Art World

Art to Dye For: How the Knitting Community Is Weaving the Art of David Hockney and Helen Frankenthaler Into Their Craft

These yarn companies are bringing the palettes of art-historical heavyweights to knitting enthusiasts around the world.

These yarn companies are bringing the palettes of art-historical heavyweights to knitting enthusiasts around the world.

Kyle Schnitzer

Roxanne Yeun doesn’t know precisely when she first thought to interweave art and yarn. More than a decade ago, she visited the Dalí Museum in Florida with her husband, Neville, and became curious about Salvador Dalí’s creative process. Standing in the museum, Yeun resolved to discover a way to apply Dali’s creativity to yarn.

After she returned home, Yeun, the owner of Canadian-based yarn company Zen Yarn Garden, went to work. She tried to apply the vibrant ambiguity of the 1970 painting The Hallucinogenic Toreador to yarn. Her creation featured bold blacks toned with the lighter colors used in Dalí’s work.

“I was like a mad scientist in the dye room,” Yeun told artnet News. “I needed to have some control for coloration. I needed an inspiration for me to decide how to put colors together on yarn so it could be harmonious and inspirational.”

Yeun is one of a number of yarn-makers who are taking inspiration from art history’s greatest masters to develop technically complex yarns that pay tribute to art history. And after taking a look at the elaborate process behind their creations, you’ll never look at technicolor knitted scarves the same way again.

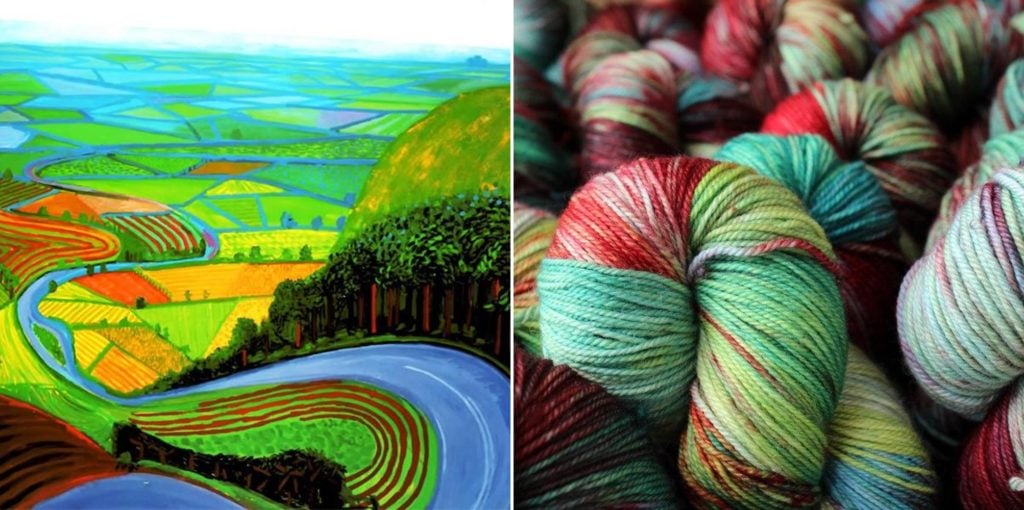

Left: Hockney’s Garrowby Hill. Right: “Art Walk” Series Yarn based on the painting.

Yeun expanded her Dalí experiment into a full series called “Art Walk” in 2007. With the help of her husband, a chemical engineer, she has created dozens of hand-dyed yarns inspired by art from all corners of the world. Her influences include major works by Pablo Picasso and Jackson Pollock, as well as broader art-historical movements like Expressionism and Surrealism. The resulting patterns are full of life, like the duo’s airy rendition of David Hockney’s painting Garrowby Hill (2000) and Roxanne’s dark, splattered recreation of Pollock’s Convergence (1952).

Zen Yarn Garden’s Pollock inspired “Art Yarn.”

“There’s that element in a pod that can be very random,” said Neville Yeun. “Because we’re dyeing with a purpose, we don’t just put dyes in a pod. We want something to represent the painting.”

Colors and textures are determined by the dyeing method. Hand-painted yarns give dyers more control when it comes to color distribution, which creates areas with purposeful coloration. But kettle dyeing, done in large pots, gives the yarn more variety and can even appear more abstract.

