Just when we were getting excited about going to Sicily to the dig at Serra Orlando, Erik Sjöqvist and his wife Gurli came to town in early February 1957. He didn’t sound very friendly over the phone and asked if I had my heart set on coming to the dig.

“It’s me they don’t want,” Nancy said. “Let’s invite them over for dinner here and have it out.”

She thought Sjöqvist had gotten the impression at Princeton that she was too chic and too fashionably coiffed for the rigors of an excavation in the wilds of Sicily.

But after a tour of our flat and when they’d heard that we’d lived happily for months without heat or hot water, Erik said, “Frankly, Gurli and I were apprehensive that you, Nancy, not Tom who I know was a Marine, but you, might be put off by the primitive conditions that you’ll encounter on the dig. No hot water and arising with the sun. . . .”

Despite his warning, Nancy was actually looking forward to the adventure and told him so enthusiastically.

“Good for you. This will be a fine season, I can feel it in my old bones,” Sjöqvist said.

“How did you find the place?” I asked. “How did you know you’d find ancient remains?”

“Well, it didn’t reveal itself after a bombing like Palestrina, but the Air Force did have a role,” Sjöqvist explained. “Ancient historians mentioned certain inland posts. And we obtained World War II Air Force photos and Italian military infrared photos of the area. An ancient city was clearly visible with traces of ancient roads. My colleague and I figured that an inland site might be richer in discoveries than the more famous but heavily worked coastal sites such as Agrigento or Selinunte. Plus we thought the Italian authorities would be in favor, since the coastal areas are thought to be more important than inland sites. We went to Serra Orlando and spent a week there. Using the aerial photos as maps, we traced the entire ancient wall on foot. From the extent of the walls we could guess the importance and wealth of the unknown city. Almost nothing was to be seen on the ground. That’s normal for Sicily, being an earthquake region. The bits and pieces we did find on the surface — coins and especially potsherds, the echor of archaeologists — were of high quality. We found, to our delight, large amounts of Attic black glaze, which is the best of the best. We also visited farmhouses near the site and the houses in Aidone, seeking antique remains used over the centuries for building material. We found lots. Some were carved and thus we could date them. On the basis of all this, we decided to go ahead. And now, both of you will be a part of this undertaking. Congratulations!”

Nancy and I took off in late February through Naples, Ravello and Messina.

We spent four days devouring Naples, its museums, its famed archaeological sites and its great restaurants — after one seafood meal I almost died and was stuck in a tiny room of our hotel for four days, sweating out the food poisoning. During my illness someone stripped our Renault of its tires and my USA plate. Bella Napoli! The National Museum was sublime, especially the finds from Herculaneum and Pompeii. My impression of the quality of Roman bronzes from the stunning statues discovered at both sites was highly favorable. I had been taught — erroneously — that Roman bronzes were pale compared to Greek ones. But, to me, the Roman sculptures were equal to the finest Greek ones. I noted with special interest the trove of Roman copies of Greek original marbles from the Farnese Collection that used to be displayed in niches in the Camera Farnese frescoed by Annibale Carracci. On my return to Princeton I had to prepare a seminar paper on those frescoes and their antique models and had studied the paintings in Rome with my usual fixed intensity.

What got us about Pompeii was its feeling of life. It felt as if everybody had just left town the day before and would soon return. Pots seemed left still bubbling on stoves. Open wine jugs stood on the tables. There was bread on the tables. Doors were open. Beds unmade. There was a casual human untidiness all around. We found the graffiti compellingly alive. “Hello Julius.” “Gratius loves Helena.” “The Hell with Cato.” “Vespasian is an ass.”

We were fascinated by the presence of death, too. Ten percent never got the word that a catastrophe was in the works. When the first digger found recesses in the ash he injected plaster, which preserved the three-dimensional outlines of the fallen human bodies. We saw two ghostly white gentlemen in a public bath, twisted in the agony of asphyxiation. Leave? Hell no! We paid for the towels and anyway, had only just gotten through the frigidarium.

