Still, in 500 years of European colonialism, the one-way flow of cultural and historical objects to Europe (and later North America) was a truly global phenomenon. It has deeply affected many countries around the world, including Asia and the Pacific.

So why have discussions about restitution failed to catch fire in other parts of the world? The answers range from a fear of disrupting diplomatic ties to the absence of legal framework to a desire to take restitution out of the government’s hands and into the people’s via activist collecting. Moving forward, experts say, the conversation will inevitably expand.

Humboldt Forum. Photo: SHF / Hi.Res.Cam. Courtesy Humboldt Forum.

Ransacking the Summer Palace

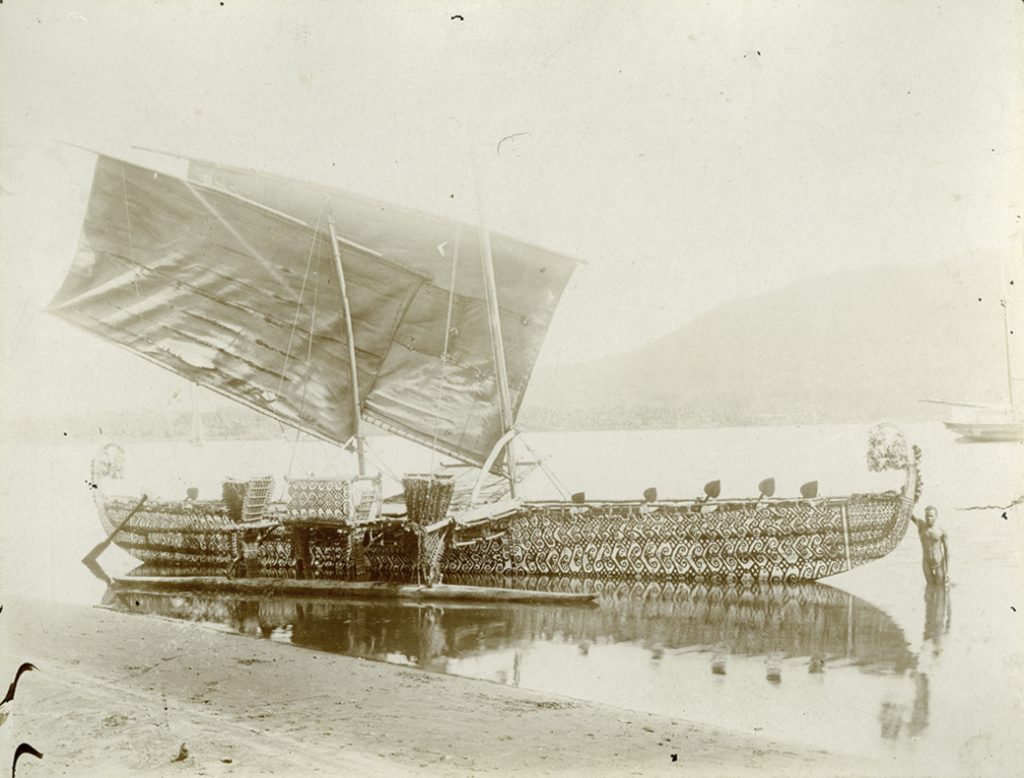

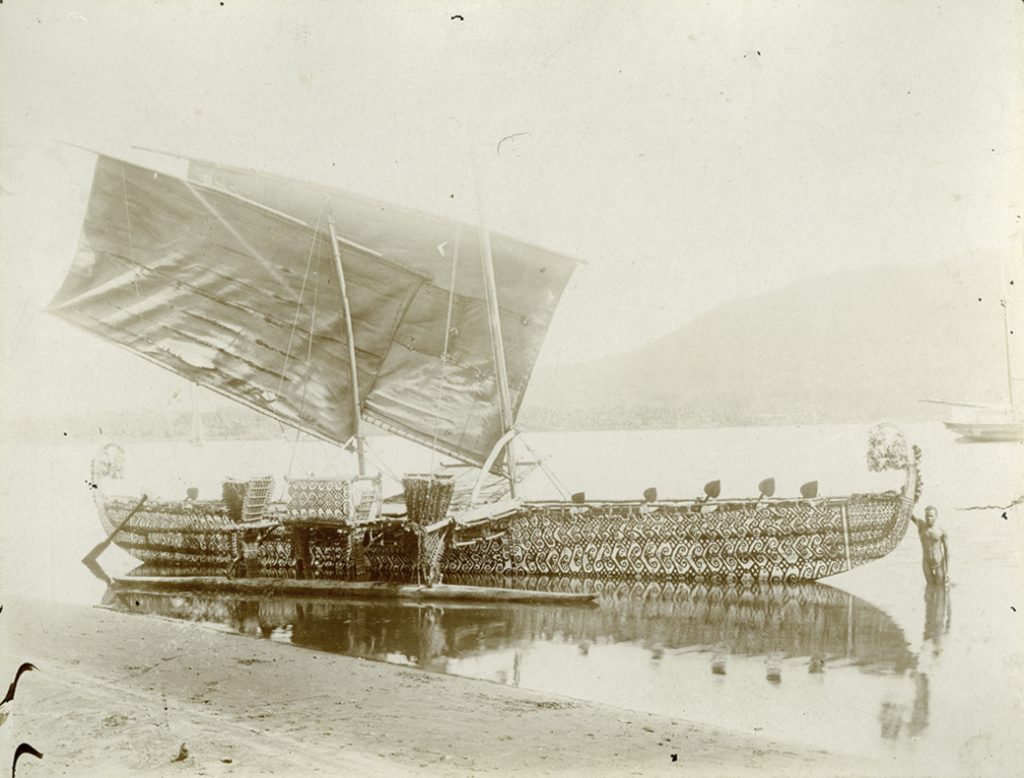

The Prussian Cultural Heritage Foundation, the institution that oversees the Humboldt-Forum and as other public museums, said in a statement to Artnet News that the circumstances surrounding the Luf Boat have been under examination for decades, and that Aly’s published findings do not prove illicit acquisition. Nevertheless, the institution plans to incorporate Aly’s survey into their statement about the boat. It has also reached out to the Papua New Guinea National Museum and Art Gallery for further investigation.

As there are no restitution claims for now, the boat will be exhibited as a “memorial of the horrors of the German colonial era.”

Certainly, it is far from the only object with such a background, nor is Humboldt Forum the only museum to house these disputed collections. The punitive expedition that led to the displacement of the Luf Boat was a common practice among colonial powers in the 19th century, when military retaliation was accompanied by iconoclasm and looting to assert dominance.

