We got to know our workers and their families. Mostly I would drive into town alone to meet the men. After work they dressed up and gathered in the center of town where they strutted about laughing and smoking, walking arm-in-arm and sometimes dancing with each other. Oddly, no women, who mostly stayed at home, were allowed to dance with the men. Unlike the dandified men the women dressed shabbily usually in black. It was hard to get to know them but Nancy finally got some insight into their lives.

We were invited to a “Batsman,” a Baptism, in the home of one of my workers. The event began stiffly, the men as usual gathered together in one corner, the women, many with small children, hung back at first, whispering and tittering, and then they surged forward and pressed pastries on us. Gradually they loosened up, talking to Nancy about the baby and patting her tummy for good luck, a local custom. They admired her appearance, saying they knew from magazines and from families who had immigrated to Brooklyn about makeup and pretty clothes and how to take care of themselves but knew they couldn’t afford such things.

It became clear these women handled the economics of their families, not the men. Any money the men earned went straight to the women. Men proudly viewed babies as a sign of their masculinity but the women knew their true cost. That’s why, they confessed, they were happy the “casingh”’ or whorehouse in nearby Piazza Armerina hadn’t been closed down. Visits there were cheaper than the babies they’d otherwise have. We agreed if changes were to come to Sicilian social attitudes, they would come from the women. The night ended merrily with many of the women as well as the men escorting us, laughing all the way down to our car.

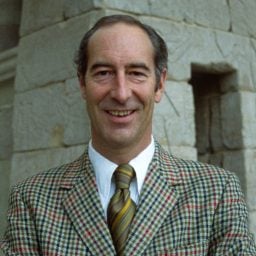

The man I’d grown most attached to in my crew, Filippo Sufia, took off. Twenty-seven, he looked forty with dark hair already turning gray. Slight and stooped in stature, he had a thin face and delicate features which belied the ease with which he wielded the heavy pick. His lively eyes were his only youthful features. There was humor there, but also a sadness and a humility, which could be mistaken for melancholy. When he was confused or didn’t understand what you were saying, he’d cock his head sharply to the side and narrow his eyes, trying to look pensive, but appearing sly.

Unable to keep his family on our seasonal pay, he was leaving the dig to work in the mines of France and Belgium. He wanted to meet me in the village for the last time. We met in the piazza and had a café and a sweet roll, one of those hard, granular cakes, which left an acrid taste in my mouth. As we walked to the house where we’d make our farewells over a game of Briscola, the local version of Bridge, he explained it was not his house — his was too poor for the “Dottore” — but the house of his friend, Calcagno.

He was pre-occupied about his forthcoming trip to France — he’d only once been out of the province of Enna. And he was worried about the contract he’d have to sign in Milan. He was not sure that the document would make him work below the earth, though they had promised him a sorting job, away from the pits.

The June night was chilly and the deep fog only reflected his mood as we climbed the hill. He became more cheerful when we reached Calcano’s house where we joined his friends for the game. The evening became very merry with many toasts to me and good luck wishes to Filippo.

When the time came to leave it was even colder and the fog had turned to rain. Filippo slipped his arm under mine and we made our way to the Piazza. We stood there by my car, shivering in the fog, silent in the embarrassment of having nothing left to say.

“Filippo, there’ll be a great lack without you. You have been an expert, the best among the entire crew,” I said.

Filippo responded with great feeling, “Dottore, I will love you forever. You have been good to me. You have not been ‘superbo’, haughty. You do not mind us workers; you do not mind our poor houses. I thought at first that you’d be distant from us. At first you did not speak.”

“I was scared,” I laughed.

“But you wanted to learn Aidonese and you did. Now I must leave. Saturday I go to France and then someday to Canada and maybe America, Nuova York, where you live. I have a cousin in Brooklyn.”

“Filippo, I have something for you to remember me by, a good luck token. Look at these two coins. I bought them in Agrigento. They are ancient Greek like the ones we found in the trenches. I would like you to have one to carry with you. I’ll have the other. When you touch yours think of me and I will think of you safe in France or Belgium when I touch mine.”

“Dottore, thank you. This is a part of your heart you are giving me and I will always hold it and think of you. I have something for you too. It is nothing, a vicette, a shard of remembrance. A picture of me.”

The photograph was for a passport, oval and grainy, cut out with ragged edges and printed on heavy paper grained by a honeycomb, which pocked Filippo’s face. He sat stiffly, holding his breath, looking fearfully slightly away from the lens. His moustache, broken into two unequal triangles by the center hollow of his lip hung above the thin line of his mouth which was open slightly and added to the overall look of anxiety. The eyes were confused and sad.

On the back of the picture, written laboriously, barely legible, was the inscription, “With love, I offer this poor remembrance. His worker, Filippo Sufia. Remember him.”

“Grazie, buon’ amico,'” I said.

“Tant’ bell’ cos’, Dottore.” We embraced and he kissed my cheeks. “Please drive carefully, Dottore.”

“Ci vediamo, Filippo, we’ll see each other again, for sure.”

I drove off and my lights bathed the tiny piazza and cast shimmering silhouettes of stunted almond trees against the buildings. The last glimmer showed me a small man, hunched over, his arm raised in a wave.

On his way to France he wrote several postcards — from Rome, Milan and Belgium. I wrote him a fond letter telling him the latest at the trench, making a site drawing of what we’d done and assuring him he was one of the finest in the team. “Best of luck,” I wrote, “and don’t forget to touch that remembrance of mine when you feel the need.” I got no reply and figured I’d never hear from him or see him again.

Eleven years later, in 1968, my secretary at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Cecilia Mescall, came into my office — I was having a sandwich at my desk. She had a puzzled smile on her face.

