Opinion

5 Classic Hollywood Movies That Sculpted Our Image of Artists as Tragic, Irrepressible, Erotic Heroes

Filmmakers were enamored with artists long before Leonardo DiCaprio was set to star as Leonardo da Vinci.

Filmmakers were enamored with artists long before Leonardo DiCaprio was set to star as Leonardo da Vinci.

Ben Davis

We are living in the middle of an Artist Biopic Boom.

If you take a look at the Internet Movie Database’s timeline for films about artists and sculptors, the trend is clear: The closer you get to the present, the more films about artists there are, with biopics of Vincent van Gogh (At Eternity’s Gate) and Gerhard Richter (Never Look Away) in theaters, and films in the pipeline about Géricault, Leonardo, and even British painter L.S. Lowry.

It seems like the right time, then, to take a look at the history of this pocket genre. What are its classics? What are its quirks? How does it limit or open new avenues to tell stories about art to the broader public?

I’ve been going through the catalogue. Below are highlights of the films from 1930s through the ‘50s. They were made well before today’s enormous fascination, but represent the period when patterns were set.

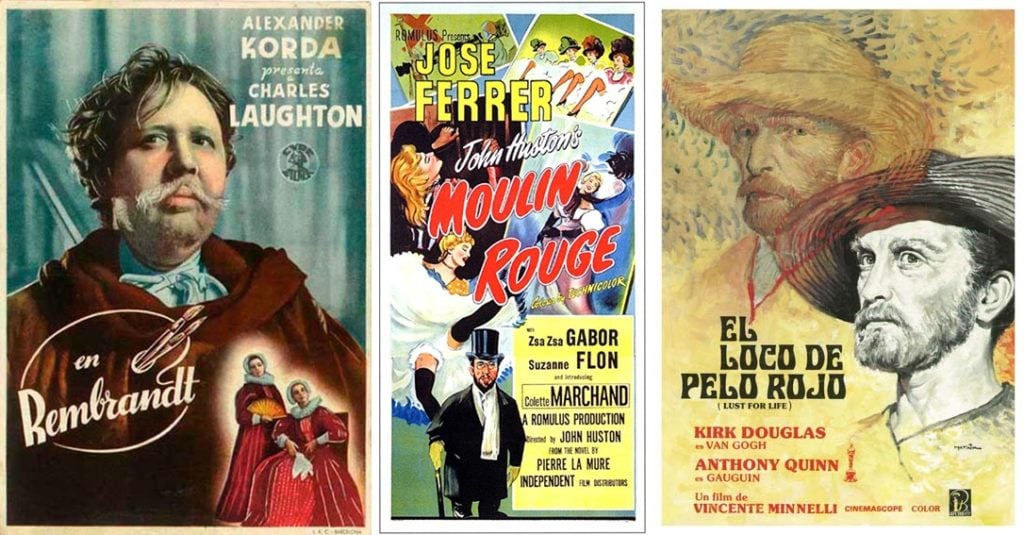

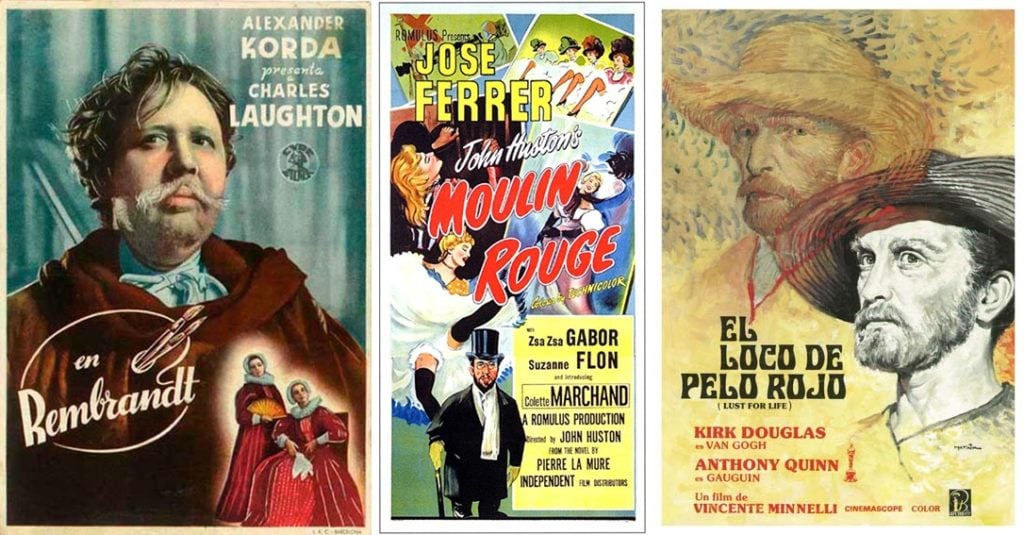

Two posters for The Affairs of Cellini (1934).

The first film of note in IMDB’s artist biopic category, The Affairs of Cellini, is also an outlier in the genre as a whole: It’s a comedy.

