Art History

Edward Hopper’s ‘Nighthawks’ Captures the Isolation of American Modernity. Here Are 3 Things You Might Not Know About It

A Hemingway short story may have inspired Hopper's iconic scene.

A Hemingway short story may have inspired Hopper's iconic scene.

Bobby McGee

“Ed refused to take any interest in our very likely prospect of being bombed—and we live right under glass sky-lights and a roof that leaks whenever it rains,” wrote Edward Hopper’s wife, Josephine, in the days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Hopper was busy, perhaps avoidantly so, at work on a new canvas, soon to be named Nighthawks.

Hopper’s scenes of city and country life—houses and gas stations, trains and movie theaters, bedrooms, and offices—present the realities of everyday America infused with a voyeuristic, psychological complexity. During a period where abstraction grew increasingly dominant, Hopper explored the creative potential of the Realist tradition.

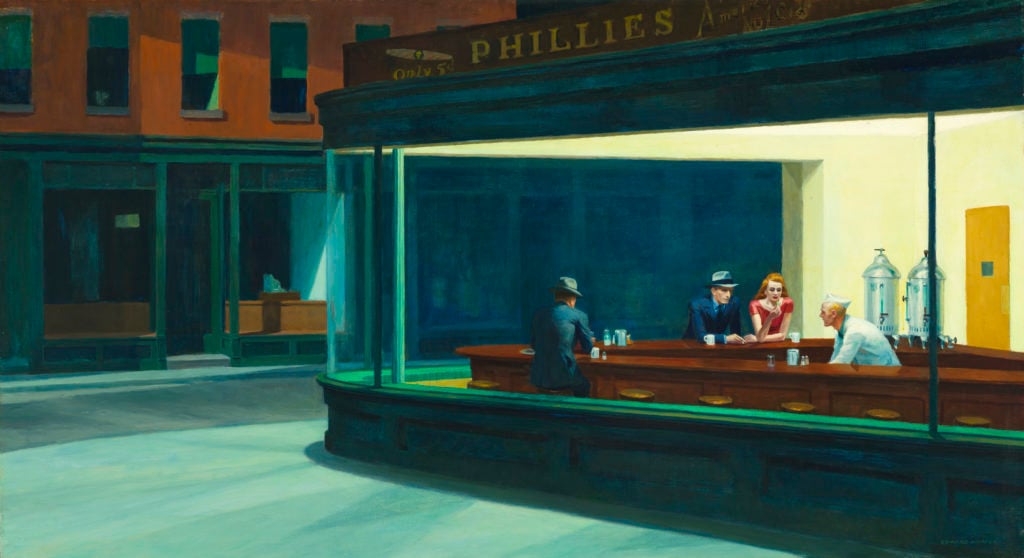

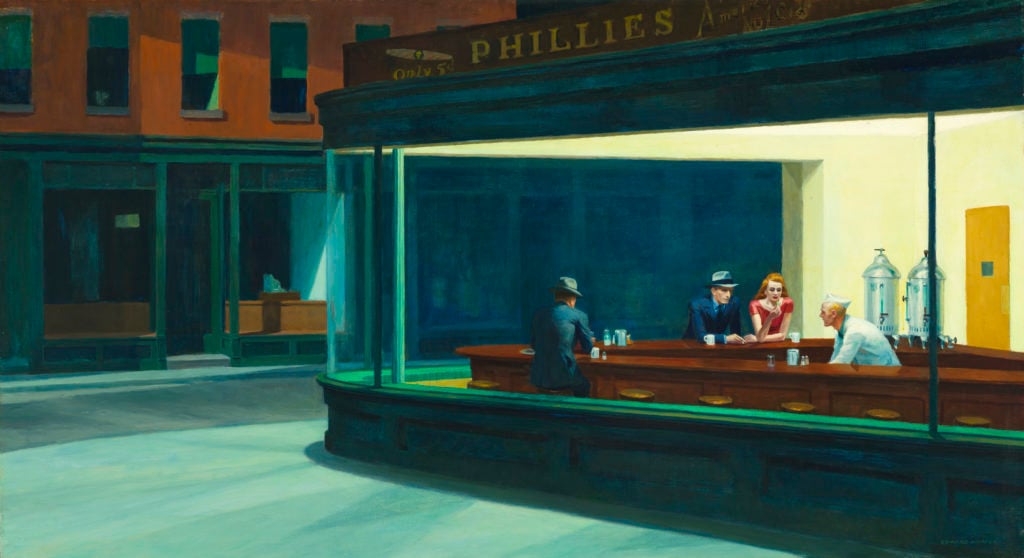

Certainly Hopper’s most iconic painting, arguably his masterpiece, Nighthawks is one of the most well-known works of the 20th century—a classic scene out of the “American Imagination,” to borrow from the title of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s 1995 Hopper retrospective. The piece was acquired shortly after its completion by the Art Institute of Chicago, where it remains today.

Late at night, four solitary figures occupy a restaurant diner on a deserted street corner. Fluorescent light seeps out through the large plate-glass windows and stains the sidewalk an eerie, shadowy green. No door exists to welcome the viewer, who is made all too aware of their role as spectator, left out on the street.

Inside, although the man and woman face us, they avert their gaze. The woman holds a sandwich; the man, a cigarette. Their fingers, resting on the sleek cherry-wood countertop, appear almost to touch, but don’t. Seated alone, the other patron indulges his drink and coffee, seen only from behind; the white-uniformed counter attendant gazes out the window absentmindedly. Everyone in this disquieting scene is absorbed in their own inner worlds—a microcosm of the urban proximity to anonymity.

Hopper’s paintings are often interpreted as echoing the overwhelming isolation of modern life, especially working in the era of the Great Depression and WWII. In some ways this is due to his arrangement of space, which is vast but never empty, full of agency that acts upon or consumes its surroundings. Asked about this sense of alienation in Nighthawks, Hopper replied, “I didn’t see it as particularly lonely. I simplified the scene a great deal and made the restaurant bigger. Unconsciously, probably, I was painting the loneliness of a large city.”