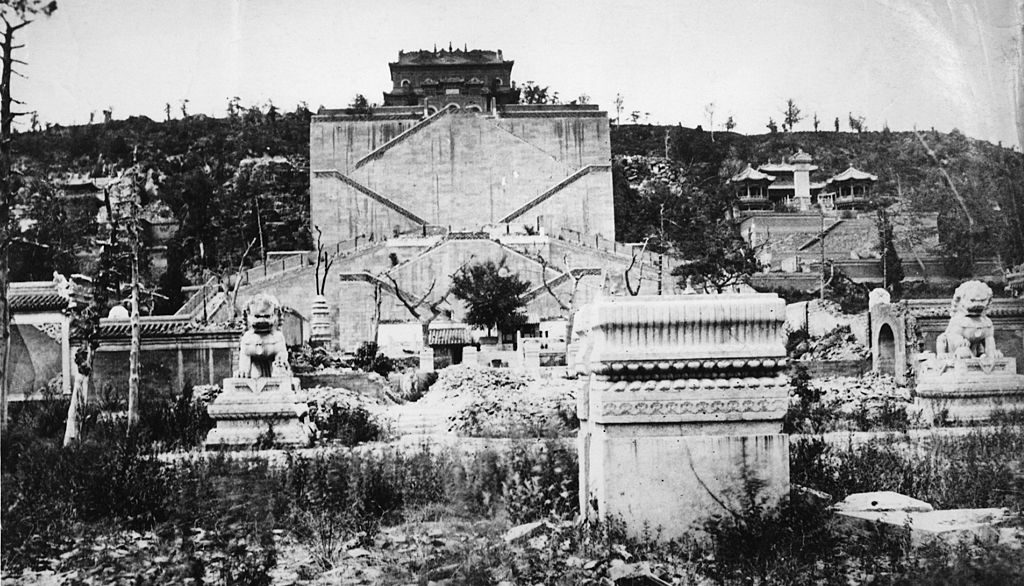

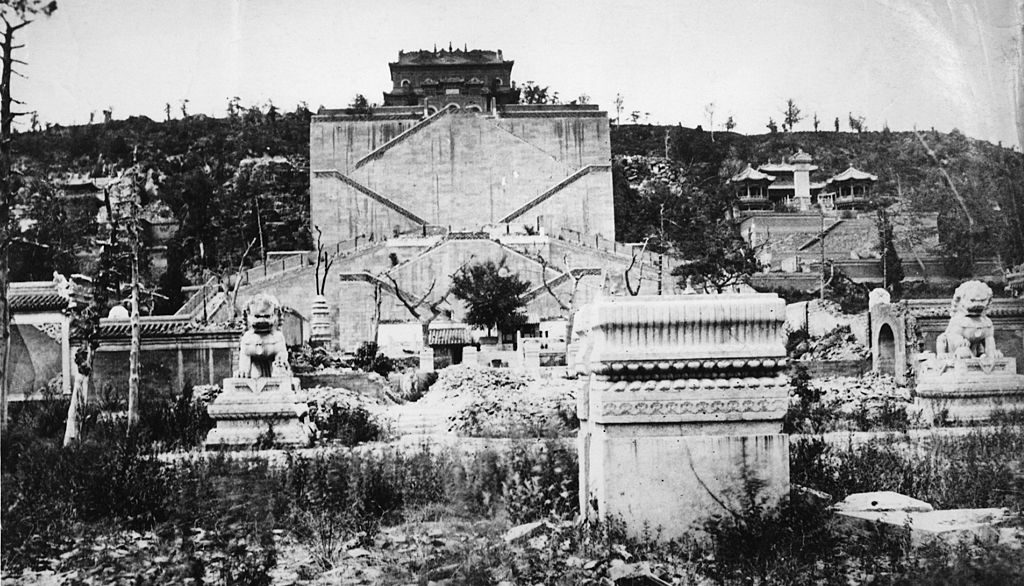

Imperial bronze lion sculptures in the ruins of the Old Summer Palace, Beijing, China, 1869, after its was destroyed by British and French forces during the Second Opium War in 1860. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In Asia, the most notorious event was the ransacking of Yuanming Yuan, Beijing’s Old Summer Palace—it has stirred repatriation discourses for decades. The ransacking by British and French troops at the behest of Lord Elgin during the Second Opium War in 1860 is considered the culmination of what the Chinese call the “century of humiliation,” a period between 1842 and 1945 when the ancient empire crumbled under the pressure of European forces.

Soldiers plundered the most valuable works of art, taking three days to set fire on the vast palace compound. Researchers estimate that up to 1.5 million objects could have been looted or destroyed. The savagery was no secret: a Pekingese dog from the palace gifted to Queen Victoria was named “Looty.”

The (Looted?) Asian Art Market

In recent years, Chinese officials and businessmen started to not just call for the repatriation of antiques, but to take matters into their own hands. Prices for Chinese antiquities have skyrocketed over the past two decades as Chinese collectors went on a buying spree.

The newest record-breaking auction this month fetched a stellar $41.6 million for a Qianlong vase that came into Scottish possession during the “century of humiliation”—it was bought by an Asian collector at Poly Auction in Beijing in June.

Another sale, just last week, set an all-time record in the German market when an Asian collector bought a bronze Ming dynasty sculpture of unspecified provenance for €9.5 million ($11.2 million) at Nagel Auctions in Stuttgart.

Objects from the Old Summer Palace also show up at auction once in a while—in 2018, Chinese authorities tried to stop the sale of a bronze vessel that is known to have been looted from a soldier during the raid. It was sold to an anonymous buyer anyway.

One of the four 18th century Qing dynasty bronze fountainheads, the Monkey, owned by China’s Poly Group are on display at a Beijing museum, in Beijing. Photo credit should read STR/AFP via Getty Images.

The subject of the looting and burning of the Summer Palace has become highly politicized in China and increasingly linked to Chinese nationalism. The state-owned Poly Group established the eponymous Poly Art Museum in Beijing in 1998 to display repatriated artwork. Most of the exhibits on view were bought back by wealthy businessmen at auction, among them the two zodiac heads from the Yves Saint Laurent collection. (The pair were repatriated when collector Cai Mingchao infamously sabotaged the Christie’s auction in 2009 by bidding without ever intending to pay.)

That same year, the Chinese government sent out a “treasure-hunting team” to inspect museums in Europe and the U.S. for Summer Palace objects (many had been taken off display already, both because of growing awareness about brutality of the ransacking and because of the concerns about the authenticity of the “Summer Palace” label—many objects have been misattributed). No restitution claims materialized.