But then, Benvenuto Cellini (1500–1571) is an artist with an unconventional place in the canon: He’s known as much for his rakish memoirs as for his sculpture, and his most famous piece is an improbably sensual gold salt celler depicting the Roman gods Neptune and Terra. He isn’t exactly known for romantic or tortured imagery.

In look and feel, The Affairs of Cellini is basically a swashbuckling Renaissance bedroom farce. There are fleeting moments in which the artist is at the bellows in his workshop, and references to his skill as a goldsmith, but the focus is mainly on the man as a lovable, lusty cad (considerably softening Cellini’s actual biography).

We are only moments into the film when Cellini (Fredric March) tries to seduce his model, Angela (Fay Wray, post-King Kong), in a scene that includes both charming dialogue (Angela: “You haven’t even looked at my bobbin work.” Cellini: “There is a time for bobbin work and a time for love!”) and a horrifyingly chipper scene where he negotiates with the model’s depraved mother for the right to her virginity.

What follows are sword fights, intrigue (“Whoever destroys Cellini before the plates are finished destroys himself,” he warns a foe), and bed-swapping between the artist, his model, and the randy Duke and Duchess of Florence (played by Frank Morgan, best known as the Wizard in the Wizard of Oz, and Constance Bennett).

What It Contributes: The fascination of this earliest artist film is, notably, with the artist’s lifestyle, not the artist’s craft—which serves as a neat symbol of the fact that idea of the artist as an exotically amoral and passionate creature is the real bedrock of the genre.

