The Louvre is hoping that a novel legal maneuver may help it shield its reputation in the ongoing international antiquities trafficking case that has ensnared its former director.

Following a first, unsuccessful effort, the Paris museum has made a second bid to be named a civil party in the case that has stunned the art world, with charges brought against the museum’s former director, Jean-Luc Martinez, for complicity in gang fraud and laundering of antiquities sold to the Louvre Abu Dhabi for some €50 million (around $53 million). The sprawling case involving U.S., European, and Middle Eastern parties, threatens to sully France’s esteemed, and heavily monetized, distinction as a leading global expert in the management and creation of museums. In fact, the Louvre is arguing that the damages have already been felt.

The institution first requested to be named a civil party in June 2022, citing harm suffered to its global reputation, its “national and international ranking, notably [concerning] partnerships concluded with foreign public and private institutions,” according to French reports, assertions echoed to Artnet News by a source close to the case. However, last summer, the presiding investigating magistrate at the time, Jean-Philippe Gentil, refused the Louvre’s request, citing “no current and personal prejudice,” suffered by the museum.

The Louvre’s good name is a national golden goose, with the clearest example being the Louvre Abu Dhabi, the result of a 2007 deal binding the United Arab Emirates into paying €1 billion in exchange for using the Louvre brand name, expertise, and art loans over 30 years. The deal was extended another 10 years in 2021.

The decisions to recommend the now suspect antiquities for acquisition by the Emirati museum were made between 2014 and 2018 by a scientific committee within the Agence France Muséums (AFM), a mixed private and public advisory group that worked with the Louvre and other French museums to develop the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which opened in 2017. Martinez headed the AFM committee while he directed the Louvre, which he helmed from 2013 to 2021.

The museum appealed the judge’s refusal to name it a civil party, and their plea was examined during a closed hearing earlier this month. In its arguments, the museum notably did not place any suspicion of wrongdoing on its former director, instead expressing confidence in his integrity. Throughout, Martinez’s lawyers have also insisted on his innocence and have appealed his indictment to the highest French court.

So why, then, would the Louvre ask to be named a civil party in the case against Martinez?

For starters, being named a civil party would give the Louvre access to evidence in the investigation that has already embroiled several of the museum’s working curators, who were questioned and released without charges. Were the Louvre to have such access, “that would absolutely be an advantage to be able to share that with other individuals within the organization, to be able to basically peer around the bend and see the legal strategy that the prosecuting, investigating judge may be using,” explained Dr. Derek Fincham, art and cultural heritage law professor at the South Texas College of Law Houston, speaking to Artnet News.

The legal expert effectively questioned the French investigating judge’s rejection of the museum’s initial bid to be named a civil party, which could be interpreted in different ways. On the one hand, he observed that whether it’s a “cognizable legal claim or not,” the Louvre’s reputation has indeed been “tarnished, based on these actions.” On the other hand, Fincham said that the judge might have refused to name the Louvre a civil party because he felt that it “may have been complicit in not asking the right questions, and not upholding the proper questions and procedures for acquiring new material.”

That said, it is important to understand that the institution itself has not actually been charged with wrongdoing. Art trafficking cases typically focus on individuals more directly linked to the initial theft and laundering. Being named a civil party would not entirely absolve the museum of fault, nor would it make the museum entirely a victim in this case. It would, however, affirm damage was done to the institution, permitting them to potentially seek compensation for an offense. “It’s a gray area,” where both can partly be true, Fincham said.

