Art History

How Dalí Became One of the First Artist Pioneers in the Field of Holographics

The surrealist saw holograms as a way to move beyond the human subconscious into a new cosmic paradigm.

The surrealist saw holograms as a way to move beyond the human subconscious into a new cosmic paradigm.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

When holographics were first invented in the late 1940s by the “father of holography” Dennis Gabor, the ability to make 3D records on a 2D surface quickly took off among scientists who found applications in medicine, the military, and engineering. It took slightly longer for the more creative possibilities of holographics to be realized. Who better for the task the legendary modernist Salvador Dalí, who never once shied from the strange or surreal?

Dalí was the first person who came to mind when holography expert Selwyn Lissack decided it was high time holographics be recognized as an artistic medium. He reached out to the artist in 1971. “I’ve been waiting for you to call,” was Dalí’s characteristically enigmatic response. If true, it can only have been a premonition, since he had never previously heard of Lissack.

Salvador Dalí poses next to his holographic art. Photo courtesy of Paul Perry.

For the eccentric Spanish artist, who had already spent decades plumbing the depths of the human subconscious, there was an obvious appeal to making art that could break free from the confines of linear space into what he dubbed “the Dalí dimension.” In his Anti-Matter Manifesto from 1958, he had already proclaimed his desire to shift his focus onto “the exterior world and that of physics [which] has transcended the one of psychology.”

By Lissack’s account, Dalí saw their collaboration as a chance to make a bold voyage of discovery into the “cosmic paradigm.” The pair began working out of his suite at the St. Regis Hotel in New York City.

Over a period of five years, they would produce seven holographic artworks. One of the very first, Polyhedron and Basketball, was inspired by a photograph of basketball players making a jump shot that Dalí had spotted in the New York Times in 1972. He apparently told Lissack that, in his mind, the players looked like they were becoming angels, and in his version they appear to reach beyond the printed page to grasp hold of planet Earth.

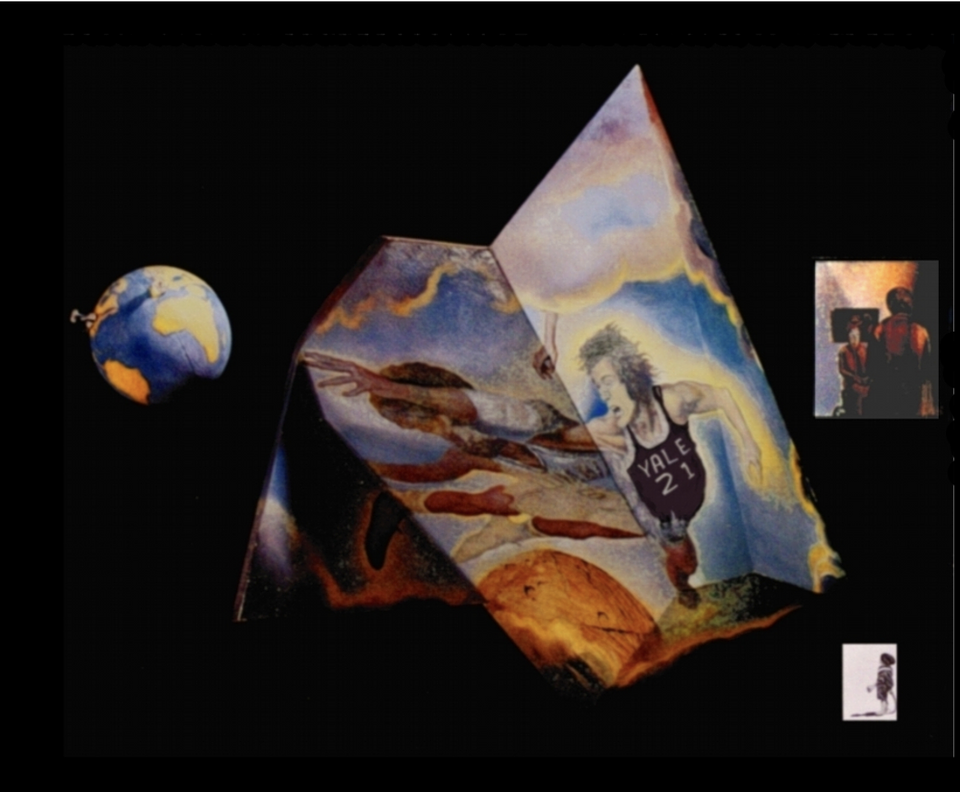

Salvado Dalí, Alice Cooper’s Brain (1973). Image courtesy of Cuban Fine Arts.