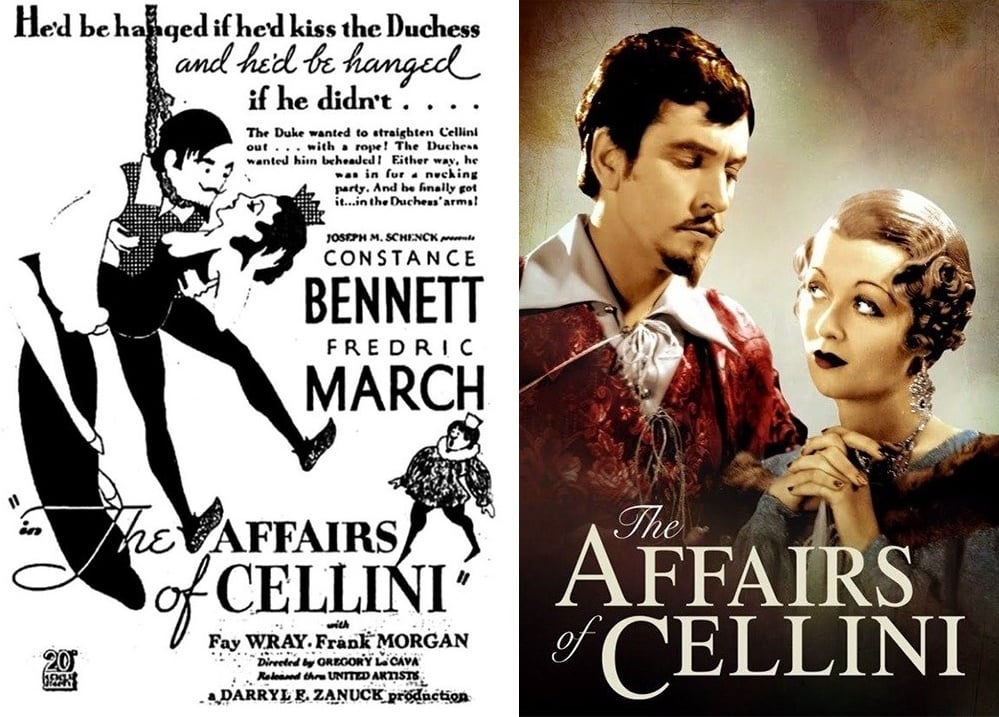

Cover for Rembrandt (1936).

Alexander Korda’s Rembrandt remains surprisingly watchable even today, moving nimbly from the Old Master’s proud salad days to world-weary old age, hitting all the big beats of the Rembrandt mythology at a steady clip.

There is, for instance, the Artist-as-Deep-Soul scene, wherein Rembrandt (Charles Laughton, giving a very good balance of haughty and soulful) spellbinds a tavern full of crass colleagues into silence with an epic speech about his muse, Saskia.

There’s the Artist-as-Misunderstood-Genius scene, where we see Rembrandt unveil the Night Watch as a philistine public gawps and laughs at the famous masterpiece and demands their money back. (It is an old saw that the public rejected this most famous artist’s most famous painting.)

And there’s a wonderful Artist-as-Suffering-Martyr ending, when the aged Rembrandt, having lost everything, is accidentally swept up, unrecognized, into the entourage of the hot new painter in town. In a moment that mirrors his first big speech about Saskia, the cocky new art star and his groupies propose toasts, before goading the mysterious old man they have adopted into giving his own.

“Vanity, vanity, all is vanity,” he intones haltingly, quoting Ecclesiastes—at which point they recognize him as fallen legend Rembrandt van Rijn, and stare, aghast.

What It Contributes: Just two years after The Affairs of Cellini’s stagy eccentricity, Rembrandt basically offers up the classic artist-movie formula. There’s still brawling and romance, but the pageantry is all grounded in the pretense that the film is trying to educate us about a real historical figure’s story. More importantly, the focus has moved to the artist’s suffering psychology and the conflict between genius and a philistine society.

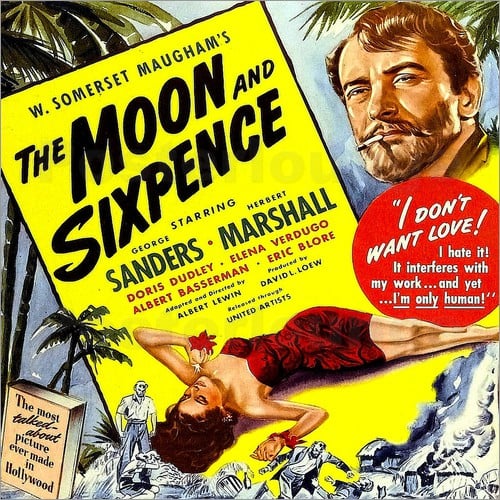

Promotional image for The Moon and Sixpence (1942).

This stands as one of the smartest spins on the genre—partly because Albert Lewin’s film is not chained to the facts of a real-life artist’s life, but is based instead on the tart 1916 novel by W. Somerset Maugham.

Still, the real-life target is clear. The story centers on a painter (George Sanders, who later won Best Supporting Actor as the theater critic in All About Eve) whose arc from boring stock broker to Parisian painter to Tahitian adventurer is clearly meant as a riff on Paul Gauguin. Just a very, very British version of Gauguin.

“This is the story of Charles Strickland, the painter, whose career has created so much discussion,” reads the opening card. “It is not our purpose to defend him.” Nor does it really explain him. The film has a kind of mystery set-up, with a writer (Herbert Marshall) trying to figure out what led Strickland to leave his wife and drop out of society—and finding him weirdly, inhumanly happy with his isolated new life.