We decided to drive counter-clockwise around Sicily before going to the hamlet of Aidone where the excavation was located. From the ferry at Messina we’d drive up to Cefalu and Tindari, where there were swell ancient Greek remains, then Palermo, Erice, Trapani, Noto, Siracusa, Catania and on to Aidone.

At Solunto I was panting to visit a Greek temple of the archaic period.

“Where are these ruins?” Nancy asked.

“Way up there on Mount Catalfamo.”

“How do we get there; I don’t see a road,” my wife asked.

“By one of these little donkeys for hire here.”

“Count me out.” Nancy said. “They look too rough.”

As soon as she’d said it, I suspected she was pregnant. I didn’t say a word, thinking it would be better for her to tell me when she wanted.

We’d learned from the ACI guidebook that in Catelvetrano there was a “not-to-be-missed” early 5th century Greek bronze, a small and perfect kouros or sacred youth. We arrived and asked for the museum. It was not in a museum but in a drawer in the mayor’s desk. We went to City Hall and his honor pulled this eight-inch-tall statue out and put it on his desk as he chattered away on the phone. He motioned for us to take it in our hands and we did, stunned by its beauty. I memorized every inch of the treasure.

“Doesn’t this make our list of things to steal?” Nancy whispered.

“For certain. Maybe I can just slip it into my pocket while he’s busy on the phone.”

“Or, give the mayor a big tip. I have never seen a more beautiful guy — except his prick seems small.”

“Hold him a little while longer.”

Later I was to learn that all ancient Greek kouroi have small pricks. Partly because of my concentrated examination of this kouros, I was able many years later to quickly spot a fake marble kouros in a wealthy American museum.

At Selinunte we found what seemed to be a dozen Greek temples, most of which looked as if a giant hand from heaven had come down and flicked the buildings asunder.

Nancy squeezed my arm in alarm. “Two guys are following us.”

They approached, eyes darting around suspiciously. Abruptly one guy thrust into my face a six-inch high-seated terracotta votive figure I dated to the 6th century B.C. When I took it in hand it was so heavy I almost dropped it. I started laughing, for it was a solid bronze cast painted to look like terracotta. I managed to get the guy to admit that, yes, he had the original 6th century B.C. terracotta mold — exceedingly rare! But he wouldn’t sell it because how would he make more like this?

He had two silver coins with Nero’s head in deep relief and I bought them instead. I wanted to make them into earrings for Nancy but she laughed and said, “That monster on my ears? Hell, no.” So, I kept them for myself.

It was in the old city in Siracusa at a peaceful dinner across from the enchanting Cathedral when my wife kissed me and said, “Tommy, I think I might be pregnant.”

I had been right! I was full of joy and relieved; there had been times when the awful thought crossed my mind that after the miscarriage we might never have children. This was one of the happiest moments of our lives. But I was also frightened. Would it happen again? My God, pregnant in the wilds of Sicily!

From that moment on I restated to myself my wedding vows. I vowed to love her, protect her, nurture her and take care of her in every way. Sure, I knew there’d be arguments, fights, possibly even estrangements. We were both maturing at differing speeds. But, come what may, I would stand fast for my lovely, intelligent and supremely hit-the-nail-on-the-head wife.

The drive from Catania to Aidone was gently uphill through parched countryside. Nancy read the guide: “Aidone is an agricultural town — almonds and various other nuts — half a mile above sea level in the Monti Erei range. Enna is twenty-five miles to the North and Piazza Armerina is twelve miles to the West. Population is under 2,000. There’s the Church of Sant’Anna inside, which has a wooden crucifix, carved by one Fra Umile da Petralia, date unknown. Aidone is known as ’the balcony of Sicily’ since from its height you can see Mount Aetna, the Catania plain, and, sometimes, as far as Syracuse and the Ionian Sea. The name of the town comes from the Arab ‘Ay-ndun’ meaning ’higher water spring’. The Normans founded it, it’s likely, on an unnamed Arab settlement. The Normans came to Sicily under Roger to destroy the Muslims. In the following century Aidone passed through many different dominions: the Swabians, Aragonese, Castilians, and finally the Bourbons from 1700 to 1860. Followed by the Hovings in 1957,” she ad libbed.

