It’s a gentle opening to the fifth edition of “Greater New York,” MoMA PS1’s survey show of art made by people living and working in New York City. This edition, like the previous, expands beyond contemporary-art trendspotting, with a notable number of reconsiderations or rediscoveries of dead artists, lending thematic heft and gravitas. Taking up two floors, with two additional video installations tucked away in the basement, “Greater New York” unfolds slowly for a show featuring a barrage of more than 200 works. That’s a result of the thoughtful, sensitive curation, led this year by Ruba Katrib.

In one of the first galleries on the second floor, stylized and textured paintings of flora by Nadia Ayari echo the colors of adjacent photographs by Avijit Halder. Halder’s work is self-referential and autobiographical: men wrap themselves and wave around saris that once belonged to the artist’s mother, who died violently in a Kolkata brothel, we learn from a wall text. The saris, which Halder carried with him from India to the U.S. after his mother’s death, flounce and billow, wrap around the bodies of Halder and others, all in an exploration of gender, its performance, and Halder’s non-binary identity. The photographs also exorcise grief and commemorate his mother’s life.

The work could rely entirely on these autobiographical details, except that the photographs are also gorgeous: the rich colors of the saris, the slight overexposure of some of the frames, the precise composition. Nearby, Ayari’s paintings, with their similarly rich textures and bright blues, pinks, and greens, hang close, as if to say about Halder: this is an artist making art, not just someone telling a sad story. It’s a useful reminder, and one which takes time—time in the room, time with the paintings, time with the photographs—to fully receive.

Avijit Halder, Birth (2018) in “Greater New York.” Photo by Ben Davis.

Personal narrative, autobiography, and self-reference abound in contemporary art practices, and stories of personal struggle and strife seem almost necessary to lend a piece of art the requisite gravitas to hang at a museum. It’s not that there’s none of this in “Greater New York”—in fact, there’s plenty—but the works don’t rely on the struggles that it took to produce them to make a claim to artistic substance.

Themes follow viewers around like friendly ghosts, giving the entire show a sense of casual cohesion. The AIDS crisis and queer life in the New York City of the ’70s and ’80s appear directly in many artists’ biographies, but also more subtly in certain pieces, like Rotimi Fani-Kayode’s Maternal Milk, a black-and-white photograph of a Black man sitting on the ground hunched over himself as a white milky liquid streams onto his back, and in Andreas Sterzing’s photographs of artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz, painter and sculptor Luis Frangella (who died of AIDS-related complications in 1990), and conceptual artist Mike Bidlo.

Luis Frangella, David Wojnarowicz (1984). Photo by Ben Davis.

Frangella’s paintings also appear dotted throughout the third floor, a huge portrait of someone unnamed in the main gallery echoed later by a challenging portrait of Wojnarowicz, in which a broad-strokes representation of the artist’s face appears on either side of a piece of cardboard folded into a tent shape. The connections are noticeable but not didactic, making room for viewers to trace them themselves.

In that same large third-floor gallery, a two-minute video produced by poet Bob Holman

for Poetry Spots, a series of short videos that ran between segments on WNYC-TV from 1987 to 1995, features Diane Burns reciting her poem “Alphabet City Serenade.” Burns, of Chemehuevi and Anishinaabe origin, recites lines like “I’m American royalty / walking around with a hole in my knee” and “I’m a hopeful Aborigine / trying to find a place to be” in a sing-songy voice over footage of the East Village and Lower East Side.

With 30 seconds of the clip to go, she appears in front of the camera, looking directly into the lens as her voice changes from sing-songy to declarative:

Do you know that I hate Doris Day?

I hate Chevrolet.

I hate Norman Bates.

I hate the United States.

The piece’s last line lands poignantly in our present-day context:

Oh, you wanna talk about gentrification?

Burns’s video is not her only work on display, but it’s the most inescapable, its looped sound filling the third-floor gallery and echoing other pieces that also deal with indigeneity and systemic mistreatment of Native Americans by the United States government, such as G. Peter Jemison’s mixed-media works, which incorporate objects of personal and cultural significance: paper bags, parasols, treaty cloth, calico beads.

Throughout “Greater New York,” pieces that speak to similar themes cut across time and geography, as well as across gallery space, highlighting the larger contexts that make individual works resonate regardless of when they’re viewed.

Works by G. Peter Jemison in “Greater New York.” Photo by Ben Davis.

In one of the show’s quiet highlights, on the wall adjacent to Poetry Spots, Yuji Agematsu’s work zip: 01.01.20 … 12.31.20, 2020 displays found objects arranged inside of 366 cigarette carton cellophane wrappers, one for each day of the year 2020.

