Read Part 1 and Part 2 of “‘Foreigners Everywhere,’ Unpacked,” here and here.

Brazilians Everywhere

Does Adriano Pedrosa’s Venice Biennale represent a new view of global art seen from below, based around a shared perspective of “how it felt to be there, on the bottom, looking up at the descending heel,” as Salmon Rushdie wrote of a solidarity trip he took to Nicaragua in the ‘80s? Or does it in fact represent something more privileged, a cultural tendency whose project is to “sell indulgences of political emotion to the middle class”—Roberto Schwartz’s diagnosis of a certain self-deluding tendency in Brazilian art?

There is actually a way to look at this show through both lenses at once, without trying to smooth over their differences. This is through the recently popular concept of “Brazilianization.”

The idea, in essence, is this: Globalization was once assumed to be a story that flowed in one direction, with the “developing” countries of the Global South converging on the living standards, consumer lifestyle, and stable liberal norms associated with the “developed” ones, a process sometimes called “Americanization” (arrogantly, to many Latin American observers). In the long wake of the 2008 financial crisis, and even more so with the havoc of the pandemic, this does not seem to be the path we are now on, either economically or politically.

The “Nucleo Storico: Portraits” gallery. Photo by Ben Davis.

Instead, as theorist Alex Hochuli wrote in “The Brazilianization of the World,” the 2021 essay that popularized the concept, “the Global North… is demonstrating many of the features that have plagued the Global South: not just inequality and informalization of work, but increasingly venal elites, political volatility, and social ungluing.” (One of the Hollywood hits of 2024, Alex Garland’s very bad Civil War, is more or less the liberal imagination grappling with this reality, centering on U.S. photojournalists who once captured atrocities ‘over there’ now witnessing them ‘over here.’)

Why “Brazilianization” in particular? Partly because Brazil is a middle-income country. The framework is not just about poverty or corruption, but about the proximity of extreme wealth to deprivation—the condition symbolized by images of ultra-luxury high rises overlooking favelas in Brazil’s big cities. Also key is Brazil’s historic self-identification as “Country of the Future,” its sense that its size and resources promised a destiny that has been continuously thwarted. That makes it useful to look to for perspective as Europe and North America deal with the psychic fallout as their own national narratives are no longer carrying them toward an expected better future.