Hopper was an avid movie-goer and theater patron, and his works have a distinctly cinematic staging, like set pieces. Because of this, one sometimes gets the feeling that something just happened, or is about to. Yet his paintings resist narrative. Within his highly orchestrated ambiguity (Hopper made 19 studies for Nighthawks) lurks a kind of foreboding, psychic tension.

Perhaps picking up on this, the late art critic Peter Schjeldahl devised a test for determining a Hopper: “run your eyes passively along the walls. When you’re jarred, like a car hitting a rock in the road, stop. Nearly always, you will be gazing at a Hopper.

With the holidays upon us, and nostalgia running high, we’re taking a closer look at a work whose familiarity both excites and unsettles.

Giorgio de Chirico, Piazza d’Italia (1916). Image courtesy Axel Vervoordt.

Hopper’s early studies with Robert Henri, a Realist of the progressive Ashcan School, and his frequent trips to Paris to see the Impressionists influenced his style. Less well-known is Hopper’s affinity with Surrealism. In December 1936, he and Jo both visited the Fantastic Art, Dada and Surrealism exhibition, organized by Alfred Barr at the Museum of Modern Art. Impressed by their use of color, he quipped that the Surrealists were better artists than they realized.

Hopper was a lifelong reader, so it’s not surprising the writings of Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung piqued his interest. Their insights into dreams and the unconscious, which deeply influenced Surrealist imagery, permeated popular discourse around him. Hopper even conceded, “So much of every art is an expression of the subconscious, that it seems to me most of all of the important qualities are put there unconsciously, and little of importance by the conscious intellect.”

Although Nighthawks and other works don’t reach the overtly fantastic renderings that defined Surrealists like Salvador Dalí and René Magritte, Hopper’s realism here becomes fantasy. The sculptor George Segal captured this when he noted, “What I like about Hopper is how far poetically he went, away from the real world.” Nothing supernatural materializes, yet Nighthawks exudes a sense of mystery and suspense, recalling the kind of foreboding, vaguely sinister street scenes by Giorgio de Chirico—also admired by the Surrealists. The sense of solitude the viewer feels as a detached witness, trapped outside the diner, suggests the kind of suspended time often experienced in dreams. The figures, too, in their geometric rigidity and inscrutable expressions take on the perplexing, wooden one-dimensionality of dream “extras.”