For a mile between Serra Orlando and Aidone the road was jagged rock fill. We had to drive slowly over each rock with the tires moaning ominously. We could only think of Nancy’s condition and having four simultaneous flats.

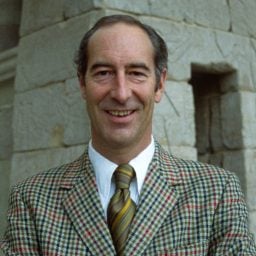

We arrived safely at the meeting place, a hotel in Piazza Armerina and met the team. It consisted of Erik and Gurli Sjöqvist, Chuck Williams, the draughtsman and architect, Lucy Shoe, the cataloguer, our friend Fred Licht, the photographer Pal Nils Nillson and his beautiful wife Ingeyard and Kyle Roberts, a Princeton undergraduate student. There was also Helen Woodruff, an archaeology buff from Princeton and a friend of the Sjöqvists. Woodruff was to be the foreman of the overall works including the dumps. Keeping track of dumps in archaeology was vital because the earth we diggers churned up had to go somewhere known definitively to be outside the excavated area.

Woodruff briefed us on the regimen at the Villa Ranphalli, a rambling summerhouse rented to us by a Sicilian living in Milan. “We’ll live by the sun since there’s no electricity. Rise when you want, but breakfast in the common room — it has a large table — is at 6:30 sharp. You’ll arrive at the site at 7:00. Lunch is normally there. Our cook, Dino, will prepare sandwiches. You’ll have to make your own mattresses — the fresh straw will be in bags in the rooms as well as sheep wool for the pillows.”

That evening Nancy and I exchanged our first impressions of the crew.

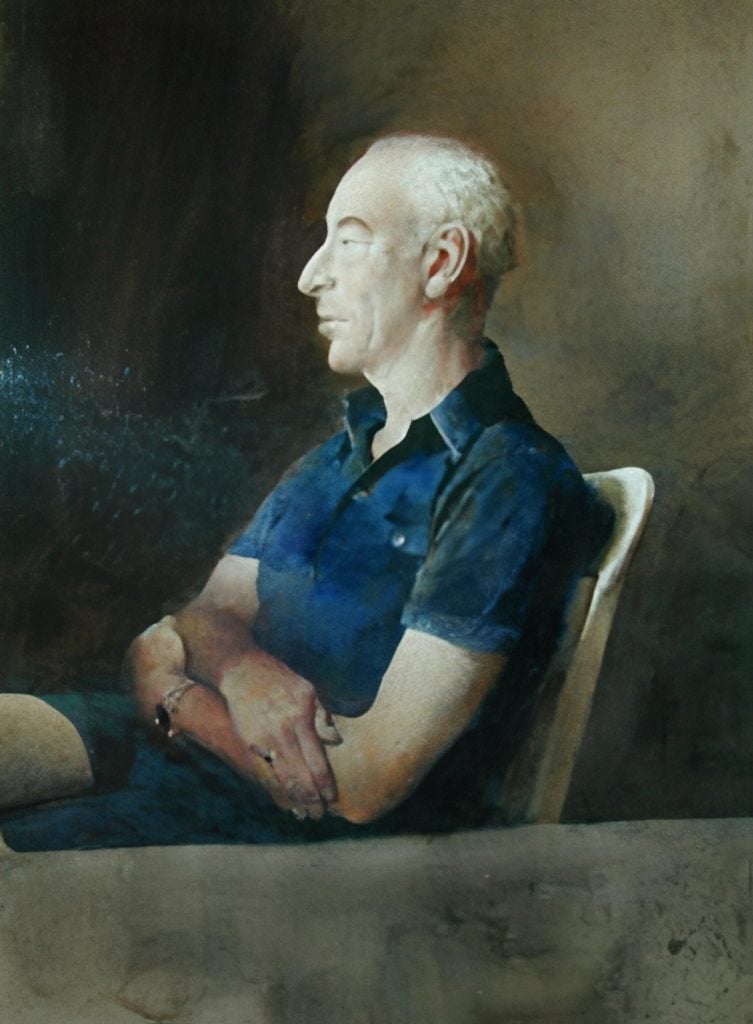

“Erik looks so wan,” my wife observed. “I was told that his ear is very painful but that he refuses to go to a doctor in Catania, he’s so eager to get the ball rolling. I wonder if he’ll make it through.”