An emotionally brutal second act sees the starving artist sheltered in the home of a kindly Dutch painter, Dirk Stroeve (Steven Geray), who is convinced of the historical importance of Strickland’s art. Strickland repays the favor by coldly humiliating him. Stroeve’s wife, drawn into the spell, impulsively leaves him for Strickland, later to commit suicide when he fails to reciprocate her love.

Yet even after his life has been ruined, Stroeve finds himself spellbound by a nude portrait of his wife made by Strickland, begging the diabolical painter to let him support his art. In effect, the film uses Stroeve to show the worship of artistic genius as a kind of pathology that locks you into a toxic relationship, excusing all abuse.

Oddly (or not, considering the time the film was made), the story’s genteel but nasty skepticism falls off in the third act, when the movie turns to Tahiti, which is really the part of the Gauguin legend ripest for de-mythification. There, Strickland finds some unearned redemption in the love of a Tahitian child bride (Elena Verdugo) before painting his greatest works on the walls of the hut where he is shut in for leprosy—the final symbol of how creative passion drives artists beyond the bounds of society and infects all who come into contact with it.

What It Contributes: The weirdness—and the fun—of The Moon and Sixpence is how it inverts expectations of the artist myth: Strickland is not a passionate and life-affirming figure; he is enigmatically ice-cold. And he is not a symbol of humanity crushed by society. The greater an artist he becomes, in fact, the more he destroys those around him. The Moon and Sixpence rebuts the artist-as-heroic-adventurer-of-the-soul myth before Gauguin himself even got the official biopic treatment.

Poster for Moulin Rouge (1952).

John Huston’s follow-up to The African Queen was this biopic of Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec (1864–1901), shot in keyed-up colors to evoke the Post-Impressionist’s posters.

José Ferrer gives Toulouse-Lautrec a stiff but convincingly surly braininess while Huston uses various tricks to render the artist’s famously short stature. The basic thesis of the film is that Toulouse-Lautrec, haunted by feelings of inadequacy due to his deformed legs, is goaded on to artistic greatness (and to drink) by repeated failures in love.

This includes a scene in which a debauched prostitute-muse, Marie Charlet (Colette Marchand, nominated for Best Supporting Actress for the role) humiliates him, causing the artist to attempt death by gas in his studio apartment—only to be abruptly struck by inspiration to finish the design for his poster Moulin Rouge: La Goulue (1891), art calling him back to life.

The best dramatic beat, however, comes later when Toulouse-Lautrec discovers the real La Goulue (Katherine Kath), once a Moulin Rouge star celebrated by the artist but now drunkenly ranting on a street corner about her former glory, with the intriguing but undeveloped theme that his art has played a role in her downfall.

“They say men kill the thing they love the most,” Toulouse-Lautrec intones solemnly. “My posters played their part in destroying the Moulin. With great success, it became respectable. There was no place for La Goulue—or any of us.”

Moulin Rouge also features what is likely the most on-the-nose version of the Artist Deathbed scene put to film: Sick and defeated by life, the artist lays in a stupor as his father (also, strangely, played by Ferrer), who once threatened to have him “horse-whipped” because his art defiled the Toulouse-Lautrec name, now begging forgiveness: “Do you hear me Henri? Your paintings are to hang in the Louvre! I didn’t understand! I didn’t understand!”

Thereupon, the expiring Toulouse-Lautrec sees a cavalcade of ghosts of the characters from the Moulin Rouge (including Zsa Zsa Gabor) that he immortalized in his art, who arrive to usher him into the hereafter with a rousing can-can.

What It Contributes: It’s a John Huston film, so the big theme is the drama of masculinity. The male artist’s “diabolical muse,” who both inspires and torments, is made to bear the symbolic burden of representing the exciting world that lays beyond bourgeois alienation as well as the perils of going there. The trope lives on in many subsequent films.

