Art History

A Fanciful History of Fairies in Art, From Renaissance Depictions to Romantic Shakespearean Visions

We trace these magical, miniature beings through centuries of art and culture.

We trace these magical, miniature beings through centuries of art and culture.

Katie White

Puck, Tinker Bell, the Fairy Godmother herself: fairies have fluttered throughout literature, theater, and bedtime stories for centuries. These magical beings, often diminutively scaled, have a sizable presence in many folklore traditions, including Celtic, Slavic, Nordic, Germanic, and French. “Fairy” is a word with a complex etymology, taking its root in the Latin word fata, or fates—which is appropriate, as these mischievous and mercurial beings are said to tamper with the lives and destinies of the humans they encounter.

Fickle and fanciful, fairies have also inspired artists, a symbol of the effervescent beauty of spring and the flora with which they are closely aligned, but also, as spiteful sprites who speak the irrationality of existence. As we approach the autumn solstice on September 23, we’ve searched out art-historical appearances of these supernatural entities and assembled an incomplete but vibrant and fantastical history of fairies in Western art.

William Blake, Oberon, Titania and Puck with Fairies Dancing (ca. 1786). Collection of the Tate.

Though fairies had existed in so-called pagan cultures for thousands of years, after the rise of Christendom, belief in fairies was denied, with these beings often classified as demons. Though still maintained in folklore, visual representations began to change during the Renaissance. In Britain, where fairy painting would reach a zenith, William Shakespeare’s comedic play “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”—which was written around 1595—particularly popularized fairies, with its story of humans and fairies mingling. The play’s characters famously included Fairy King Oberon and Queen Titania, along with Puck, and a legion of other fairies, whose individual origins are rooted in Northern European folklore.

The popular play had a long-lasting influence on artists, and while the Victorian era would experience a true fury for these winged beings, by the mid to late 18th century, Romantic artists had begun to turn to fairies as a motif for dreams or otherworldly experiences; notably, the Swiss artist Henry Fuseli and the British artist William Blake. Blake’s watercolor Oberon, Titania, and Puck with Fairies Dancing (ca. 1786) depicts the concluding moment of Shakespeare’s play when the feuding Oberon and Titania warmly reconcile. Puck claps a celebratory beat and the fairies Moth, Cobweb, Peaseblossom, and Mustardseed dance in a circle, dressed in gauzy, almost Grecian gowns, with flower petals in their hair.

Henry Fuseli, Titania and Bottom (ca. 1790). Collection of the Tate.

Fuseli, who spent the majority of his career in Britain, often focused on supernatural subject matter. Like Blake, he also painted fairies from “A Midsummer Night’s Dream” but chose a darker theme. Titania and Bottom (1790) depicts a moment in Act IV of the play when King Oberon casts a punishing spell on Queen Titania, leading her to fall in love with Bottom, a weaver whose head has been transformed into that of a donkey. Here, Titania’s attendant fairies gather around clad in contemporaneous 18th-century attire. Fuseli added other peculiar attributes, including a woman with a gnome-like figure on a string on the right, embodying the feminine’s victory over the masculine, along with doll-like children—the creations of witches—on the right. Fuseli also took an interest in fairies from other Shakespeare plays, painting Queen Mab, another fairy queen, who is mentioned in Romeo and Juliet as “the fairies’ midwife.”

Richard Dadd, Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke (1855–1864). Collection of the Tate.

Fairy paintings as a genre originate largely in the work of the troubled British artist Richard Dadd (1817–86). Born in Kent, Dadd was a preternaturally talented artist even as a child, heading to London to attend the Royal Academy of Art at age 17. Dadd had early successes, but when his mental health suffered, he was sent back to Kent to recover. Believed to have experienced delusions, Dadd would later be admitted to Bethlehem psychiatric facility, and later Broadmoor Hospital. In these institutions, and under the care of progressive doctors, Dadd was encouraged to paint, and his works often imagined intricate fairy worlds. His most famous painting, The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke, he returned to again and again over the course of a decade between 1855 and 1864.

Dadd had an incredible talent for detail, creating highly elaborate miniature scenes in such works as Titania Sleeping (1841) and Contradiction: Oberon and Titania (1858). These images were widely influential to British artists in the decades that followed. Aside from fairy paintings, he created a number of seascapes, portraits, and more. Many of his paintings are on view at Broadmoor to this day—and though he is quoted predominantly by visual artists, Freddie Mercury’s 1974 song “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke” recollects the musician’s first encounter with Dadd’s eponymous painting.

John Anster Fitzgerald, Fairies in a Bird’s Nest (ca. 1860). Collection of the Legion of Honor, San Francisco.

A flight of fairy fever swept through the U.K., inspired in part by Dadd’s paintings, lasting from the late 19th into the early 20th century. The Victorians were fascinated by ideas of the paranormal, and while depictions of fairies were rooted in mythology, theater, and folklore, this seemingly delightful preoccupation was in fact a reaction to the social travails of the era.