“He’s a Swede, so he will. I wonder if his friend, the King of Sweden, will appear — he did last season and found something gripping but I can’t remember what.”

“If he shows you can offer his Highness one of Enzo’s gold-tipped Murattis — ‘as smoked by the Royalty and Nobility.” He never did show.

“Chuck Williams seems competent and we’ll need a good measurer and draughtsman.”

“He’s so uptight,” my wife grumbled

“As is this Kyle Roberts,” I said. I was furious that a mere undergraduate had been invited — I supposed to fill in for me if we had been kissed off. “Typical endomorph, crew-cut athletic type. He seems so uneasy and almost too polite and can’t look anyone directly in the eye. Our dear Fred Steven Licht hasn’t changed. Marvelous outfit! Black everything from beret to boots except for that red five-foot-long scarf. That’s new. Remember the story he told us of how he got into art history?”

His very rich, very social Swiss watch-making family had badgered him to follow in the business, which bored him to tears. He had been sent to South America to learn the business and in six months sales had soared. He had created a new watch face, which had the image of Jesus Christ on it with a little red heart that actually pumped every second. After this financial triumph he implored his family to let him study art history. No. He had to become a doctor, but he washed out, hating the sight of blood. Only then was he allowed to study art history and he received his Ph.D. from Basel University at a young age.

Nancy asked me, “What’s your take on Lucy T. Shoe? I have been assigned to help her cataloging the finds.”

“She’s the librarian at Princeton’s Institute for Advanced Studies. She specializes in the dating of ancient Greek architectural fragments. With a template she measures the profile of some architectural fragment and can tell you the date to the time of day.”

“How thrilling.”

“Her cataloging will be vital — if she does it punctiliously the dig will succeed, if things get screwed up, it’ll fail.”

“I hope I won’t screw up,” she whispered. “I know her type, prim, slightly pickled ’feminine’ woman who can get bitchy. I’m not sure if I can live with this Shoe for more than twenty days, not to say for months. As for Helen she’s talkative, jocular and amusing and I like her. She may become my surrogate mother.”

“The Nilssons?”

“Who knows? They spoke only Swedish the whole dinner. She’s the kind of pretty thing you go for, so watch it.”

Our room in the Villa Ranphalli was cell-like but had a large window. We’d have to slip through the Nilsson’s room to get to the common room and the dining area. There was one inside toilet, but it didn’t flush. A couple of buckets were there to pour into it. Off to the west there were a series of rooms for the daily finds, the shard boxes and a lab with a huge glass receptacle filled with hydrochloric acid to give a quick clean to the muddy finds. Erik handled that dangerous task.

The first meal at the Villa was great — Dino did have a touch. After the meal Erik gave us trench masters an hour-long lecture on how to make a proper trench and how to handle the notebooks, the diaries and the entries of finds into the catalog.

The next morning we drove with Professor Erik to the site which seemed to me a scrubby arena about the size of two football fields with the Cittadella or Acropolis looming on the east side about five hundred feet up. There were the remains of polygonal stairs found at the end of the previous season and dozens of rubble walls and lots of clay. It sure didn’t look like Agrigento. I was let down.

Erik gave us our assignments. I was to be placed west of the large open space, the meeting place in ancient Greece called the Agora. My job was to follow up and link a bunch of fragmentary ancient drainpipes. Drainpipes? That really depressed me.

