came to be recognized for. On the other end of the spectrum, and forgoing the strict lines and angles of Wright, architect Eero Saarinen designed the iconic Tulip Table and Chair in the mid-1950s for furniture manufacturer Knoll International. Taking inspiration from the way the tulip blossom sits atop a slender stem, Saarinen emulated the silhouette by using a then-innovative pedestal design.

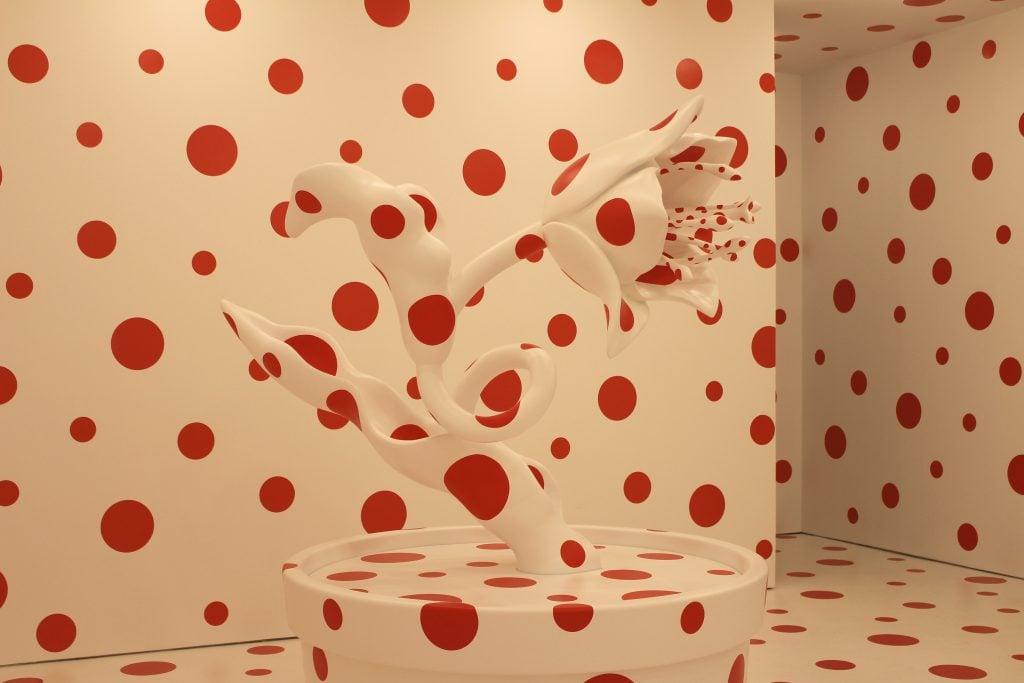

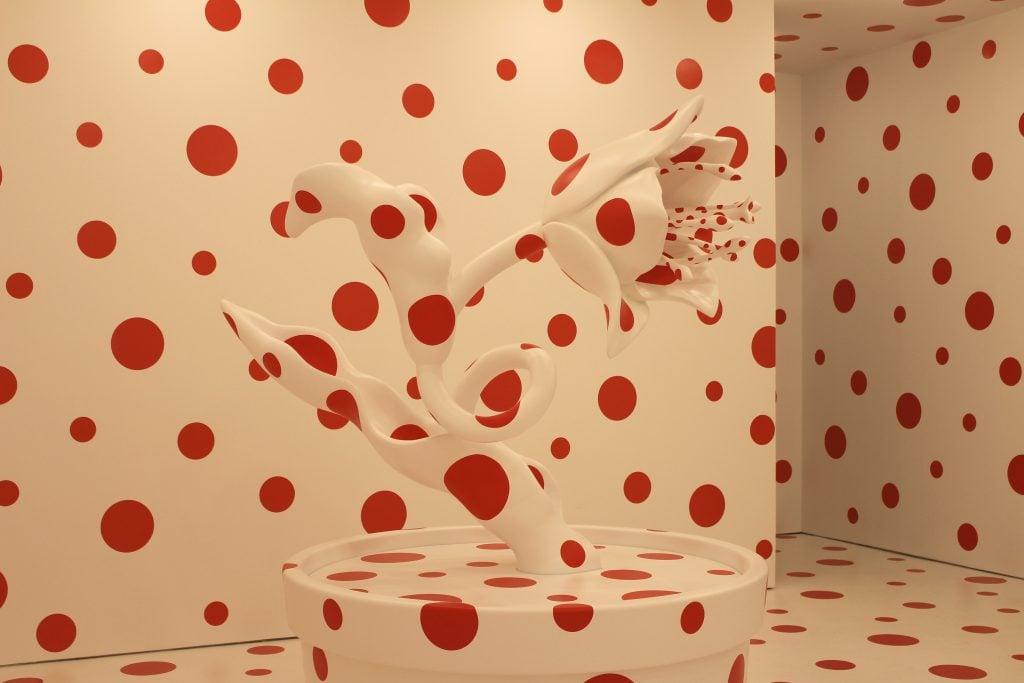

Installation view of Yayoi Kusama, “With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever,” (2017). David Zwirner Gallery, New York. Photo by Stephanie Ott/picture alliance via Getty Images.

Within the realm of fine art, tulips continue to capture the minds and imaginations of contemporary artists worldwide—in arguably much the same way they did Turkish artisans centuries prior. Symbolizing spring and perfect or true love, the tulip is embraced across cultures for its beauty and grace. Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama has frequently employed the tulip motif in her work; one of her more monumental depictions of tulips can be seen in the work With All My Love for the Tulips, I Pray Forever (2011). An immersive piece featuring fiberglass-reinforced plastic potted tulips that are oversize, the flowers, pots, and every surface of the room are covered in her signature polka dots, evoking other famous works like her famous Obliteration Rooms.

Installation view at the Petit Palais, Paris, of Jeff Koons, Bouquet of Tulips (2019). Photo by Bertrand Rindoff Petroff/Getty Images.

More recently, and causing quite the sensation, in 2016 Jeff Koons announced he would bequeath a sculpture to the city of Paris in commemoration of the victims of the French terrorist attacks. Bouquet of Tulips was installed outside of the Petit Palais in Paris, featuring a colossal hand holding a bunch of Koons’ signature balloon tulips. Koons has previously made numerous oversize tulip balloon sculptures as part of his “Tulips” series (1995–2004). Inspired by the flower’s Minimalist silhouette and exuberant colors, the sculpture according to Koons is meant to “represent loss, rebirth, and the vitality of the human spirit.”