Opinion

The Art World Has Agonized Over Its Reliance on Airplanes. But That’s the Wrong Way to Think About Reducing Carbon Emissions

There are far better ways to focus our anti-carbon efforts.

There are far better ways to focus our anti-carbon efforts.

Nicholas Russell

I recently attended a session on climate change during a London “unconference”—a meeting that’s led by its participants—on the theme of the “Future of the Art Market” in the UK.

One provocation gained traction early: that the art market has a responsibility to minimize its carbon emissions by reducing airline freight miles traveled as a result of hosting and attending exhibitions.

Someone floated the proposition that we replace the shipping of physical works of art with virtual exhibitions. Using augmented reality to broaden the accessibility of artworks is a wonderful idea, and already one gaining traction among a number of early adopters. Virtual shows offer not only high-quality replications, but also entirely new immersive experiences. Plus, content can be delivered to smaller cities and museums that may not be able to financially support larger exhibitions.

But the group was more excited by the notion that replacing physical art shipments with virtualized experiences could reduce carbon emissions, rather than creating new and more accessible experiences. Given the climate emergency, their view was to pursue any and all discretionary savings of carbon possible.

Superficially, that may appear to be a successful thought exercise. But I disagree. The percentage of carbon emissions caused by art-industry air travel is infinitesimally small—and our activist efforts would be far better spent elsewhere.

To successfully change industries, we must first understand the costs to all participants in a market or ecosystem. Global populations moving from traditional cars to electric cars, for example, may cost Germany $20 billion a year and impact 1 percent of the country’s labor force. While it’s easy to reduce one’s personal emissions by buying an electric car, millions of people buying electric cars change employment markets. And these disruptions echo into entire societies.

In a well-intentioned quest to reduce carbon emissions, the unconference group not only incorrectly estimated the carbon savings from reducing art miles, but also failed entirely to account for any greater implications. They shifted responsibility for managing carbon emissions from governments and consumers, into the art market value chain itself. They would increase burdens on artists, galleries, and other players in the value chain to the point of potentially removing those players altogether. And the result of reducing physical art shipments around the world is unlikely to cause a significant decrease in emissions.

How much does air freight shipping contribute to climate change? Photo: Creative Commons.

When I asked the group what percent of overall emissions the aviation sector as a whole represents, the general response was 20 percent, which is fairly typical. Then when asked what share of that was air freight, the response was about half. Meaning, air freight generates 10 percent of total global carbon emissions in a given year. The actual numbers on air traffic contributions to annual carbon emissions is an order of magnitude less than those assumptions.

Airline traffic as a whole generates 2 percent of global carbon emissions. The reason people tend to assume air travel contributes greater emissions has to do with the visibility of airplanes in our lives (what’s known in psychology as availability bias). Consumers, it seems, are much more aware of aircraft—a minor contributor—than of the much greater impacts of energy and heat produced for cities, buildings, and ground transport, which are the greatest contributors.

Air freight accounts for between 7 to 10 percent of total air traffic. Therefore, air freight may produce a total of about .2 percent of global carbon emissions—50 times less than the heuristic estimate.

The International Air Transport Association estimates that it ships five to six million tons of air freight. If all 40 million pieces of art sold a year were 13.3-inch-square canvases and packaging weighing an average of 26 pounds were shipped via air freight, that would be 520 tons, or .9 percent of total air freight. Air freight is 10 percent of total air traffic and air traffic is 2 percent of global emissions. Therefore, one could estimate moving the entire annual art market by air freight would create .00184 percent of total global carbon emissions. And, given that only a subset of global transactions will actually ship by air, the total actual annual carbon contribution from shipping art continues to collapse to an infinitesimal number.

So why do so many art professionals amplify carbon contributed by art air freight from an infinitesimal amount into one of the preeminent issues facing the global art market?

