Art History

Art Bites: Michelangelo’s Poem About How Much It Sucked to Paint the Sistine Chapel

“I am not in the right place," the Old Master wrote. "I am not a painter."

“I am not in the right place," the Old Master wrote. "I am not a painter."

Richard Whiddington

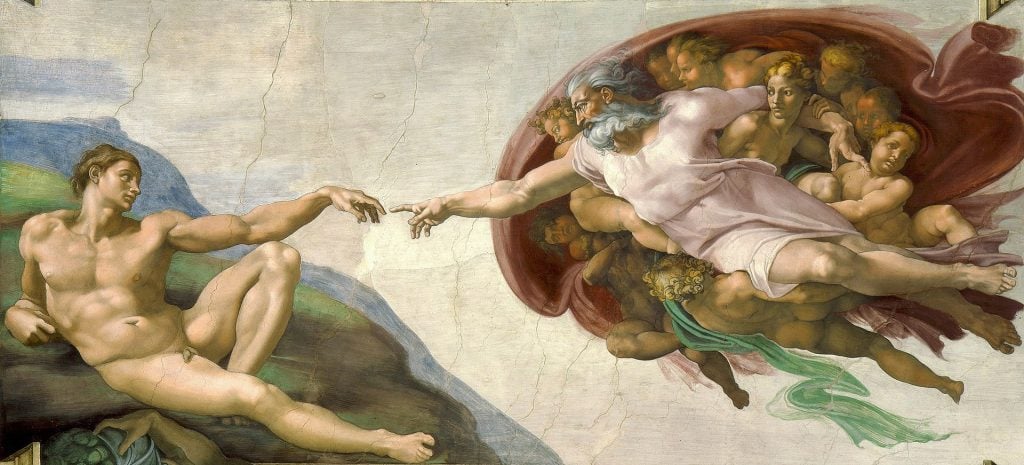

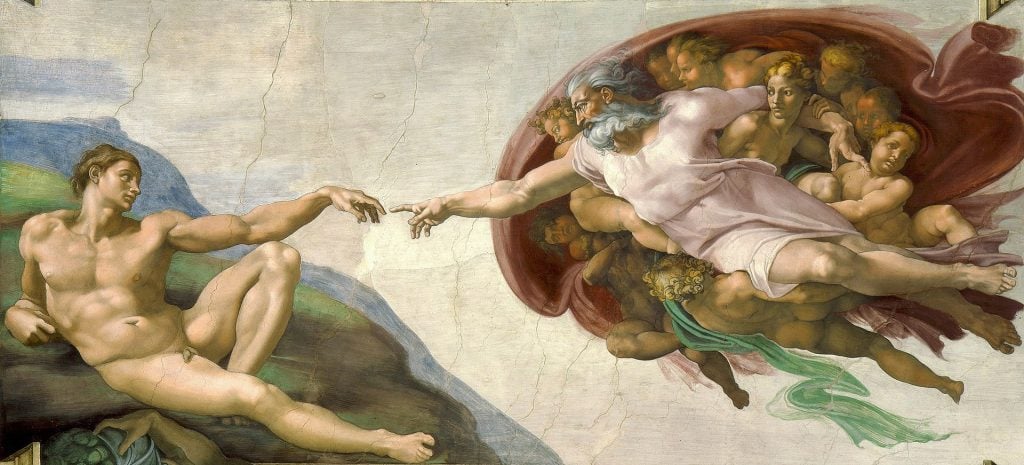

Michelangelo may have immortalized himself by painting the ceiling (and altar wall) of the Sistine Chapel, but he broke his back doing so. And boy, did he moan about it.

In the Renaissance equivalent of a self-pitying voice note, Michelangelo sent his pen pal Giovanni da Pistoia a sonnet bemoaning the toils of beautifying the most sacred space in Christendom on behalf of Pope Julius II. He wrote the poem in 1509, a year into his four-year ordeal and already his complaints and ailments were many.

He had an enlarged thyroid gland (known as a goiter), his spine was crooked and knotted, his chest was tight and twisted, his thighs cramped constantly, and his ass ached from strain. The sucker punch? The paint that dripped steadily from his brush and onto his face.

“My brush / above me all the time, dribbles paint / so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!” he wrote.

The reason for such discomfort was the posture Michelangelo adopted to paint the 11,000-foot ceiling. Contrary to popular imagination, and as portrayed by Charlton Heston in the 1965 film The Agony and the Ecstasy, the Florentine artist worked standing up. His neck was bent backward and his arm raised high above his head. He illustrates the point in his poem to Giovanni with a caricature of a man straining ever upward.

A consequence of working in pain and largely alone on precarious scaffolding — 60-feet high — was that Michelangelo was trapped with his thoughts. He began to have doubts, ones he described as “crazy.” He worried painting in such an unnatural position would lead to bad work. “The painting is dead,” he wrote, adding “I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.”

A little melodramatic to be sure, but it’s worth remembering Michelangelo considered himself a sculptor, not a painter. When Pope Julius II asked the 33-year-old artist to tackle the ceiling, he was hard at work on the pontiff’s marble tomb and had never before completed a fresco. Refusing a pope was somewhat impossible in 16th-century Europe, but Michelangelo tried—twice, in fact. Once in 1508 and a second time in 1509 when he begged to be relieved of work after mold ruined months of work.

It’s fair to say Michelangelo’s ceiling was as much a labor of hate as a labor of love.

Here’s the poem in its entirety:

I’ve already grown a goiter from this torture,

hunched up here like a cat in Lombardy

(or anywhere else where the stagnant water’s poison).

My stomach’s squashed under my chin, my beard’s

pointing at heaven, my brain’s crushed in a casket,

my breast twists like a harpy’s. My brush,

above me all the time, dribbles paint

so my face makes a fine floor for droppings!My haunches are grinding into my guts,

my poor ass strains to work as a counterweight,

every gesture I make is blind and aimless.

My skin hangs loose below me, my spine’s

all knotted from folding over itself.

I’m bent taut as a Syrian bow.Because I’m stuck like this, my thoughts

are crazy, perfidious tripe:

anyone shoots badly through a crooked blowpipe.My painting is dead.

Defend it for me, Giovanni, protect my honor.

I am not in the right place—I am not a painter.