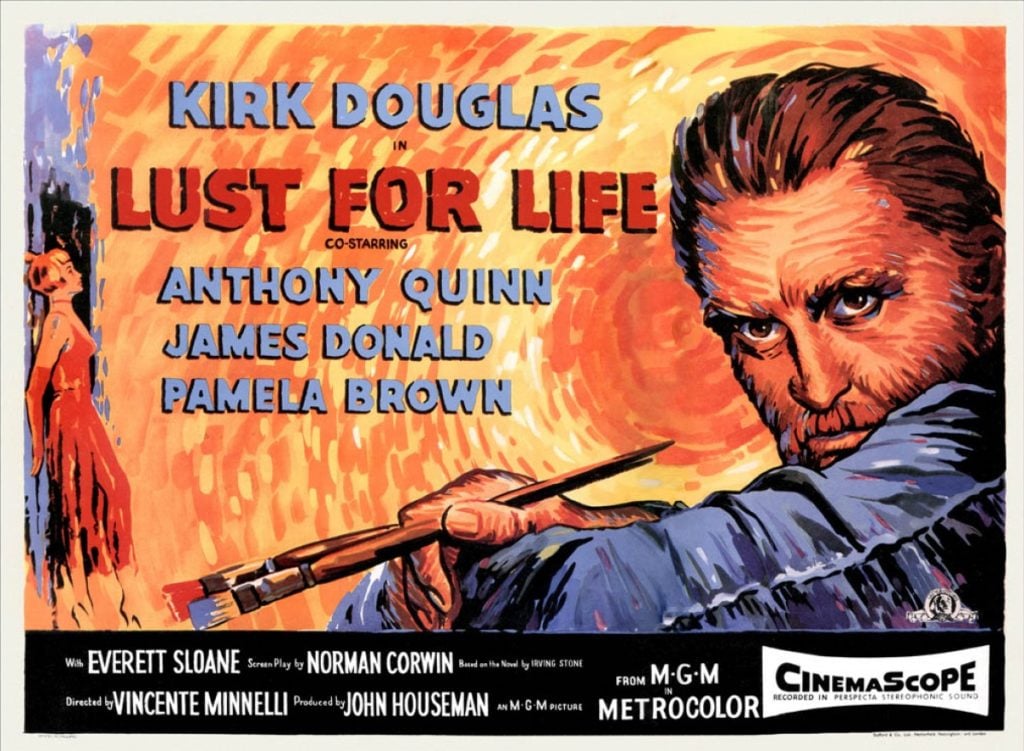

Poster for Lust for Life (1956).

Vincente Minnelli’s opus is still probably the artist biopic, even 60-plus years on. It’s hammy and paints with a broad brush, but it’s also colorful and devotional in a heart-on-its-sleeve way that you can’t get away with anymore, which cuts against the dreariness of all that creative anguish.

Lust for Life hits all the familiar beats of the van Gogh story; indeed, it’s probably a big reason that those beats are so familiar. Kirk Douglas’s vaguely New York-sounding Vincent van Gogh has a brawny intensity, as the maladjusted Dutchman slowly finds and then loses himself in his art.

The trailer focuses on van Gogh and drinking buddy Paul Gauguin (Anthony Quinn) arguing about women, proving that sex drive is the easiest metaphor to explain artistic drive to the public. (There was a time when Quinn’s Gauguin holding court about how he “likes ‘em fat and mean and not too smart” was considered zesty bravado, I guess.)

But the film itself does make some charming effort to illustrate the artists’ creative as well as personal disagreements, including an earth-shaking shouting match over the merits of Barbizon School painter Jean-François Millet.

What It Contributes: Lust for Life ratified the artist-martyr tale as Oscar bait. Douglas was nominated. Quinn won Best Supporting Actor, and credited Gauguin’s ghost, which he says taught him how to hold a brush.

But—as everyone clearly knew, based on how the trailer was cut—what makes the film work is not the solitary suffering part. It’s the van Gogh/Gauguin bromance (which doesn’t even get going until halfway through). One thing about artist-martyr stories is that you know how they end. All that righteous pain can be terribly cloying. Having an equal and opposite sparring partner gives it some dynamism.

As it happens, Lust for Life also crystallized the two artist archetypes that repeat and mix in different patterns again and again going forward: the artist whose spirit is too pure and innocent for the world (van Gogh); and the artist whose raw passion inspires an awakening in others (Gauguin). We’ll see these types again.