Politics

Before the Smoke Cleared From the Capitol Riots, Curators Were Out Looking for Artifacts. What Should They Do With Them Now?

The Smithsonian hopes its collection of the highly loaded objects will help preserve the history of that dark day.

The Smithsonian hopes its collection of the highly loaded objects will help preserve the history of that dark day.

Sarah Cascone

A year ago this week, the very fabric of U.S. democracy was threatened, as insurrectionists looking to overthrow the results of the presidential election stormed the Capitol building where Congress had gathered to certify Joe Biden as the winner of the electoral vote.

Before the smoke from the tear gas had cleared, curators and historians were already beginning to grapple with the complicated question of how best to preserve the historical record of the day for future generations—and what role the day’s physical artifacts would play in that process, reports the Washington Post.

“We tend to think of historical research as focusing on documents and letters, things like that. But these are objects that are connected to real people who were on the ground,” Claire Jerry, the political history curator at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History in Washington, D.C., told Artnet News. “Objects become a more tangible form of evidence.”

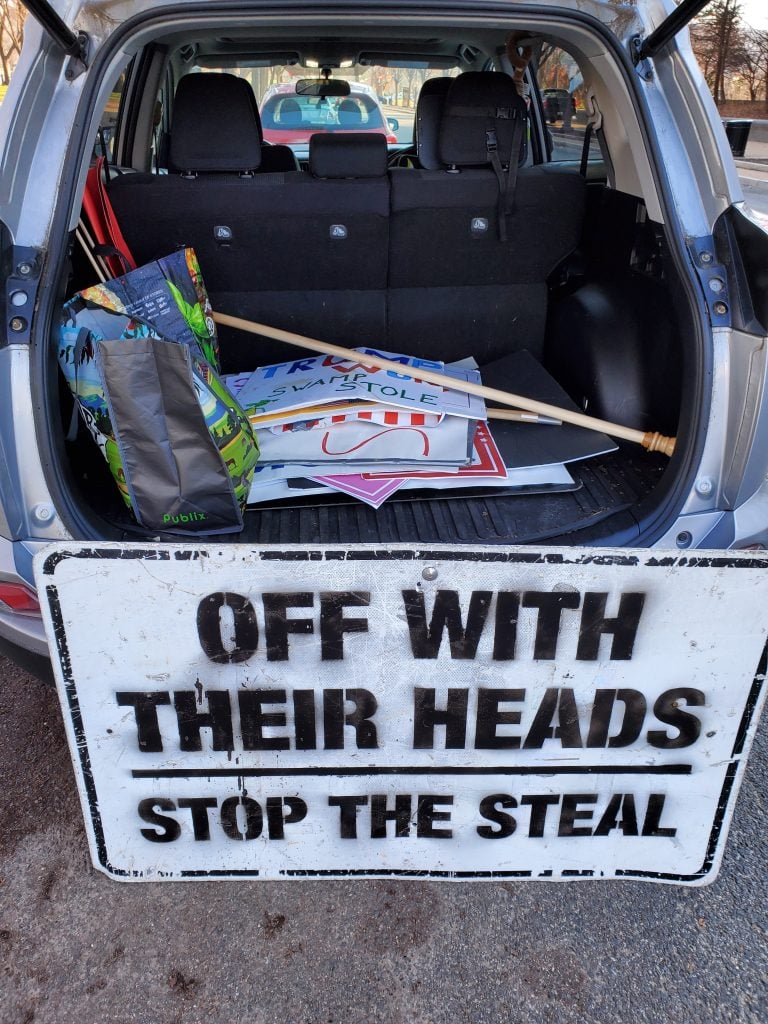

The morning after the attack, Frank Blazich, the National Museum of American History’s curator of modern military history, made his way to the National Mall, sifting through trash cans for objects of interest.

Photo by Frank Blazich, courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

The posters, signs, and other ephemera he found were the beginning of a collection that currently numbers 80 items.

This kind of rapid-response collecting has become increasingly common for museums.

“Sometimes you actually know you’re in a time that history is being made—that you’re a part of it, but it’s also happening unto you,” museum director Anthea Hartig told Artnet News. “It’s our near-sacred duty to collect as broadly and thoughtfully as we can to document these intersecting crises.”

