Art World

Art Bites: Why Are Medieval Babies So Ugly?

Fashions set by depictions of Jesus impacted how babies were painted for hundreds of years.

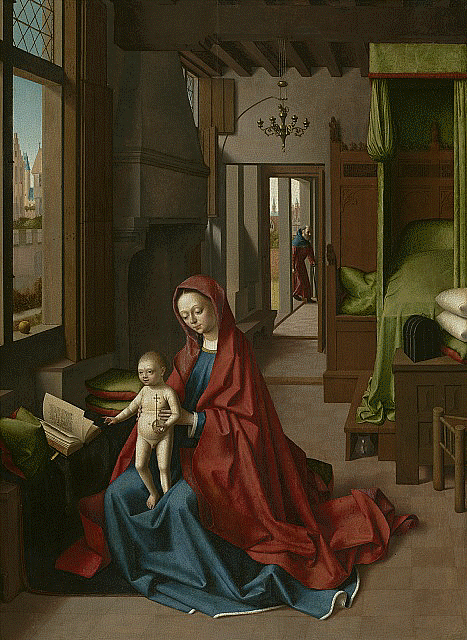

Ever walked through the Medieval section of a museum and noticed that all of the babies are, well, just a bit ugly? They often have fully developed use of their necks, may be doing distinctly un-babyish things, and regularly look like furious old men. Some even appear to have male pattern baldness.

But why? Hadn’t the artists ever seen a baby? That seems unlikely. Well, it’s partly down to attitudes towards depicting the world’s most famous baby: Jesus.

The “Homuncular Jesus” refers to the way that the infant Jesus was portrayed in art. “Homunculus” comes from the Latin meaning “little man,” and that’s exactly how artists portrayed Jesus. The infant Christ wasn’t shown as a defenseless baby, but rather as a smaller version of his adult self. Artists wouldn’t dare to paint Jesus, or other Biblical babies, like John the Baptist, as weak. Speaking to Vox in 2015, historian Matthew Averett explained how there was an “idea that Jesus was perfectly formed and unchanged, and if you combine that with Byzantine painting, it became a standard way to depict Jesus.”

Duccio’s Maestà (ca. 1311).

Most paintings in this time period were of Biblical subjects and were commissioned by the Catholic church, or by wealthy patrons of the church, so naturally people wanted their babies to fit with the standard set by Jesus.

Another reason for the oddity of Medieval babies is that realism and idealism simply didn’t matter as much for artists working before the 15th century. Naturalism wasn’t a top priority, and this also meant that it was less important for people to look distinct from each other. Their painted image wasn’t necessarily meant to mirror their actual looks, more to be a representative for them. That’s why many figures in portraits appear indistinguishable from one another, even when painted by different artists in different decades.

These two trends didn’t go out of style until the Italian Renaissance, and even then old habits die hard and a few ugly babies did slip through. Interest in this quirk of art history has certainly not abated, there’s even a X (formerly Twitter) account dedicated to the phenomenon, fittingly under the handle: UglyArtBabies.

Master of the Altarpiece of Saint Bartholomew, The Virgin of the Walnut (ca.1485-1490). Wallraf-Richartz Museum. Cologne. Germany. Photo by: PHAS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

The Madonna of the Goldfinch (1507) . Photo by Art Media/Print Collector/Getty Images.

Matteo di Giovanni, Madonna and Child (ca. 1450-1495). Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Bernardino Fungai, Madonna and Child with Two Hermit Saints (15th century). Photo by: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

Petrus Christus, Virgin and Child in a Domestic Interior (ca.1460-1467). Courtesy of the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art.