Another highly experimental work was Alice Cooper’s Brain, an homage to the outlandish American rock star. After the two became friends, Cooper sat for Dalí in 1973, draped in multi-million dollar diamonds from the jeweller Harry Winston and rotating on a turntable. A model of his brain crafted by Dalí and covered in the artist’s trademark ants and topped with a chocolate éclair was suspended on a red velvet cushion behind Cooper’s head. The musician was also instructed to clutch a model of Venus de Milo like a microphone.

“I wasn’t exactly sure what was going on,” Cooper later told Anther Magazine. “Dalí was a character who was so mythical, you didn’t really want to say anything. For me, it was like meeting Elvis or The Beatles.”

Salvado Dalí, The Melting Clock. Image courtesy of Cuban Fine Arts.

References to past fixations of Dalí’s also surfaced in other works, like The Melting Clock. Conceived in 1975, it was one of his last uses of this classic motif made famous by his painting The Persistence of Memory (1931). The work could never be completed in Dalí’s life time because the lighting system used for playback was too hot, so the blueprint was entrusted with Lissack who was eventually able to realize Dalí’s vision in the 21st century by using a fiber laser.

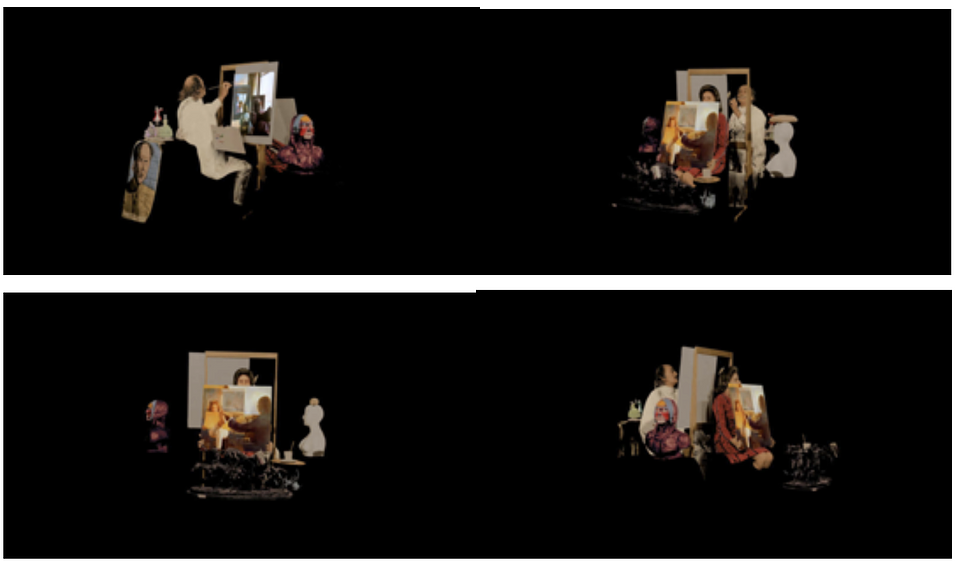

In 1976, Dalí turned the lens back on himself to make a self-portrait that again blends images taken at different angles to offer a rotating 360-degree view of the artist painting his wife Gala. The work references a painting produced a few years before, Dalí Seen from the Back Painting Gala from the Back Eternalized by Six Virtual Corneas Provisionally Reflected by Six Real Mirrors (1972-3).

Salvado Dalí, Dali Painting Gala (1976). Image courtesy of Cuban Fine Arts.

Creating and displaying holographics was challenging in the 1970s, a time before LEDs. The pair would have had to use bulky and expensive equipment that was prone to overheating, like lasers, mercury-arc lamps, and halogen lights. Dalí was lucky to work under the technical supervision of Lissack, an early pioneer of the use of holography to make commercial products. He founded the International Holographic Corporation in 1969, and among his earliest products was the King Vitamin ring, a toy that came with packets of Quaker Oats and reminded children to take daily vitamins.

Dalí’s groundbreaking holographics are available from Cuban Fine Arts gallery in Brooklyn, New York.

More Trending Stories:

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments

Gerhard Richter’s Abstract Alpine Landscapes Will Converge at a Three-Venue Survey in St. Moritz