Opinion

From Immersive Everything to the Rise of Museum Unions, These 7 Trends Defined the Art World in 2021—and Will Shape the Year to Come

A look at the movements that defined 2021 in the art world, and how they may evolve in the year ahead.

A look at the movements that defined 2021 in the art world, and how they may evolve in the year ahead.

Ben Davis

Happy New Year. As we start again, here’s a list of some of the topics that seemed to shape art in 2021—and how they are likely to evolve in 2022.

A visitor peers at Es Devlin’s mirrored maze Forest of Us at Superblue Miami on August 31, 2021. Photo by Chandan Khanna/AFP via Getty Images.

Immersive Van Gogh ruled the year, with multiple versions of the phenomenon competing across the map for the Big Fun Art dollar. Following Van Gogh’s lead, scads of companies started experiences inspired by pretty much any artist with any name recognition whatsoever, from three separate immersive Monets, to immersive Frida and Diego (“Mexican Geniuses“), to immersive Francisco Goya (“InGoya“).

Meow Wolf, the experience-art collective turned experience-art company, opened large new environments including its “Omega Mart” in Vegas, which was part of Area15, a dedicated immersive-experience zone in Sin City. Meanwhile, Superblue, the Pace-affiliated Big Fun Art emporium, opened a dedicated space in Miami, before Superblue’s curators realized a show of the design-art group DRIFT at the Shed, filling the space with the spectacle of gravity-defying stone blocks.

In the hazy post-vax, pre-Omicron days of mid-2021, people were looking to get back out into the world and be around people, and the popularity of these para-art attractions became one of the manifestations of that urge. And yet, these were all definitively high-tech types of events, privileging the digital augmentation of existing art and interactivity over the traditional art object and, you know, just looking. Crowds in Columbus, Ohio that turned out for “Through Van Gogh’s Eyes” at the local museum were said to be disappointed that it was just the boring old real thing, not the fun new digital Van Gogh.

So, above all else, the popularity of Immersive Everything spoke to the way in which a year-long period of cultural life existing mostly on tech platforms rewired how people think about culture, giving “art” a permanent cyborg makeover.

Which brings me to…

Pak’s Mass Banner. Courtesy Nifty Gateway.

This happened fast, didn’t it? For years, galleries had sought to find a way to get tech money excited about collecting contemporary art, to no avail. 2021 was the year that all changed—sort of. It may be more accurate to say that technologists and investors just went and found themselves an art world of their own, partly made in their image of mercurial financial flows and “the-internet-will-save-us” evangelism. Because tech and finance are so dominant in shaping the desires and aspirations of society already, it was really not hard to shift the entire cultural conversation in that direction, and fast.

The truly gigantic prices for NFTs at auction made them a pop-culture phenomenon, even if the $69 million sale of Beeple’s Everydays in March 2021 at Christie’s seems to have been above all a spectacular piece of marketing to say “this is real,” get everyone engaged with NFTs, and thus give cryptocurrency an actual use. Nothing has quite matched that high since (unless you count the numbingly complex dynamics of Pak’s Merge sale for Nifty Gateway of hundreds of linked NFTs united by a common, wheels-within-wheels investment game, which netted $91.8 million from over 200,000 buyers in early December, making Pak by some measures the priciest artist alive).

It’s wrong to say that the “traditional” art world was completely hostile to the trend, since a well-known new-media artist, Kevin McCoy, came up with the NFT idea in the first place, while the centuries-old auction houses Christie’s and Sotheby’s led the charge in popularizing them. What is true is that traditional artists trying to enter the crypto-art space, even artists who’ve worked with digital technologies, have found nowhere near the luck as those viewed as being native creatures of the crypto-art scene, sending critics scrambling to familiarize themselves with a cast of characters with names like XCOPY, Fewocious, Frenetik Void, Hackatao, and SlimeSunday. (A partial exception was Damien Hirst, who understood that the key was not aesthetics but gamified investment—though, nota bene, Hirst’s “The Currency” project has been trending down since its August peak).

Read my series from NFT.NYC for a time capsule. But things are moving fast… We’ll see what this year brings.