Freelance photographer Madeleine Kelly donated this protective vest, in which she was stabbed while documenting the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol, to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

To that end, the museum has also invited people to donate their January 6 objects, like the protective vest freelance photographer Madeleine Kelly wore while attempting to document the event. It is torn where a woman participating in the riot stabbed Kelly with a knife.

Another donation came from New Jersey Representative Andy Kim: the blue J. Crew suit he was wearing when he was forced to evacuate the Capitol, and when he returned hours later to help pick up debris before Congress resumed session.

And then there are the military patches donated by D.C. local Pat Savoy, who spent three months handing out snacks to the National Guard and other military personnel dispatched to guard the Capitol.

The soldiers, whose units came from all over the country, gave their insignias to Savoy’s toddler son Noah.

Noah Savoy meeting members of the National Guard protecting the Capitol. Photo courtesy of the Savoy family.

Participants in the rally and the attack that followed, on the other hand, have not reached out about donations.

“I would not expect to have those conversations now,” Jerry said. “With major events like this, it’s maybe years later that someone comes forward. Sometimes it’s a family member—maybe they’re not proud of what they did, but they recognize the historical significance. I think we will be collecting for January 6 for decades to come.”

Other artifacts will come to the museum as criminal investigations conclude and law enforcement is able to release objects currently being held as evidence.

“Displaying criminality always has to be done very carefully, and always has to have the benefit of time,” Hartig said. “We have a history of working with our partners in federal law enforcement, and there will be a moment where those objects will be converted into a space where they can be considered artifacts.”

Supporters of US President Donald Trump gather on the West side of the US Capitol in Washington, DC, on January 6, 2021. Photo by Andrew Caballero-Reynold/AFP via Getty Images.

Possible examples include the orange noose that hung from a gallows erected on the lawn in front of the Capitol said to be in FBI custody. A Dutch journalist picked it up with the thought that it belonged at a museum.

While the Smithsonian hasn’t made any arrangements for that particular artifact, objects that speak to racist rhetoric pose especially thorny problems.

“Nooses and the Confederate battle flag, flown inside the U.S. Capitol—those are highly loaded symbols of violence against Black Americans and voter suppression, on a day that was supposed to celebrate a relatively straightforward, peaceful transition of power,” Hartig said.

That same impulse is what inspired the U.S. Capitol Historical Society to launch a “January 6 Oral History Project,” which began conducting interviews late last year.

“The discussion about January 6 and the memory of January 6 had become so partisan, we were afraid we were going to lose the factual memories about what happened on that day,” society president Jane Campbell told Artnet News. “We felt the best way to preserve those memories was to give people the opportunity to share their story.”

The plan is that the society’s oral history will become publicly available in partnership with a university.

Supporters of US President Donald Trump enter the US Capitol’s Rotunda on January 6, 2021, in Washington, DC. (Photo by Saul Loeb/AFP via Getty Images.)

“All the things that are left behind, their stories become more compelling when the people who were there tell the stories themselves,” Campbell said.

“My hope for the entire historic record is that between the Smithsonian and the U.S. Capitol Historical Society, with the Senate and the House, the Library of Congress and the National Archives, we will have a very deep and rich collection that helps tell the story of that day,” Hartig said.

Part of that history includes objects that belong to the government, from the physical voting records that certified the election to the onsite sculptures, murals, and paintings in the Capitol that had to undergo careful conservation following the attack, particularly to combat the effects of the tear gas used to disperse the mobs. Curators from the Architect of the Capitol estimated $25,000 in repair costs, but the figure could have easily been much higher.

“The miraculous thing was that there wasn’t wanton destruction,” Campbell said. “There was a big mess that had to be cleaned up very carefully so as to not damage the art and the architecture, but it was more disrespectful than destructive.”

The Smithsonian history museum has no immediate plans to display objects from January 6, but some of the artifacts will likely begin to get cycled into the institution’s existing political displays in years to come.

“The events of January 6 were a part of the election of 2020, they were connected to the [first] impeachment hearings, to the inauguration that was coming up, they were part of the the pandemic story,” Jerry said. “And we’re still talking about how the events of last year might influence upcoming elections. This is a one year anniversary, but we’re a long way from the end of this story.”

“Museums collect so we don’t forget,” Hartig added. “We create spaces for conversation where we can explore what it means to uphold the fragility of our democracy—which was on full display that day.”