Here’s an enormous wad of yellowed gum leaning on a small piece of glass, here’s a small pink rosebud drying next to some debris, here’s a loop of embroidery floss stained with who-knows-what, here’s a cinnamon stick. It’s not the fact of their having been collected, nor even the fact that they were acquired over the course of the pandemic, nor even the diligence that it took to collect and arrange these items every day over a year, that makes this art. It’s these tiny sculptures’ purposeful arrangement, each cellophane wrapper containing a careful composition. Take out one item, and it becomes trash once again.

Artwork by Kristi Cavataro in “Greater New York.” Photo by Ben Davis.

In “Greater New York,” the context of the physical city appears at once indirect and indispensable to the artists’ practice. A pair of recent sculptures by Kristi Cavataro are a case in point. Their soldered, colored stained-glass pieces are formed into shapes that call to mind city infrastructure—light posts, street grates, wrought-iron bars over windows. Here’s New York City again, the pieces say, in seemingly infinite forms.

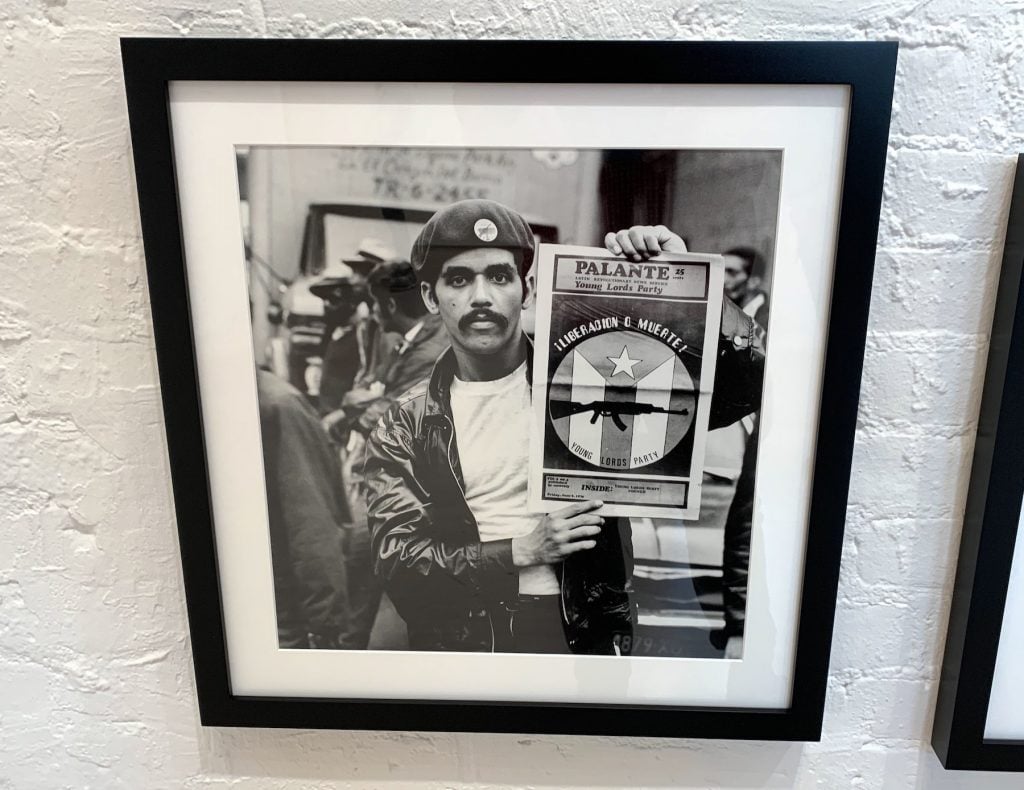

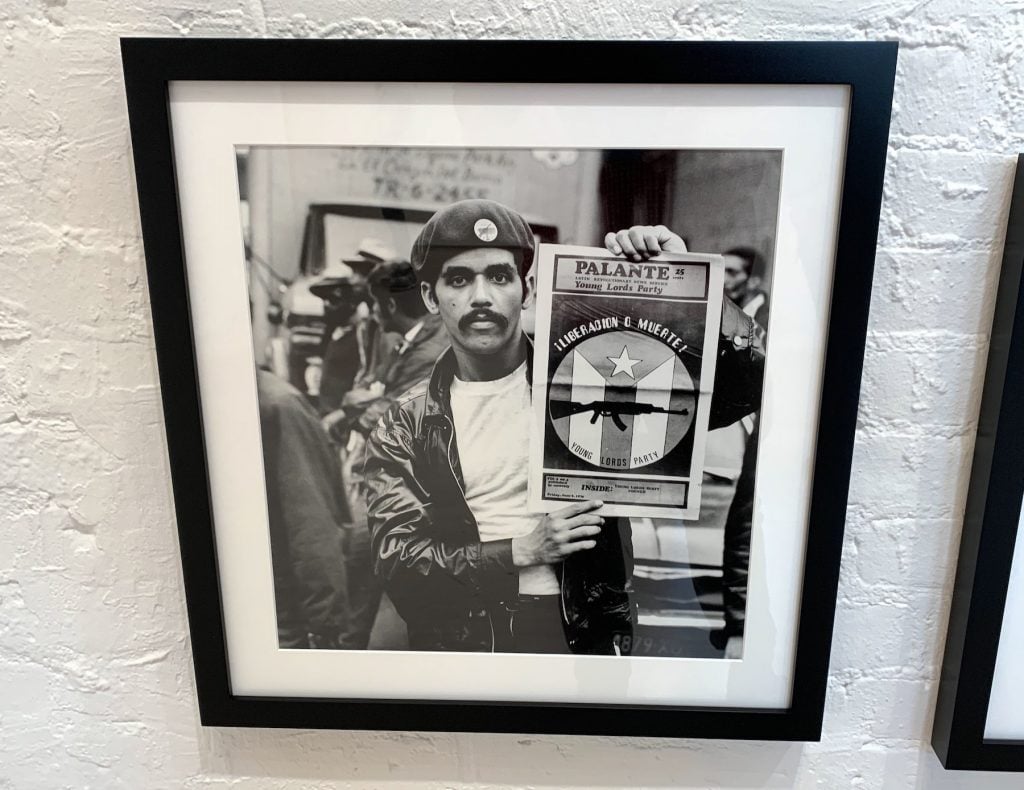

Partly, this is owed to their placement near photos by Hiram Maristany, who served as the official documentarian for the New York chapter of the Young Lords Party. A wall of his work from throughout the 1960s highlights dynamic action in the streets via close-ups of jackets bristling with political pins, or a group of protesters taking over a truck emblazoned with the words CHEST X-RAY UNIT, or a group of young women sitting on the steps.

Photo by Hiram Maristany in “Greater New York.” Photo by Ben Davis.

It’s a relief to see pieces that play well with each other, both thematically and aesthetically. And while all the themes we’d expect from a survey show of this size and scope are here, they don’t beat viewers over the head. Works on display often feel personal, in a way that makes them resonate widely without losing well-wrought specificity. Frangella’s paintings, for example, are as much about the AIDS crisis and queer life in New York City as they are about broader themes like grief, loss, and the inevitability of both friendship and death. The work’s recurrence throughout the galleries nudges us to ask who we tie ourselves to and why we do that tying.

It’s a vast show, so these thematic touchpoints—which take the form of Frangella’s paintings, or Cavataro’s sculptures when they appear again on the third floor—give viewers a sense of orientation and a set of throughlines to follow as they make their way. The curation uses the galleries’ varying sizes effectively, larger rooms presenting an almost dizzying variety while smaller rooms hew closer to a single conceptual or aesthetic theme.

Drawings by Rosemary Mayer in “Greater New York.” Photo by Ben Davis.