A series of high-profile art heists targeting treasured Chinese objects began to crop up: Among the robbed were the Chinese Pavilion at Drottningholm Palace in Sweden in 2010; the Château de Fontainebleau in France, home to Empress Eugénie’s Summer Palace collection, in 2015; and the KODE Museum in Norway in 2013 and 2018. A GQ feature in 2018 speculated that the heists could be linked to the government-owned Poly Group.

Visitors watch a bronze statue of a horse’s head exhibited at the Zhengjue Temple in the Old Summer Palace (Yuanmingyuan). Photo by Chen Xiaogen/VCG via Getty Images)

Restitution

The ongoing issue of the Old Summer Palace is just the tip of the iceberg—palaces from all over Asia and up to the Middle East (not to mention the rest of the world) were looted by European troops.

In 1812, Sir Raffles sacked the Palace of Yogyakarta; in 1885, British troops looted the Mandalay Palace; that same year, French troops took wagons full of antiques from the Imperial Palace of Hue (the already-defunct 11th century Imperial City of Thang Long was destroyed by the French during the same period). The Dutch looted the Lombok Palace in 1894, and the 1903 Younghusband expedition to Tibet effectively created the collections of Tibetan art in most British museums—just to name a few.

In the fight for restitution, Myanmar, Indonesia, and Cambodia have been particularly outspoken, and the latter nation has been particularly successful in its quest for restoring lost Khmer heritage. Earlier this year, deceased art dealer and smuggler Douglas Latchford’s daughter announced she would return 125 Khmer sculptures worth $50 million from her father’s collection.

But that’s not always the case—the situation of Vietnam, which was under colonial rule as French Indochina, poses a stark contrast. Troves of Vietnamese antiques are located in France. The Musée Guimet houses part of the Imperial Treasure taken to France in 1885, a formidable collection of Bronze Age Dong Son drums and myriad sculptures from the ancient kingdom of Champa.

While media outlets and curators have raised the matter of repatriation, and some Vietnamese collectors have started to repatriate antiques by way of auctions, the Vietnamese government has remained silent. One of the reasons is that it does not have any national legal framework to handle potential restitutions.

“The French were the ruling power and they saw themselves rightfully entitled to the territories and possessions at the time,” Huynh Thi Anh Van, director of the Hue Museum of Royal Antiquities, told Artnet News. “Because of the obscurity surrounding the documentation and provenance of artwork, the outcome for a successful restitution campaign is very uncertain. The legal paths to claim restitutions of artwork removed under colonial rule are very complicated and expensive.”

She said the Vietnamese government may want to avoid jeopardizing diplomatic relations; as such, many restitutions are initiated by the countries which now own the works, not the source nations.

© Ethnologisches Museum der Staatlichen Museen zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz / Richard Parkinson

Reconciliation

The majority of the collection of the he Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Asian Art in Berlin, where the Luf Boat is held, is in storage, and, according to Prussian Cultural Foundation, no claims from Asia or Latin America have been made at the time of writing. The foundation stated that it began to reach out to institutions in the countries of origin for research on objects in their collections several years ago.

The discussion around the Luf Boat in Berlin, in a museum where restitution has become a focal point due to public pressure, may set a precedent for the colonial restitution debate to truly set sail beyond Africa. At the same time, the exquisite object is just one among tens of thousands in the Ethnological Museum of Berlin: this summer, the Berlin daily Tagesspiegel questioned the rightful acquisition of another highlight, murals from Silk Road caves that are soon to be exhibited at Humboldt Forum.

Adalbert Gail, a retired professor of South Asian art who was responsible for those murals in the 1970s, told Artnet News that the conversation has changed dramatically. “As a young curator, I had the feeling that the circumstances under which they got here can’t be rightful,” he said. “But voicing any critique at the time would have meant ending my career.” He emphasized that it is the responsibility of institutions like the Humboldt Forum to research the colonial heritage and be transparent about the plunder that might have surrounded their acquisition. “What they are doing now is not enough,” he said.

Indeed, when you look at the ratio, its clear that there is an uphill battle ahead. The Ethnological Museum and the Museum of Asian Art hired four restitution experts to look into the colonial past of nearly 500,000 objects for the first time in 2019. Each one may require individual investigation to reconstruct its path to Europe.

“The issue is clear for me,” said Panggah Ardiyansyah, a scholar focused on Southeast Asia and restitution. “Just return objects that were illicitly removed and help with technical support and conservation. You can’t rectify the past, but that’s the least you can do for some justice. It’s for the future.”