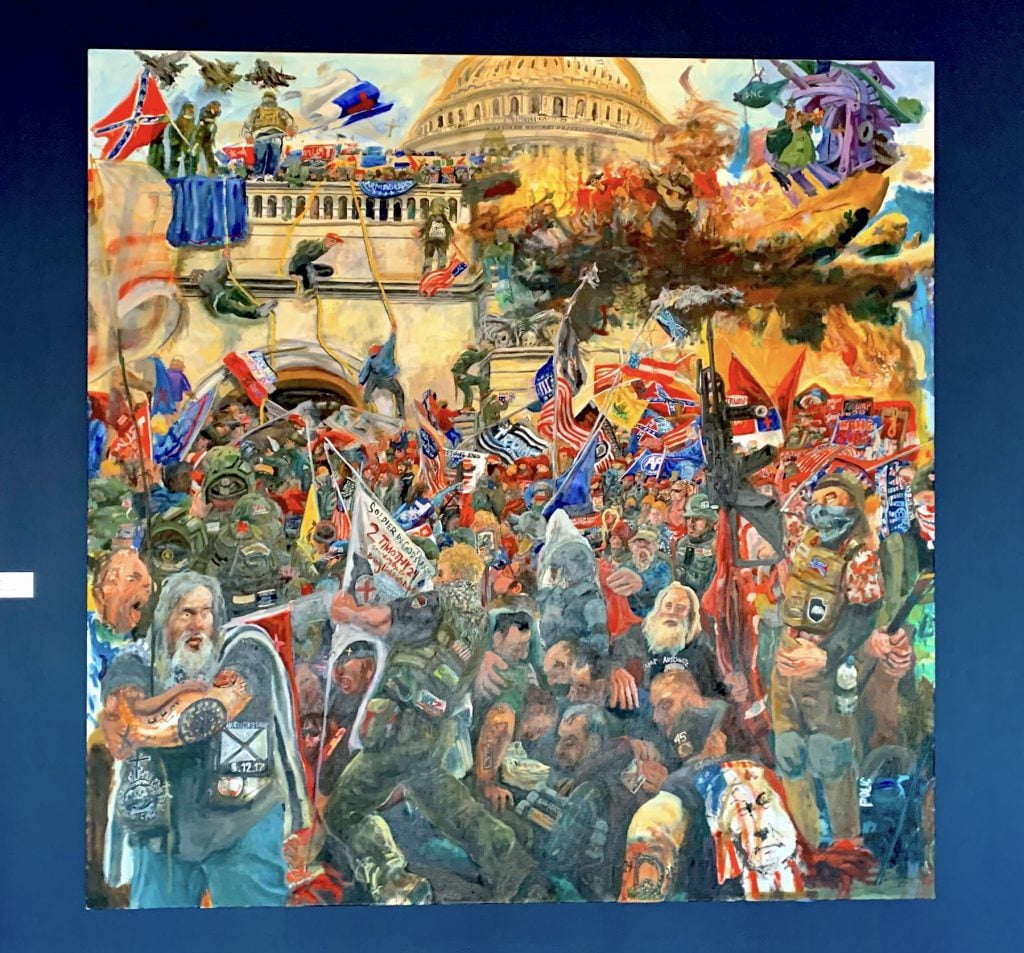

Celeste Dupey-Spencer, Don’t You See That I Am Burning (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

Even as the for-profit immersive art wave promised razzle-dazzle and NFTs built a new pole of attraction shaped around giddy memes, art museums and biennials have gone hard in the other direction, focusing on somber accounting and progressive sentiment. From Celeste Dupey-Spenser’s frenzied nightmare canvas about the January 6 riot (shown with a cycle of other paintings conjuring a sense of U.S.’s dark side at the Prospect New Orleans triennial) to the deserved veneration of Winfred Rembert’s autobiographical works about prison labor, police atrocities, and lynching (both at Fort Gansevoort and in a well-received autobiography, Chasing Me to My Grave), different versions of historical “Reckoning” were the explicit or implicit theme of so much of the art of this past year, in moving ways (though historian Matt Karp’s “History as End,” a thoughtful critique of mainstream liberal culture’s approach to revisiting historical trauma, seems to me more and more to be essential reading as well).

Cover of Time, Feb. 15-22, 2021.