A trench measured fifteen by twenty five feet and its dimensions were laid out on the surface with four stakes and white twine. The workers started to dig with large picks and then used smaller ones and, eventually to trowels and spatulas. You peeled back the soil a foot down at a time and after that by inches as ancient pieces began to appear. My job was to describe and locate any finds on a drawing of the trench I made in my notebook. I was to watch the color changes of the side of the trench. The color would start off black, then change to brown, then yellow, then orange, and finally deep-chocolate brown, the bed clay of the area some twelve feet down. The colors roughly designated the centuries back in time.

At the side of the trench were stacked numbers of flat wooden boxes for the potsherds. The shards were assorted into types — jug necks, jug bodies and bottoms. Exceptional finds were placed in batting in other flat boxes. Roof tiles were stacked at the side of the trench.

I was slightly overwhelmed and very nervous. I was expected to keep accurate scale drawings of the trenches in my graph-paper notebooks. I had to make detailed drawings of any finds. Coins had to be given an on-the-spot written description along with a drawing that would make Leonardo da Vinci envious. The exact location of each discovery had to be annotated in the notebook with specific three-dimensional measurements.

God, I thought, I’d be out there on my own working in two trenches with seven workers, all shoveling away, finding one ancient artifact after another, with me dashing around in the mud measuring, drawing, describing, annotating. I was flabbergasted that there wasn’t a more modern way of doing it — photographs and accurate grids and the like. No such thing. The old way was the only way. Erik assured me that the pace would be slow and steady and that I’d have ample time to juggle my duties. In his long digging career he had never found an area where the finds were so profuse that the cataloging and recording could not easily be done. As it would turn out, what I eventually found made the job all but impossible to carry out.

I expressed my fears to Nancy that evening, as we lay on our straw mattresses in the sputtering light of the gas lantern while I had a final slam of cognac and a smoke. “I just hope I don’t fuck up.”

“Spoken like a true Marine. You’ll find historic things, I know it.”

And I did, the very first day. It was raining hard with gusty winds making the temperature plunge to the mid-forties. I met my foreman, Don Ciccio, a wan and thin spider of a man, carrying under his arm his little black and white terrier, Fiorino. Under him were six workers.

The morning’s work involved removing the remaining traces of the previous season’s dump and digging down one foot into fresh soil. We found two mud-caked coins of unknown date and I carefully measured their precise location in the trench and how far down into the soil they were, drawing them as best I could in the notebook and entering descriptions of their size into my book. I took a half hour to do it in the cold since I wanted to be exact.

“I was petrified,” I told Nancy later, “thinking I’d drop the notebook in the mud and rain. My fingers were freezing and I could barely write, all the time thinking that the workmen were thinking I was an idiot.”

It rained so hard that we had to suspend digging around midday. I returned to my trench in the afternoon when the pelting rains subsided and found the thing. It was about two feet down in the fresh earth at the far right end of the rectangular pit. Giovanni, a sharp-eyed giant of a man with a neck as wide as his massive head, indicated a find. It appeared to be a loop heavily caked with mud. Jesus, a necklace? Calming myself down, I diligently made all the necessary catalog entries, wrapped it in batting and personally carried it down to the laboratory where Erik Sjöqvist was working at the acid bath.

He was dressed in a rubber smock with rubber gauntlets up to his armpits to shield him from any acid spatters. He took my discovery, turned around, thrust it into the acid for a couple of seconds to allow the caked mud to boil off.

“Fascinating!”

Again, he doused the thing into the acid.

“Well, I must say, this is interesting. Tom, good for you.”

I had visions of my picture along with the object appearing in the centerfold of the London Illustrated News, the popular British magazine that occasionally featured archaeological finds.

Then Erik whirled around with the object and proclaimed, “Tom, it appears that you have found the first bicycle chain in history.”

It turned out that two coins I’d found in the morning dated to the reign of Victor Emmanuel II.

“If you find the rest of the bike,” Nancy laughed, “Leave it up there. I don’t need to waste my time cataloging it.”

Fred Licht eclipsed my discovery on the high Cittadella a few days later. At mid-morning we slobs down in the flats of the Agora could hear him shouting triumphantly, lifting something above his head. We could see his workers prancing about. Kyle Roberts and I raced up the steep slope to see what had been found. It was a breathtaking marble big toe, about six by four inches, masterfully carved with the nail and cuticle delineated perfectly. 5th century B. C.

