The storming of the US capitol by a pro-Trump mob on January 6 brought insurrectionists in close contact with Congress’s historic art collection, which includes monumental John Trumbull paintings and 100 statues of notable Americans.

But while the artworks appear to have escaped direct harm from the violent invaders—who smashed windows, destroyed AP camera equipment, vandalized Nancy Pelosi’s office, and killed one capitol police officer—many of the items they left behind may could end up in a museum.

The Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History is looking to collect “objects and stories that help future generations remember and contextualize January 6 and its aftermath,” wrote director Anthea M. Hartig in a statement.

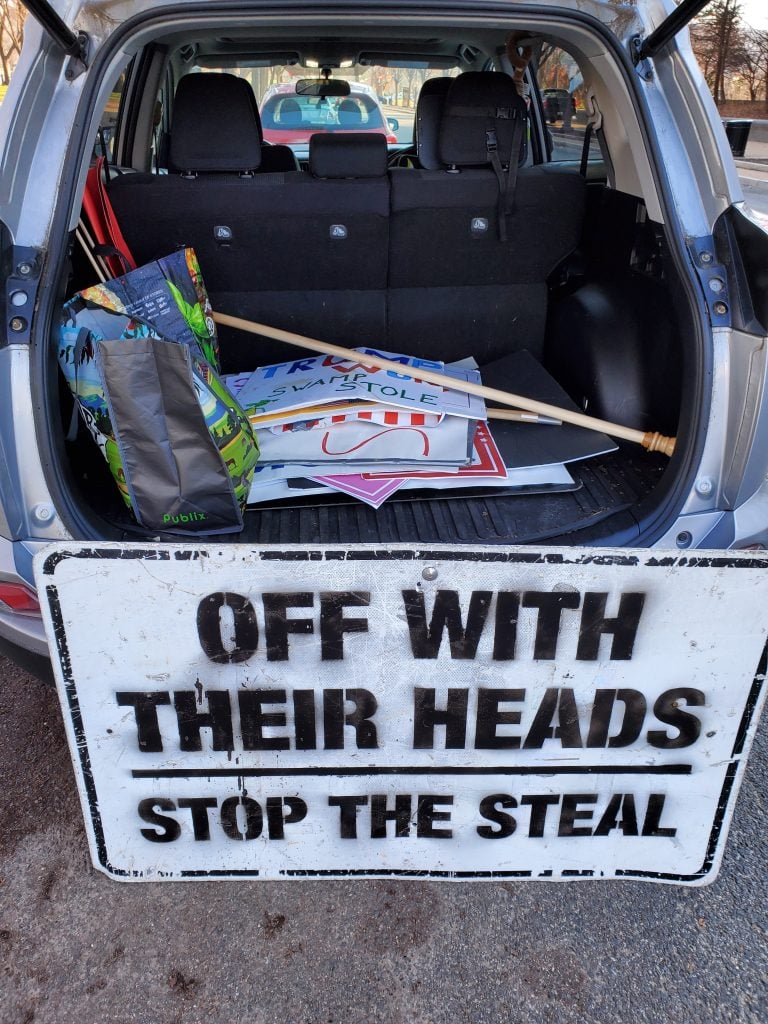

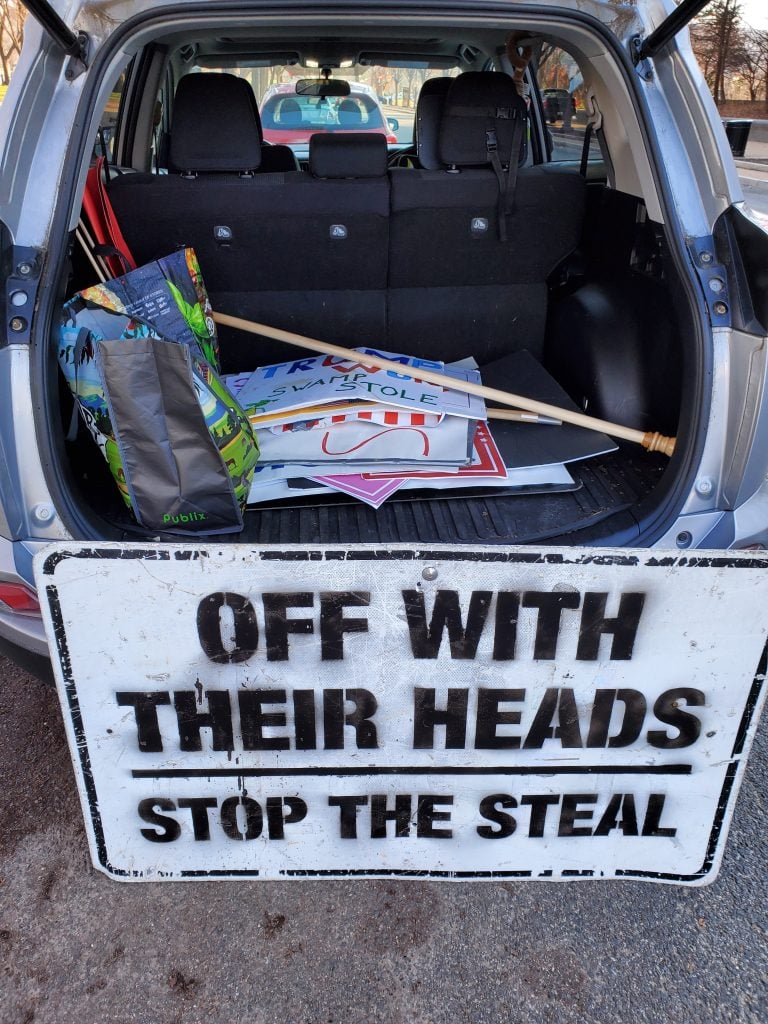

The museum has already collected ephemera from the historic day—which marked the first breach of the capitol since the War of 1812—including pro-insurrection stickers and flags and a sign that reads: “Off with their heads: Stop the steal” (The House and Senate collections will preserve Pelosi’s broken office placard.)

“As a historian I want everything preserved,” Jane Campbell, president of the US Capitol Historical Society, told the Washington Post. “I think the people who did the attack on the capitol are insurrectionist, immoral, and bad news all the way around… but if they left stuff behind, it should be preserved and studied later. We have to look at, ‘What did we learn?’ ”

A number of signs, banners and other ephemeral items from the pro-Trump rallies and demonstrations on the National Mall that led to the storming of the US Capitol on January 6, which are headed to the collections of the National Museum of American History. Photo by Frank Blazich, courtesy of the National Museum of American History.

One prominent artifact that historians may want to try to pursue is the bearskin and buffalo horn headdress worn and American flag spear wielded by Jake Angeli, the self-proclaimed “QAnon Shaman” who was arrested over the weekend for disorderly conduct and unlawful and violent entry of a restricted building.

Angeli, whose real name is Jacob Anthony Chansley, was highly visible in media coverage of the event. The shocking image of him—bare-chested, heavily tattooed, face painted—presiding over Mitch McConnell’s hastily vacated desk on the dais of the Senate chamber underscored the serious nature of the unprecedented event.