Nighthawks also evokes one of Surrealism’s favorite concepts, the uncanny. According to Freud, this strange, not-quite-right feeling manifests in the transformation of something once-familiar into the threateningly foreign. Here the sprawling windows, while protective during the day, expose the figures’ vulnerability by night. In contrast, the dark, second-story windows of the adjacent building conceal the possibility of a threat lurking inside.

Art historian Margaret Iversen noted of Hopper’s work, “The uncanny return of the past is a sort of denatured nostalgia.” We can see this readily in Nighthawks, where a fondness for the classic American diner is degraded—formally, through thrusting diagonals, intense colors, contrasting light, and empty space—into an airless purgatory.

Wikimedia Commons.

Hopper had a profound love for poetry and literature, dating back to his childhood. Like the Surrealists, he was drawn to the French Symbolist poets. During the early days of their relationship, he and Jo exchanged verses by Paul Verlaine, later turning to Stéphane Mallarmé and Arthur Rimbaud (both of whom appear in André Breton’s first Surrealist manifesto). Throughout their marriage, to pass time, or while doing chores, they took to reading out loud to each other—pieces from The New Yorker, history books, or works by Shakespeare, T. S. Eliot, Robert Frost, and André Gide, to name only a few.

Charting this, the art historian and Hopper authority Gail Levin has linked both the setting and suspenseful mood of Nighthawks to Ernest Hemingway’s 1927 short story “The Killers.” Set in a diner at night, the story follows two hitmen as they seek out their target. Hopper admired the piece enough to send a letter of support to the editor of Scribner’s shortly after it ran, calling it “an honest piece of work.”

As much as Hopper turned to literary sources for inspiration, other writers and poets have similarly drawn on Nighthawks in their practice. Joyce Carol Oates develops a backstory for the man and woman in her 1989 poem “Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, 1942”: “she’s contemplating / a cigarette in her right hand, thinking that / her companion has finally left his wife but / can she trust him?” Similarly, Anne Carson imagines, “I wanted to run away with you tonight / but you are a difficult woman / …On a street black as windows / with nothing to confess / our distances found us.”

This kind of curious imagining is what John Updike has termed Hopper’s “temptation.” He dangles a story that doesn’t ever materialize and entices viewers to fill in the narrative, to find the before and after, and to wonder. The best Hopper’s do this. Certainly Nighthawks, but also a work we might see as its inverse, Sunlight in a Cafeteria (1958), a daytime scene set within a restaurant. Ultimately, Updike concludes, these efforts are mere “projections that slide off the painting, leaving it just where it hangs.”

Detail of Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks.

Hopper and Jo posed for all the figures in Nighthawks except for the counter attendant (Hopper used a mirror to paint himself), but that doesn’t mean he was completely invented. In 1928, Hopper created a painting titled Captain Ed Staples depicting a man wearing dark suit pants and a vest over a white shirt. Recalling a typical New England sea captain, the figure was a composite-type Hopper dreamed up based on Coast Guard officers and other sailors he encountered during his time in Cape Cod, where he and Jo spent their summers.

The following year the painting was destroyed in a train crash while returning from an exhibition at the Cleveland Museum. Yet Staples managed to live on, appearing in other works under different guises. In Gas, 1940, Jo identifies the lone pump attendant as “the son of Capt. Ed Staples.” About Nighthawks, she writes that the restaurant worker was “practically ‘Capt. Ed Staples.’”

Jo wrote that she considered this fictional captain to be an alter ego for Hopper himself. His repeated inclusion and their frequent referencing suggest a deeper significance and connection. For all the talk of the anonymity of the Hopperesque world, Staples might exemplify the early lessons from his teacher Henri, of art as an expression of the artist and of life. Echoing this Hopper stated: “I select certain subjects because I believe them to be the best mediums for a synthesis of my inner experience.”