Sjöqvist dispatched more workers up the hill and we dug the rest of the day, looking frantically for what we thought had to be the rest of a magnificent Herculean-sized marble statue. But we found nothing more. Sjöqvist at length concluded that the big toe was all there was. It was a votive toe. Someone had stubbed his real toe and had a marble replica made to be placed in a temple for a cure. Such votive body parts — hands, eyes, toes and even livers — in stone or terracotta were plentiful in the ancient world.

The first week was awful — cold rain and high winds. Despite the lousy weather, my crew seemed to be in high spirits — higher than mine, which I attributed that to the fact that they were getting paid every day. They were also getting used to the lanky “Dottore with the long, long nose,” which is what I was called in their impromptu songs. They didn’t know I understood Italian. Yet maybe they did and that was why they sang their jocular, Calypso-like songs. Soon they were making up songs about the “Dottore’s beautiful wife,” for Nancy hiked up to trench side to see what she described as “the brown mess.”

Although she felt fine we decided she should see a doctor, so we found a gynecologist in Catania. All seemed going well, but to be on the safe side, he recommended a series of shots available only in Italy. Erik was also receiving shots regularly. Licht, the former medical student, found himself going from Erik’s leathery ass to Nancy’s soft one, jabbing each patient every day. Whatever the shots were, they must have worked, as she never had any problems with that pregnancy.

When the women in Aidone heard about her condition, they gave Nancy some amulets to wear, for her good health and to insure the birth of a boy, for in Aidone, girls were anathema. Our spirits were lifted because she never experienced nausea or dizziness again during our time in Sicily and Europe. I figured on early November as the blessed date.

Sjöqvist and I made a foray north up a high plateau to the north of my first trench in which I had found nothing more exciting than a terracotta drain that linked with one in the lower Agora (cheers!). Suddenly Erik spotted on the surface a small bronze Ionic capital, only five inches across, perhaps an ornament from some luxurious table, dating late fifth or early fourth century B.C. It was so delicately designed that we decided that I should make a trial trench right on the spot. I was ebullient — no longer ugly drains or lumps of crude crockery to ponder over, no fragments of mass-produced common lamps, but, hopefully, stuff from “Park Avenue.”

Nancy quipped, “Perhaps this time you’ll do better than the bike, you know, unearth the first car in history.”

I was ready to go full speed ahead with my team. It had taken me weeks to get to know my workers and I had ranked them according to their talents.

Number one was Sufia, Filippo fu Giovanni, who had marvelously soft hands when he worked with the brush. He had a perpetual smile on his face.

Then there was Giovanni di Blia, a block of a man with untiring shoulders and subtle, fast fingers. He was so prescient that I almost imagined he could actually see things under the earth. Once I saw him start to cut into the earth with his small pick and stop it in mid-air to work with his fingers, freeing up a tiny terracotta head an inch below the surface.

Renzo, my third man, had brilliant eyes and could tell instantly whether a muddy shard was something to keep or cast aside.

The others were Buglisi the younger; Giuseppe Buglisi, the elder; Nino, the village retard, or so I mistakenly thought at first; and Orazio, the water boy who had a Mongoloid face, but was extremely bright.

I set about learning the local dialect. The vocabulary, Sjöqvist thought, was a mixture of ancient Phoenician, Latin, Arabic, Norman French and Italian. The word for water was not the Italian, “l’aqua,” but “l’egua,” closer to the French “l’eau.” To go to work was not “a lavoro” but “a travadyed,” from the French, “a travaille.”

I brought a notebook to the trench to record all the Aidonese words I could manage.

“Giovanni, start with the head and go down the body. Give me the words in Aidonese and I’ll try to write them down.”

So, in several hours of frantic and hilarious acting out, I had written the words for the male and female physiques. From “teshta,” head, through “ennata cou cou,” ass, and “pina,” penis, to the word for big toe.