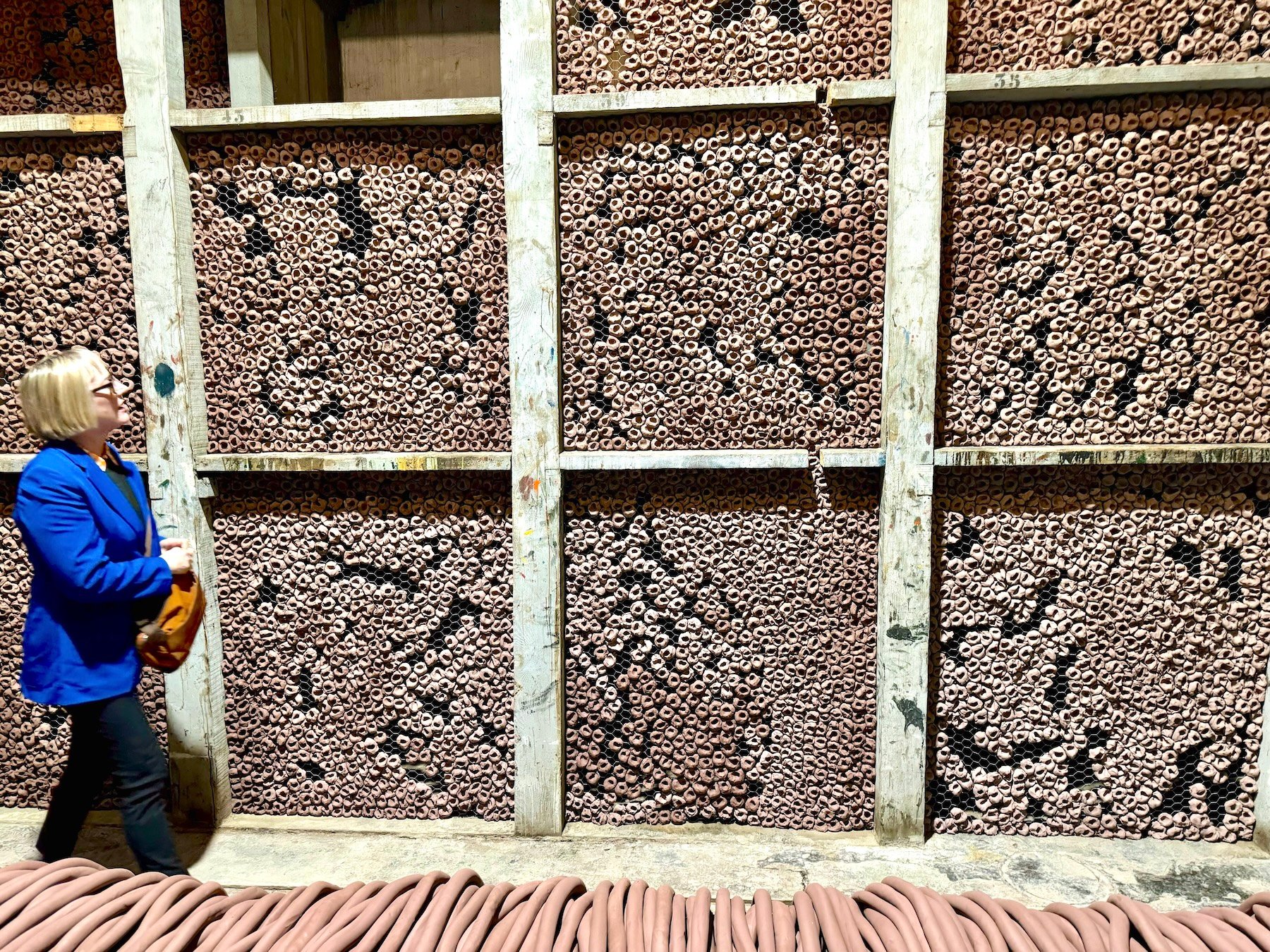

Mataaho Collective, Takapau (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

I should stress: It’s not a matter of racist rhetoric about “becoming a banana republic” or “looking like the Third World” or some such. The idea is that the Global North has something to learn from Brazilian experience—not just about a benighted other, but about itself. “Brazil’s consciousness of its own promise, and consequent frustration, has prompted the development of a critical perspective on modernization that the world would do well to study,” Hochuli writes.

What might the “Brazilianization” thesis make us reckon with, when it comes to the audience for global contemporary art? Two things.

Cynicism

Culturally, Hochuli connects the concept to an epidemic cynicism, fostered by the mismatch of classical liberal rhetoric about a free and fair marketplace of ideas and the reality of a world actually defined by extreme hierarchy and inaccessible institutions. And, indeed, the last decade has seen dramatic challenges to art’s image as a space of ideals. Everywhere, museums and art institutions have been hit by wave upon wave of protest.

On the one hand, there has been a long-overdue reckoning with representation, inspired by movements like Black Lives Matter and MeToo. On the other, art institutions have faced protests over their connections to extreme wealth and their role in “artwashing” the reputations of unsavory corporations, governments, and plutocrats.

These two lines of critique can flow together: One reason that art history has been biased is because it is greatly shaped by a limited set of powerful people, who are not at all demographically representative of the world. But they can also clash: The very definition of “artwashing” is powerful people using art patronage to create a more tolerant, forward-looking image for themselves.

Might the “critical perspective on modernization” from Brazil sharpen sensitivity to the latter contradiction? In the late ’60s, famed Brazilian artist Hélio Oiticica saw the rebel countercultural energy of the Tropicália movement, to which he had given the name, defanged by the Brazilian dictatorship. Anguished by that reality and living in exile, Oiticica would in turn be an early critic of the cooption of queer culture. He slammed New York’s cool crowd for “feeling like they are allies of the marginal” when they were “just raising marginal activity to a bourgeois level”—that is, turning it into an object of exotic consumption.

The section of the Biennale dedicated to “The Disobedience Archive,” a collection of videos about art and activism. Photo by Ben Davis.

The so-far overwhelmingly dismissive critical reaction to the 2024 Venice Biennale has basically been that it is just another identity-obsessed “woke” biennial. I’d argue that the best way to understand the monomaniacal emphasis on marginality, in this Biennale and elsewhere, is that it has a negative role as well as a positive one; it is compensatory as well as affirmative. It is a symptom of the fact that the whole system of art consumption and display otherwise feels itself deeply vulnerable to all kinds of other criticisms about its entanglement with wealth and power, in very fraught times. Any let-up on reminding you that you have an ethical duty to like what is in front of you threatens to let all that flood back in.

Ultimately, the transformation of marginality into the sole grounds of inclusion doesn’t even best serve the marginalized. It all but demands observers think of the selection only through the lens of identity, immediately summoning the specter of tokenization (Nicolas Bourriaud’s diagnosis of this show: “what the artist is becomes more important than what they produce.”) The universal cynicism that Hochuli sees as taking hold means that “we mistrust ideals, holding them to be always ideological; that is, concealing selfish interests.” Alienation from apolitical aesthetics as privileged is simply displaced onto alienation about progressive “virtue signaling” as privileged.

Yinka Shonibare, Refugee Astronaut VIII (2024). Photo by Ben Davis.