“There’s a strange guy out here, speaks nothing we can figure, keeps kneading his hat. Something like ‘Dottre.’ And he asked me to give you this. It’s pretty.”

There was the silver coin. I was stunned and rushed out my door.

We embraced. He told me his story in Aidonese and in passable French. He had been able to make a deal in Belgium, worked above ground at a coal mine, and in six months had gone to Canada where he’d been working in a variety of jobs. He laughingly recounted that he had just slithered down the anchor chain of a tramp steamer in Brooklyn that morning and wanted my help. He had found his cousin in Brooklyn and was hiding with him.

It took several months for Filippo to learn English and for the museum to get him working papers and eventually a citizenship (there was a delightfully corrupt Brooklyn congressman named Mario Biaggi who pulled off the deal).

We hired Filippo as a guard because I knew he’d be the best one on the roster, knowing that he knew that I knew how he had arrived. In time he became the superintendent of all guards. It was Filippo who persuaded me to start hiring women.

“Filippo, you of all people, you from Aidone where men and women still cannot dance together publicly; you are suggesting female guards!”

“You, of all people, Dottore, who does so many new things for the museum must know this place must change with the times. Besides, women have delicate hands.”

The most amazing Aidone experience came at Easter time when the whole town, men, women and children all turned out for two festivals, one which was profoundly moving and the other an antic, slapstick performance.

On Good Friday we young diggers spent all night on the streets of Aidone watching and photographing one of the most uncanny ceremonies I had ever seen, Christ’s funeral procession. It started in the church of Sant’ Anna at the foot of the wooden Crucifix painted a pale yellow, carved by Fra Umile da Petralia, when no one knew, but I pegged it from style as late 17th century. The sculpture was provincial but the arms and legs were cleverly pegged and could be moved. I had heard of articulated figures of Christ; they were exceedingly rare and I had never seen one before.

The interior of Sant’ Anna was brightly lighted and every inch of the place was filled with men in cloaks of thick midnight blue felt and the women in black shawls. The children held tightly by their parents for once didn’t utter a sound.

For two hours the priest told the story of the Passion and Crucifixion, detailing the suffering of Christ and it was chilling. He spoke about the emotions of those who had witnessed the crucifixion. His language was florid, his gestures dramatic. The crowd listened raptly to every word. This priest was beloved in the village and in the surrounding communities, for he was sympathetic to the poor and was not, my men told me,the typical Catholic priest who took money from the poor; he kept the poor parish alive, even making donations from his meager salary.

At ten o’clock, the priest spread his arms apart in the gesture of the crucified Christ and a group of attendants, dressed in white shrouds and hoods came forward and very slowly removed the yellow body of Christ from the cross. This was accompanied by chants I couldn’t understand. Reverentially the arms were moved down to the figure’s sides — with more tenderness than on any living human being. It took half an hour.

The throng became utterly silent as the body of Christ, for by now to them it had become a real corpse, was removed from the cross and transported to the nave of the church. It was placed into a glass coffin.

The procession illuminated by dozens of torches burning on long poles started from the church and wended its way through the narrow streets at a snail’s pace. The coffin was bedecked with flowers and inside were lamps, which illuminated the body of Christ as well as the path through the narrow alleys.

The sounds were weird. A single snare drum at the head of the column of penitents would sound every thirty seconds. The women ululated like Arabs. At times the marchers would fall into a trance and there’d be silence until one of the party raised his hands to his mouth and sent out a long, wailing cry into the darkness. The torches and candles would cast a flickering light on the onlookers gathered on each side of the narrow path and then, like a blazing sun in comparison, the glass coffin would follow and the darkened faces which seemed ominous and threatening would become human again.

The bier was carried through every single street in Aidone. It took from ten at night until past three in the morning for every street and house to be visited, the inhabitants all coming forward to genuflect and pray and wail in profound sadness.

The festival on Easter Sunday was so different, full of gaiety, even frivolity. The twelve Apostles were represented by huge papier-mâché bodies and masks, three meters high, garishly painted, topped by masses of cheap silk fabrics. All had grotesque black, staring eyes with silly grins slapped on their ugly faces. Their cheeks were stained vermilion and their hair a greenish, slippery black. They had a cruel, embalmed look about them. In their claw-like hands each held a bunch of flowers. Each man supported what looked to me like a hundred pounds of puppetry.

Peter, a gigantic creature with eyes that looked as if he’d lost a very tough fight, began the play, or game. He skipped off to all the cafes in town looking for Mary to tell her that Christ had risen. Why he chose the cafes was not logically explained as women here rarely frequented cafes. However, he managed to fill up with drinks, coffee and cigarettes and thus loved his task.

A bit later the other Saints, each one a different grotesquery, emerged from a Church high on the hill and with the statue of Christ carried in procession wound down around the town accompanied by a brass band until at last they came to the main Piazza. There the Saints, one by one, detached themselves from the group and entered the Church to tell Mary of the Resurrection. She, not willing to believe just any Apostle, insisted that Peter in person give her the word. The saints frantically searched for and kept dashing back to the church trying to convince the recalcitrant Mary. Peter was hard to locate because he was hanging around the Piazza cadging cigarettes and drinks making the occasional sally between buildings to change the poor guy holding the huge effigy or to go to the bathroom.

After nearly two hours of this crazed activity, Peter was produced, Mary was convinced. She was led out of her church in one procession by figures covered in white sheets and with masks over their faces resembling members of the Ku Klux Klan. The Virgin was draped in black. The other procession with the figure of Christ now bedecked with flowers which had been just out of sight of the Piazza moved forward. As the two processions came together a string was pulled and the black fell from Mary’s robe revealing her in a stunning blue and gold cloak. The two litters were dipped and the two figures bowed to each other in greeting.

The crowd roared and the band played on.

Previous Chapter – Next Chapter