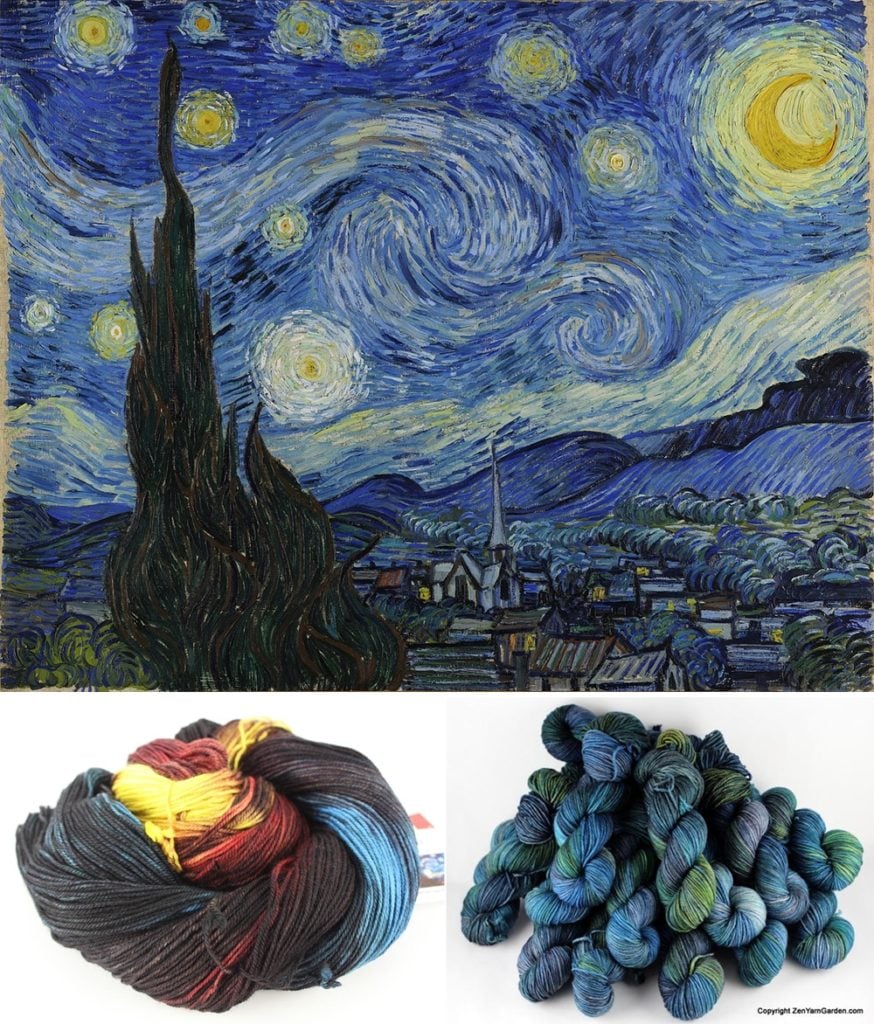

And just as two people experience the same painting differently, Roxanne and Neville have created different yarn interpretations of the same work. Zen Yarn Garden created two versions of Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889), for example, their most difficult project. The first version, created by Roxanne, focused on the muted tones of the town beneath the sky and featured mostly blues and blacks. Neville’s version focused on Van Gogh’s moon, highlighted with yellows and lighter tones he saw in the painting.

Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889), and both versions of the “Art Walk” yarn. Courtesy of Zen Yarn Garden.

“There are different feelings we can pull from that painting,” Roxanne said. “It’s someone seeing it different than me. I think the artist, too, wants you to have a personal experience with their work.”

Yarnmakers go to great lengths to ensure that their material evokes the same feeling as the artwork that inspired it. Amanda Hu, owner of the New York City-based yarn producer Hu Made, wanted to pay homage to some of her favorite artists in her “Art Yarn” collection, including Claude Monet and Edward Hopper, but also pull from contemporary artists like Faith Ringgold and Yayoi Kusama.