After the anatomy lesson, I told them about how Nancy and I would be stared at and followed by bands of urchins in towns when we were looking at the monuments. How to get rid of them?

Don Ciccio said I should yell, “Va vatene carrouzit, c’sing z’diait.” I said it a dozens of times and finally got it to Don Ciccio’s delight. ‘Vah vahtenay carrouzeet, kasing zdeeyaayt,’ it sounded like.

“What the hell does it mean?” I asked.

“Via Va-va-tene, ‘Go away.’ Carrouzit. That means a shitty little pest. ’Ca sing,’ means ’I am.’ ’Za diait.’ ’I’m annoyed at you.”

Whatever it was, part Arabic and part Norman, it worked. From then on when a small throng of urchins badgered Nancy and me, I’d shout out the words and — zing — they’d take off.

“What do I say when I like something?” I asked Don Ciccio.

“You say, ’e boung!’ That is the same as ’e buono’.”

“When I don’t like something?”

“’Tinte, scarse, non e boung.’” Or, “tainted, lesser, not good.”

What was very “boung” was the enormous cistern we found. The mouth, a perfect circle, was a meter across. The main body was shaped like a giant milk bottle and after the neck widened out it measured nine feet across and was lined with lovely ancient creamy-white stucco. Giovanni and I dug out most of it, working with small shovels, passing up hundreds of buckets of earth to the top by ropes and pulleys. Halfway down in the cool, darkened interior Giovanni piped up, “Dottore, we’re going to find two skeletons of men at the bottom.”

I shivered as he told me of a local legend about two young men, friends for life, who had stumbled across the empty ancient cistern. One though he saw the glimmer of something at the bottom some twenty feet down. They got a rope and buckets and the more daring of the two went on down.

He found to his astonishment that the floor was covered with gold coins — hundreds of them. They lifted them all out and hid the treasure in a nearby abandoned sheep hutch owned by the family of one of the boys.

Ten buckets of gold coins were removed in the course of an afternoon. At dusk the boy in the cistern called out to his friend to send the rope down and bring him up.

Silence.

Days later when he figured his former partner had to be dead, his friend returned to the cistern and started to fill it in. He was horrified to hear his friend’s cracked voice begging for help, reminding him of all the things they had done together.

Full of remorse, he threw the rope down and told his friend that he would tie the rope around himself to brace himself so he could pull him out. But the one in the cistern, maddened by the perfidy of his former friend, grabbed the rope and yanked the other into the cistern. How long it took for them to die no one knew.

Giovanni pointed to what he claimed were marks of their scratching two thirds of the way down. And, at the bottom, we found the complete bones, rib cages and skulls — of a pair of goats.

“Giovanni, is there another part of the legend you didn’t tell me?”

“Si, Dottore, the part about the men turning into goats – this because they were both greedy and. . . .”

The head foreman, Signore Giuseppe Giucastro, would patrol the trenches randomly, eliciting muffled curses from the men. He looked like the living Michelin Fat Man — small plump face, piggy eyes, and little round, pursed mouth. He was one softly rolling mass of curves, from the Beret to his undulating stomach — ’’ou bidge” — to his fat thighs. The voice was plumpish, too, burbling the words in erratic phrases, always very loudly. He grunted and held out his hand limply and I grasped the pudgy fingers.

“What’s going on here?” he demanded sharply. Giucastro always sounded suspicious even when he was inquiring about the weather. He made a slow tour of the trench we’d just started, sorted through the meager shards we’d thrown into the boxes, grunted softly to himself, stroked his fat, little chin, turned to me and said, “You are going to find great things here, mark me!”

Don Ciccio smirked.

That afternoon, Giovanni called out to me, “I have something, ’’’ou canaow!’” He held out a large roof tile. Finally we seemed to have hit pay dirt. It was hard to work slowly and deliberately as we uncovered more and more thick and long terracotta roof tiles, most intact, larger than any we’d encountered before. The layer of tiles was three feet thick! Excitement rose to fever pitch. My God, what would we find beneath them?

Previous Chapter – Next Chapter