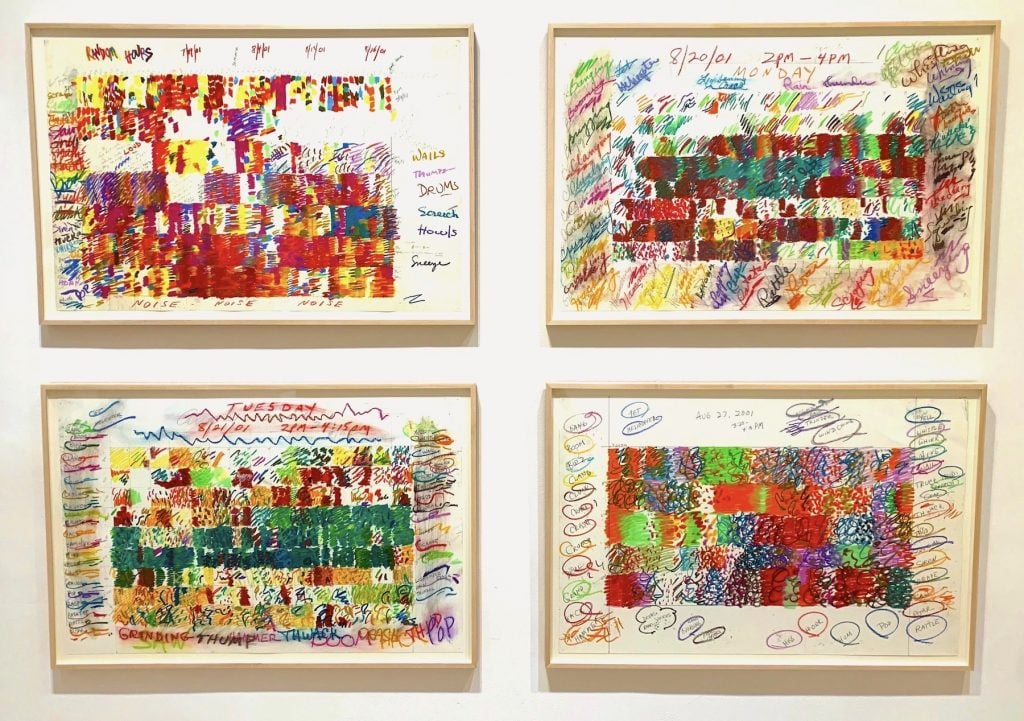

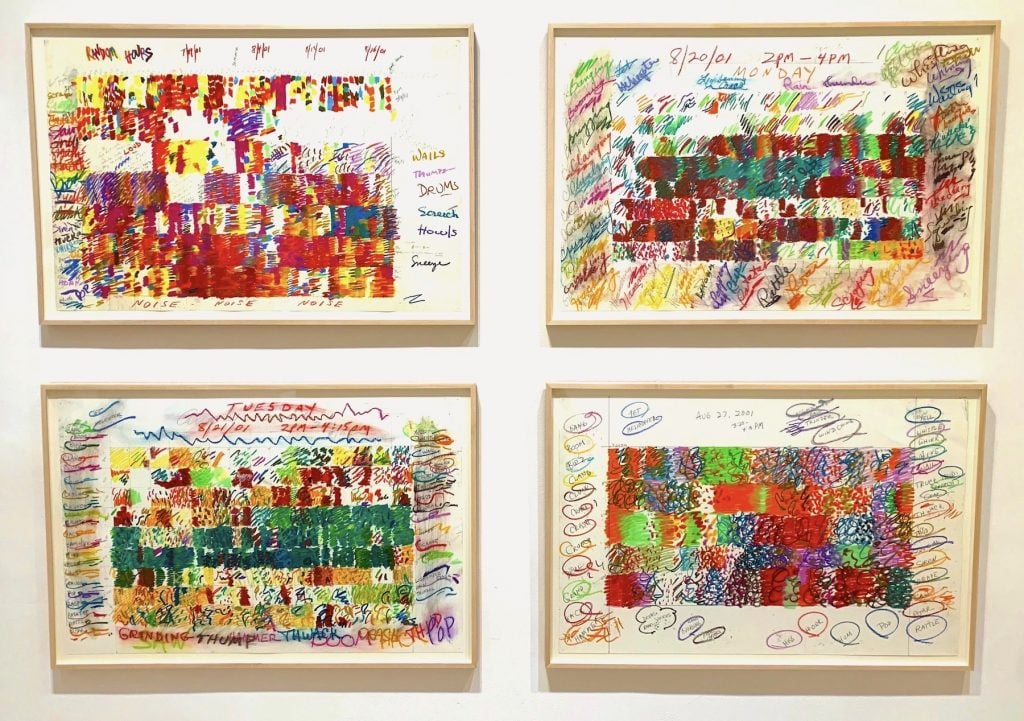

A favorite in the latter category comes in a small gallery on the third floor, where drawings by Milford Graves diagramming his research into the effect of sound and music on the human body hang across from a set of four works by Rosemary Mayer that track the noises heard by the artist over different spans of time. Each of Mayer’s colorful pastel diagrams is casually keyed on the papers’ margins—she either circles or writes the name of the noise in a corresponding color—bang circled in magenta, clanging in a cursive coral, an ochre wails, a purple siren. The works, which are a result of Mayer’s listening for as long as a month and as little as 15 minutes, serve as a testament to just how much a single New York Minute can contain.

That sense of the city’s depths, of forever-spreading chaos to wade through, acts as both context and fodder for the artists whose work is on view throughout this show. There is so much to take from the everyday that the artist’s responsibility becomes giving it order, arranging it, making it make sense. The exciting belief that seems to underlie this year’s “Greater New York” is that a viewer could do the same.

“Greater New York” is on view at MoMA PS1, Queens, through April 18, 2022.