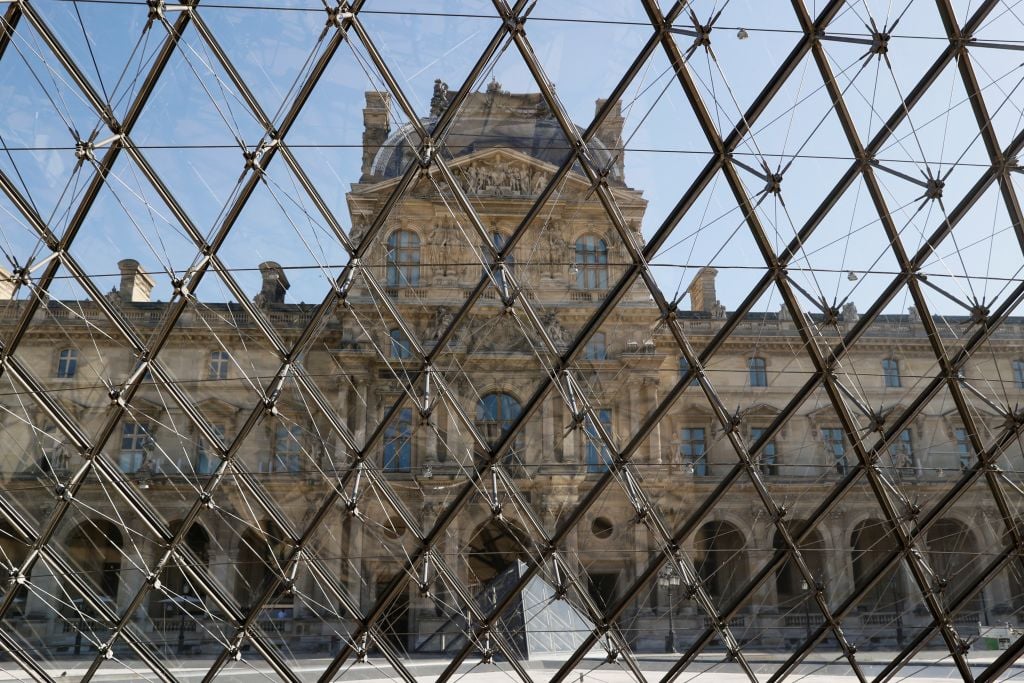

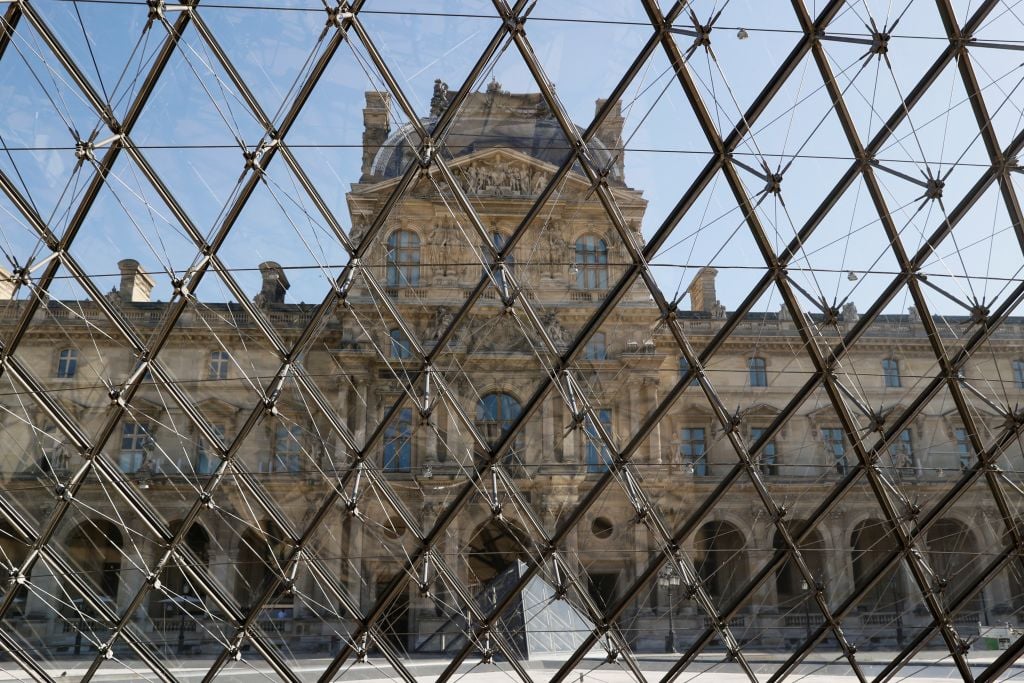

A picture taken on June 23, 2020 shows the Louvre pyramid by Chinese architect Ieoh Ming Pei, and the Louvre Museum in Paris. Photo by Thomas Samson/AFP via Getty Images.

One source close to the case maintains that the judge denied the Louvre’s first attempt to be named a civil party because approval would have undermined the charges against Jean-Luc Martinez. This is because his defense has asserted that Martinez was misled by fake provenance documents, while acting in good faith, effectively the same line being upheld by the museum. Naming the Louvre a civil party and victim of fraud, they argued, would contradict the judge’s decision to charge Martinez with complicity in connection to the same fake documents.

Without having access to the judge’s full explanation for his decision, Fincham agreed such a reading “certainly checks out.” The Louvre and its legal representative declined to comment.

Still, the defense that a person embroiled in a looted art case was misled by someone further down the chain of events, “is the argument that everyone who has acquired stolen art or stolen objects, makes,” said Fincham. The law requires that thorough interrogations are made into an object’s pedigree, and that origin documents are not to be taken merely at face value, he added. Historically, when it has come to the sale of antiquities, many documents “were obviously fake, but many buyers chose not to ask reasonable questions, and that’s how this looted material ends up in collections,” he said. Were a prosecution against leading decision-makers of acquisitions—including museum workers—to be successful, Fincham said it “may break the dam for this kind of wrongdoing,” likely leading to prosecution of other individuals. “That kind of high-level responsibility is yet to emerge,” he added.

Whether the provenance of these objects was properly probed, and who exactly was responsible for their sign off, will be examined next month, when Martinez and a fellow curator from AFM, Jean-Francois Charnier, also charged with facilitating the acquisitions despite what investigators allege as known concerns related to their provenance, will appeal their indictments to France’s highest court. Their defenses have separately argued the curators used high standards, beyond common protocol, in leading the vetting and recommendation for purchase of the antiquities, and that they were not personally responsible for directly authenticating documents. Instead, provenance research was carried out by other qualified experts including, but not limited to, other Louvre staff.

The fact that the general prosecutor had recommended charges be dropped against Martinez and Charnier—a view that was rejected by an appeals court which maintained the charges—could nevertheless help the defense going forward. “It signals that the legal theory for prosecution rests on a very narrow margin for error,” and “would theoretically prove the basis for future defenses,” said Fincham.

Whatever the outcome, it is clear that it is not only the Louvre that has a lot at stake here, and the result of the case will be closely watched by the international museum community.

More Trending Stories:

French Authorities Investigate Sale of Notre Dame Stained Glass by Sotheby’s After a Heritage Group Alleges It Was Stolen

John Baldessari’s Heirs Are Caught Up in a Tangle of Litigation Over the Care and Ownership of the Late Conceptual Artist’s Works

A Museum Loaned an Artist $72,000 to Make a Sculpture. Instead, He Delivered Two Empty Frames and Refuses to Return the Money

Albrecht Dürer Painted Himself Into a 16th-Century Altarpiece to Spite a Patron Who Paid Him Poorly, New Research Suggests

Two A.I. Models Set Out to Authenticate a Raphael Painting and Got Different Results, Casting Doubt on the Technology’s Future

Freud, Hockney, Pigeons, and Pubs. Step Inside the Eccentric New London Art Show Curated by Designer Jonathan Anderson