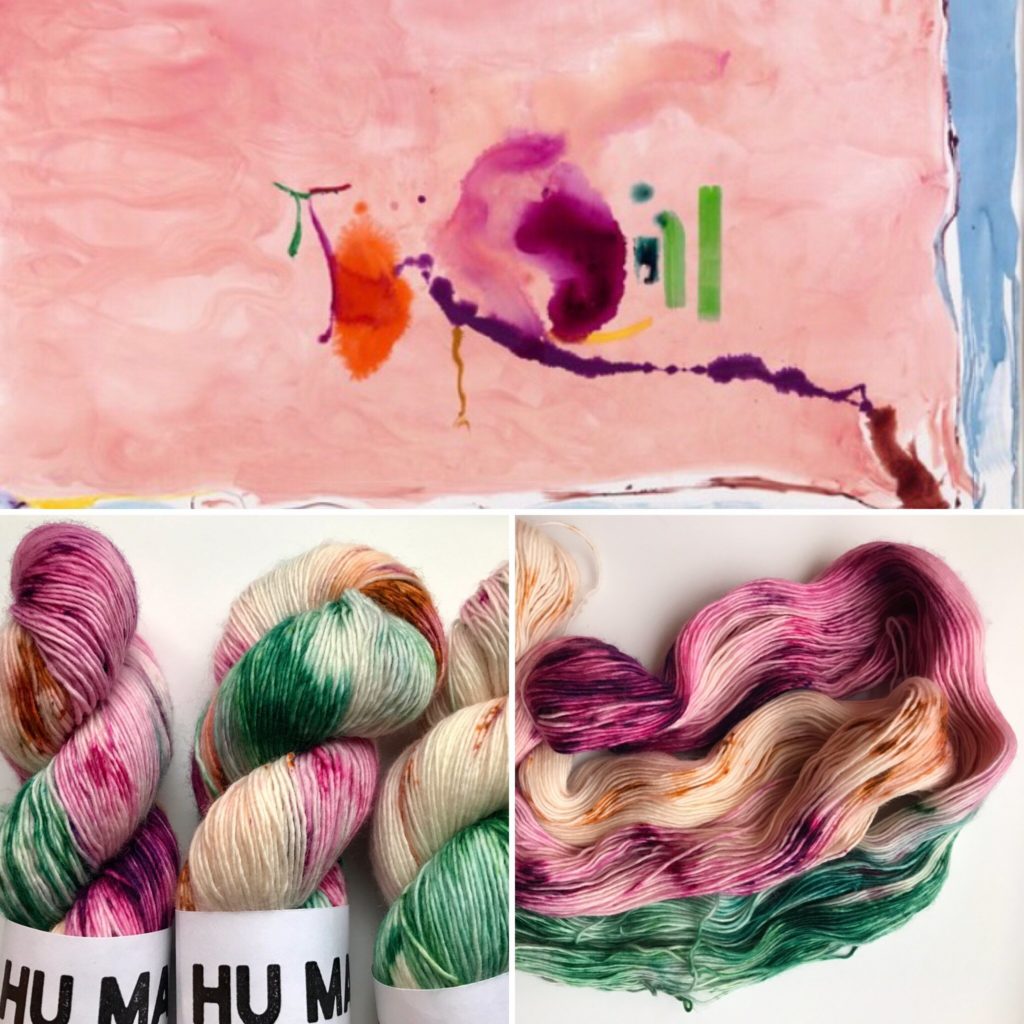

Hu Made’s “Art Yarn” series, Flirt based on Helen Frankenthaler’s 1995 work.

“Emotion and sensitivity are essential to both my fine art and yarn practice,” Hu, a mixed-media artist who also specializes in printmaking, said. “I love the idea of wearable art. For my yarn, while I’m literally painting color onto each yarn skein, I also have to consider what the yarn will look like knit up. That yarn creates a new canvas or art surface made by each individual knitter.”

In Hu’s recreation of Helen Frankenthaler’s 1995 painting Flirt, she struggled to capture the painting’s massive scale and the fluidity of the paint. “I have always been interested in Frankenthaler’s color field paintings and her prints because of their nuanced and unexpected color interactions,” Hu said. “Since her work is very gestural, this lends itself to how I like to apply dye to yarn, in this case creating broad swaths of washed color.”

Malabrigo’s “Matisse Blue” and “Botticelli Red.” Courtesy of Malabrigo.

Bringing the spirit of a painting into yarn comes with other technical difficulties, too. The weight and material of the yarn can pose obstacles that alter the appearance of each skein. Wool and other animal fibers require different care and ingredients compared to dyeing plant-based sources like cotton or linen, which require modifiers such as vinegar or bark.

Uruguayan heavyweight Malabrigo produces hundreds of colors of yarn inspired by art history (“Matisse Blue,” “Botticelli Red”). Founder Antonio Gonzalez-Arnao says it can take 20 laboratory tests before Malabrigo finds the right color. Small modifications like shadows or spots can change how one skein appears in the lab from dye lot, which makes each skein unique.

“I use the world of the art in general to decide the tones and combinations,” he said. “I always have on my mind [Josef] Albers’s lessons about color and combination regarding the position and quantity.”

Malabrigo’s “Persia” Sock yarn (L) and Nobu yarn (R) inspired by the Frieze of Archers courtesy of the Louvre.

One of Malabrigo’s most abstract colors, “Persia,” takes inspiration from the ancient Persian brick war mural Frieze of Archers. Gonzalez-Arnao found a way to transfer the mural’s glazed brightness to the opaque yarn by focusing on the soldiers’ grays and the backdrop’s blues, playing with tint to infuse the piece’s texture and colors into the thread. But when applying it to different weights, like Mecha (bulky yarn) or Sock (single-ply), the results are entirely different.

“I used to retouch the colors in different weights if they need it,” Gonzalez-Arnao said. “But in this case, I didn’t do it because they represent different shades of the wall. It can be random.”

And just as an artist loses control of an artwork as soon as it leaves the studio, so a yarnmaker loses control of his or her creation as soon as it is purchased, pulled apart, and reassembled into a new form by the knitter.

“We’re dealing with colors and we’re both dealing with mediums,” Roxanne Yeun said. “[Dyeing] creates some emotion with the colorations and some connection to the artists.”