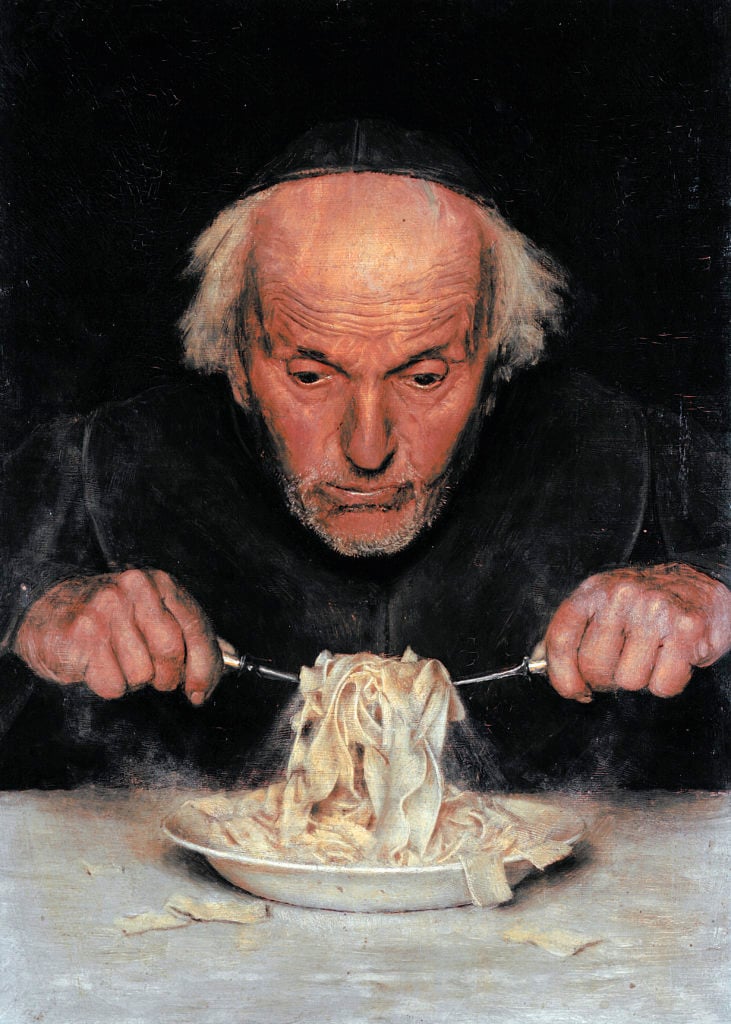

The pasta eater, by unknown artist, 19th century. Museo Nazionale delle Paste Alimentari, Rome Italy. Photo by Leemage/UIG via Getty Images.

We need to look instead at what is known in sustainability as “lifecycle costing,” which accounts for all the carbon created in the production, distribution, and consumption of a product. In 2010, a UK grocery store attempted to reduce the total carbon emissions of a major staple product line—dry pasta. The company assessed emissions at different stages of the product’s life, including production, distribution, and consumption. Distribution produced a minor fraction of the total carbon footprint. The majority of carbon was produced growing wheat, and at the moment of consumption: boiling water to cook the pasta.

The impact of carbon generated by dry pasta has been reconfirmed over the last decade, most recently in a 2019 study in Italy. Distribution of locally produced pasta generated less than a half pound of CO2—7 percent of the product’s total carbon emissions. Distribution of globally-produced pasta generated .67 pounds of CO2—10 percent of the product’s total carbon emissions. And distributing pasta from global markets generated 40 percent more carbon than local markets on an absolute basis. However, locally produced created 6.5 pounds of carbon total, whereas pasta from global markets created 6.3 pounds of carbon—2 percent less carbon.

While pasta from global markets generated 34 percent more carbon in the distribution phase on its life, in the process overall, pasta from foreign markets generated less carbon. Even though they traveled further, those products were more efficient in other lifecycle stages. Finally, regardless of sourcing locally or globally, production and consumption together represented over 80 percent of total carbon generated. In terms of carbon, distribution costs—or savings—were comparatively irrelevant.

Why had both consumers and the grocery store singled out distribution as the obvious point of carbon savings, when it turned out to be one of the most minor contributors? The same reason that, a decade later, a group of art professionals in London arrived at the same answer for the art market: Both groups amplified the negative contribution of the lifecycle costs they valued least—and reduced the contributions from the costs they valued most. With art, as with pasta, the greatest carbon emissions come from the last stage—consuming it.

The Whitney Museum of American Art’s new building became the city’s first LEED-certified art museum. Photo: Ed Lederman.

When it comes to the art market, the reality is that venues and audiences produce the vast majority of emissions. Reducing the total carbon emissions of art consumption requires reducing emissions of built environments—our buildings, climate control systems, energy generation sites—and transportation. These are the domains of consumers and governments.

As beauty is created by the beholder, so, as it turns out, are the majority of carbon emissions. We must reduce carbon emissions, but we must not unfairly dismiss our responsibilities as citizens and consumers, using collective cognitive biases as justifications to encumber simple activities like the art market’s use of air freight. Given the intertwinement of fossil fuels in human society, we cannot simply judge carbon emissions as good or bad. We must continuously interrogate the benefit of carbon emissions versus costs, and we must ensure the numbers are right.

As the coronavirus now closes borders to human travel, we must be aware, in some cases, that pandemic-related border closures may serve agendas and intentions that were otherwise frustrated. Borders may not reopen as quickly as they were closed. If we as individuals are to be increasingly be restricted in our movement, we must ensure freedom of movement for our ideas, whether as digital manifestations or as physical objects. This may well mean shipping more art, not less.

Like pasta, the majority of carbon emissions of art lie beyond distribution. Unlike pasta, where the majority of environmental impacts are split between agriculture and cooking, the majority of environmental impacts from art lie in its consumption, whether jet-setting to art fairs, or cooling, heating, and lighting national galleries with fossil-based fuels. Where the art world can direct its well-intentioned climactic energies does not have to do with the art itself at all, but rather with designing buildings.

In 2016, the engineering firm Arup showed that the built environment generates 40 percent of human carbon emissions. This includes audiences attending exhibitions and related contributions from hosting both artworks and audiences in climate-controlled facilities.

Efficiency is a first totem of sustainability. Consume less energy. Then shift remaining consumption from fossils to renewables. We can maintain or even increase art air miles and reduce lifecycle carbon footprints—meaning we can share and sell more—if we also reduce the energy footprints of galleries, studios, warehouses, and the other spaces we use. These building energy footprints are both much higher impact and also invisible compared to air traffic. Seeing that clearly, as it turns out, makes all the difference.

Nicholas Russell is a Californian living in London. He is currently Entrepreneur In Residence on the Conception X deeptech startup program where he works with PhDs from top UK universities and corporates to commercialize scientific research. Previously, he ran real estate technology startups, and spent five years as a management consultant working on electric vehicle development in China, and lifecycle costing, renewable energy, and smart cities in Europe. Russell also has a background in the creative industries and works with emerging art-tech companies.