A pro-Trump mob confronts US Capitol police outside the Senate chamber of the U.S. Capitol Building on January 06, 2021 in Washington, DC. Photo by Win McNamee/Getty Images.

As Congress reconvened late that night to finish certifying the election of Joe Biden and Kamala Harris, it was amid shattered panes of glass, upturned furniture, and assorted detritus left behind by the marauding invaders.

Even after the halls were cleared of debris, the question of conservation remained for the building’s historic artworks, including a 19th-century statue of President Zachary Taylor, which appeared to have been smeared with blood. (Works on loan to the capitol from the Smithsonian and the National Gallery of Art are confirmed to have escaped damage.)

“Statues, murals, historic benches, and original shutters all suffered varying degrees of damage—primarily from pepper spray accretions and residue from tear gas and fire extinguishers—that will require cleaning and conservation,” an Architect of the Capitol spokesperson told the Post. (The building is home to three separate art collection, belonging to the House of Representatives, the Senate, and the Architect of the Capitol.)

John Trumbull, Declaration of Independence (1819) hangs in the US Capitol rotunda. Courtesy of Architect of the Capitol.

Seven of historic artworks, including portraits of James Madison and John Quincy Adams and a marble statue of Thomas Jefferson, “were covered with a corrosive gas agent residue,” a spokesperson for the clerk of the House told Artnet News. “The conservators and the materials scientists Smithsonian are going to test the works and determine what the extent of what the damage is and how to remove it.”

“The main concerns would be the solvent that’s used as the carrier agent for the spray,” a New York-based conservator told Artnet News. “Whatever the chemicals are, whether it’s delivered as gas or an aerosolized liquid, if those land on artworks, they can undergo a chemical reaction with whatever compounds the artworks are made from.”

Removing the residue, “is going to be super time consuming and costly,” she added. “Most conservators probably don’t have experience with tear gas or pepper spray.”