Art historian Shifra Goldman long ago described how scholars of Latin American culture had learned to cast a jaded eye on “the pluralism which camouflages itself behind an egalitarian mask while it neutralizes class conflict (which has not abated) and the claims of new social movements.” More recently, the philosopher Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò’s idea of “elite capture” has received quite a bit of attention, specifically as a way to talk about the problems with certain forms of identity politics. I like the line Táíwò walks, helping us avoid a sterile “woke”/”anti-woke” polarization. He distinguishes between “identity politics” as the idea that some groups might have important shared experiences to draw on as political actors—obviously true—and a version of “identity politics” that gets captured by the wealthy and the connected.

Crucially, Táíwò actually drew the concept of “elite capture” from studies of developing economies (originally, the term described how corrupt elites “capture” foreign aid, turning what should benefit all into a form of patronage that they can distribute to cronies). “Multiethnic Global South societies easily fall into cycles of expecting elites to allocate resources along blatantly ethnic and regional lines,” he writes. “After all, the thinking goes, the elites of every other ethnic group will do the same when they’re in power.”

It is very bad if international art becomes widely viewed through this image of zero-sum “identity politics,” associating some very important things—Indigenous art, queer art, global art histories—with a new language of power and exclusivity.

Which brings me to my second theme…

Isolation

A key aspect of the experience of Latin American artists, Ecuadorian critic Jorge Enrique Adoum once argued, was the feeling of isolation in societies defined by intense stratification. (“Our group wasn’t very popular,” Lygia Clark once remembered, “as it was a group of intellectual artists who had no contact with the people.”)

Of course, in the Global North too, art has always been a bit at a remove from truly “popular” opinion—but in light of the “Brazilianization” thesis, it feels more and more important to make visible what Enrique Adoum called the “cage bars of reality,” the limits of the cultural space that you are in.

Lydia Ourahmane, 21 Boulevard Mustapha Benboulaid (entrance) (1901-2021) in the foreground, with Daniel Otero Torres, Aguacero (2024) in the background. Photo by Ben Davis.

One of the most important texts about art to me (I have an essay about it in my last book) is Roberto Schwartz’s “Culture and Politics in Brazil (1964–1969).” There, he describes with acuity the strange scene after the 1964 U.S.-approved rightwing coup in Brazil. Art production in those years of the dictatorship, he says, was surprisingly radical and left wing, full of inventive protests against a reactionary government and avowals of solidarity for the oppressed masses. In Schwartz’s analysis, this culture seemed to construct a compensatory, self-contained world, strangely cut off from the reality of brutal political defeat and failing to brace for the soon-to-arrive intensification of repression, the “coup within a coup” that hit Brazil in late ’68.

I see a similar pattern in the ideas that run through “Foreigners Everywhere” and other such shows—the creation of a heroic bubble that cannot see itself as a bubble, a cultural politics that views itself as a form of popular activism but that is about avoiding the political reality of being more and more isolated.

The clear difference between the Brazil Schwartz describes and today’s contemporary-art mainstream is that the intellectual culture of ‘60s Brazil put much, much more at stake. As Schwartz shows in his intricate analysis, isolated though they were, Brazilian artists and intellectuals inherited a robust (if too-institutional) type of developmentalist Marxism and a nervy anti-imperialism—the very climate of Latin American leftism that U.S. saw as threatening enough to greenlight a military coup to extinguish.

Watching a video in Pablo Delano’s “Museum of the Old Colony” room in “Foreigners Everywhere.” Photo by Ben Davis.

By contrast, the cultural politics that have captured the peaks of the global art establishment in 2024 have been shaped by a very different set of forces: the erratic, explosive, unresolved period of activism that began in the early 2010s, the period that São Paulo-based political thinker Vincent Bevins describes as “the mass protest decade.”

As Bevins shows in his 2023 book If We Burn, this period was characterized globally—in Brazil and Turkey and Hong Kong and even in the United States of Occupy, BLM, NoDAPL, and Bernie—by cataclysmic spikes of viral popular protest that tended to have huge and galvanizing temporary resonance, but that left behind little in the way of enduring organization. As a result, Bevins argues, more organized conservative forces have benefited most from the turbulence, have radicalized, and have grown closer and closer to power. Meanwhile, the institutions of a liberal establishment have been forced to adopt some radical phrases and symbolism, but very little else of deep substance.

Neon work by Claire Fontaine. Photo by Ben Davis.

And so, what you get is something like “Foreigners Everywhere,” exemplary of a global contemporary art discourse defined by a deep sense of the need to symbolize progress but that also doesn’t seem to believe in progress at all, turning away from the present. It is a show that is permeated in every part by anxieties about global reactionary politics, but that placidly assumes that its global audience is on board with progressive values.

There is art to like in it. There are aspects of its intellectual program that I think are truly important. At the start, I said that I think Pedrosa’s exhibition will be remembered positively.

I guess I’d qualify that by adding the words “in the future I would like to see.” Taking stock of how the show fits its many parts together also suggests to me that this future is being built on a fragile foundation.