In early 2021, HBO dropped the documentary Black Art: In the Absence of Light, while Time magazine turned its pages over to How to Be an Anti-Racist author Ibram X. Kendi to say we were in a “New Black Renaissance,” offering a list of canonical works from the movement, from the Obama portraits by Kehinde Wiley and Amy Sherald to the Telfar Clemens Shopping Bag. Los Angeles got to work on Destination Crenshaw, a vast public art boulevard dedicated to Black artists. The Metropolitan Museum of Art opened an “Afrofuturist Period Room.” By the time, early last year, that Buzzfeed declared New Black Vanguard author Antwaun Sargent the “art world’s hottest critic,” he had transcended that status entirely by becoming a director at the world’s most powerful gallery, Gagosian. He went on to organize a high-profile show of work by socially engaged Black artists there—and do a cameo on the new Gossip Girl reboot, which itself sought to re-center its image of elite New York society with a Black lead character and a considerably less white ensemble.

French President Emmanuel Macron inspects the Benin bronzes at Quai Branly museum in Paris. © musée du quai Branly – Jacques Chirac, photo Thibaut Chapotot.

The momentum around the restitution of looted colonial artifacts picked up dramatically in 2021. Perhaps the flagship story was that of the Benin Bronzes, with museums across Europe considering—and in some cases, actually executing concrete plans—to return the treasures. In April, Germany announced it would begin returning bronzes from national collections in 2022, while two university museums in the U.K. followed close behind. Washington, D.C.’s National Gallery of Art returned a bronze cockerel in December, around the same time Paris’s Musée du Quai Branly orchestrated the restitution of 26 objects to Nigeria. This movement has touched off exactly the kind of chain reaction you would expect, with each new return raising fresh questions about what else should be given back. Ethiopia received the largest return of treasures in its history from Britain. Calls for the repatriation of other artifacts, for instance those looted from Asia, got louder. U.S. museums were named and shamed in the Pandora Papers for holding looted Cambodian art, and the Denver Museum repatriated four works. Even the quest to return the Parthenon Marbles to Greece started to pick up some steam—Italy announced that it was handing back over a fragment in December. Still, Boris Johnson’s government wasn’t likely to budge in Britain, even after an old article was unearthed showing that the Tory had himself argued they belonged in sunny Greece. How far it will go is a big question in 2022.

MoMA union workers protest at the Museum of Modern Art. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

The museum world had its own version of “Striketober,” the wave of labor unrest that flowed across the nation in the fall, with hard-fought victories at places like John Deere and Kellogg’s. In the museum world, the new union moment was contagious, and transversed the year, with institutions across the country facing union drives, from the Whitney and Hispanic Society in May to the Brooklyn Museum in August to the Baltimore Museum in October. Pandemic-era austerity and dislocation collided with the long-term trend of stagnating conditions, the inspiration-by-example of recent political protest, and the increasingly endemic rejection of the idea that the spiritual rewards of working in culture justify barely livable pay and benefits. Analysts like to talk about the proletarianizing professional classes as being one of the loci of radicalization in our rapidly decaying economic order. The museum staff revolts of 2021 were a case in point. One of the genuine bright spots in a dim year.

Alastair Mckimm, Mario Sorrenti, and Gavin Brown at the debut of Arthur Jafa’s latest film. Photo: Annie Armstrong.

Just about everyone you talk to talks about how alienating and degraded online discourse has become. The idea of the “dark forest” was popularized by writer Caroline Busta, who co-runs the Patreon-powered salon New Models with artist-critics Daniel Keller and Lil Internet. In general, the idea is that the “clearnet,” the part of the internet that is governed by attention algorithms and rewards poorly reasoned instant reaction and/or banal smarm, has been bleached of meaning, while the art world’s inaccessible hierarchies have left it increasingly out of touch with a lot of new energies, causing a self-conscious movement of the smart cultural creators away from these spaces. Ben Smith’s NYT column on the Dimes Square scene as a “shift toward spaces safe from social media” was the big-media, clearest-of-the-clearnet world taking note, even if the cool downtown party kids are just one node of a larger movement of inchoate alt-media energy. While clicks and likes rule the popular imagination more than ever in the AI-perfected attention economy of the TikTok era, it’s also possible that a new kind of cool is being redefined against it.