Artists including Joseph Noel Paton, Edwin Landseer, John Anster Fitzgerald, and Sophie Gengembre Anderson offered images celebrating the hidden magic of idyllic, untouched landscapes, and tapped cultural unease at the dawn of industrialization. Meanwhile, as an era of Victorian puritanism shifted British social norms, the hedonistic world of fairies offered a reprieve for artists and viewers alike. Impish and amoral, fairies of the Victorian era are often seen indulging in pleasures at other’s expense. In Fitzgerald’s painting, Fairies in a Bird’s Nest (ca. 1860), fairies languish romantically in a nest but have seemingly shoved out a bird’s egg to do so. Below them, the egg is devoured by goblins. Other times, Victorian-era fairy paintings hint at man-made indulgences; Fitzgerald’s painting titles, including The Pipe Dream and The Captive Dreamer, have led many to think the artist frequented the era’s opium dens, where laudanum was popularly consumed.

The first of the Cottingley Fairy photographs from 1917, taken by Elsie Wright and showing Frances Griffiths ringed by “fairies.”

Could fairies be real? Sir Arthur Conan Doyle was among the many convinced of their existence by a series of five photographs taken between 1917 and 1920 by two young cousins, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths, who lived in Cottingley, England.

The photographs pictured the young cousins, who were 9 and 16 years old in the earliest images, surrounded by the diminutive beings in the woods near their home. Elsie, who had been raised in South Africa, enclosed a print of one of the photographs in a letter to a friend in 1918, writing, “It is funny, I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there.” In 1919, the photographs gained the attention of Edward Gardner, a leading theosophist, after Elsie’s mother began attending meetings and sharing the images. Gardner sent the photographic negatives to a photography expert by the name of Harold Snelling to validate. Snelling corroborated that the negatives were genuine. Kodak was then enlisted into the investigation, and the company agreed that the images showed no signs of staging.

The images would cause their biggest hubbub the following year, in 1920, when Doyle, who was a spiritualist, published the photographs to illustrate a 1920 article on fairies he wrote for The Strand Magazine. Doyle believed the images to be factual evidence of psychic and paranormal phenomena. While some readers agreed, others argued that the images were a hoax. Though the cousins maintained that the photographs were real for many years, in 1983, Elsie and Frances admitted in an article that they’d staged the images—drawing the fairies and supporting them on hatpins—but maintained that they had indeed seen fairies on many occasions.

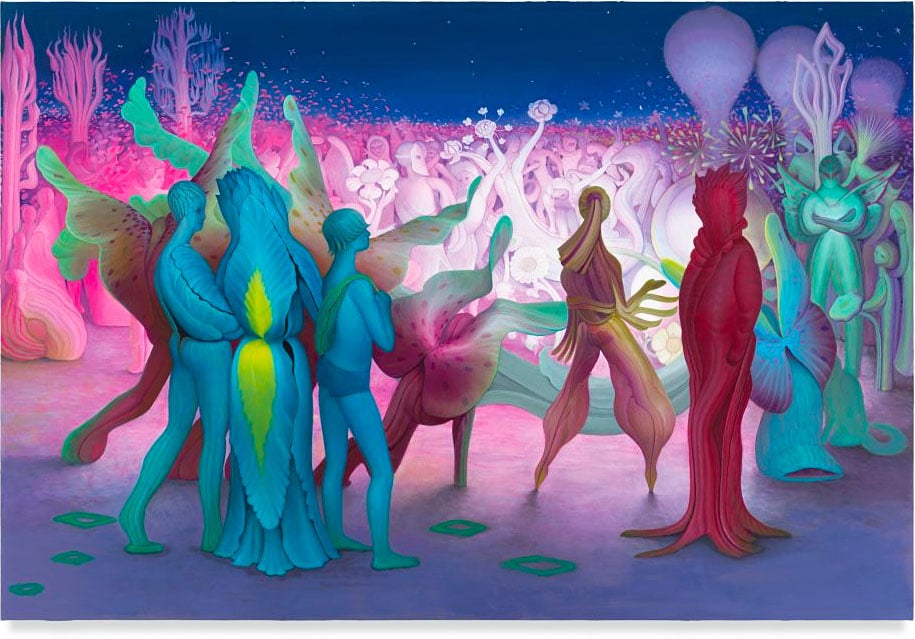

Inka Essenhigh, Rave Scene (2022). Courtesy of Miles McEnery Gallery.

While the popular fascination with fairies has waxed and waned over the decades, these petite pixies never fully vanish from the painted world, and a number of contemporary artists incorporate them into their visual lexicons. Artist Inka Essenghigh’s recent exhibition at New York’s Miles McEnery was replete with luscious, oversized flowers and yes, convivial circles of faires. Kiki Smith, whose works often mine the dark sides of fairytales, has alluded to the more sinister sides of fairy beings too, in works like Fairy Circles (1998), which pictures two witchy circles of bronze mushrooms, in the collection of the Broad Museum. Other artists engaging with the motif include Kate Klingbeil, Allison Katz, and the German photographer Kathrin Linkersdorff, whose current exhibition “Fairies” at Yossi Milo Gallery, explores the microcosmic world of flowers and their vast unseen—dare we say magical—systems.