Art & Exhibitions

Christian Viveros-Fauné on Why Greater New York Signals the Start of a New Confusion

It’s time to redefine cultural and political alienation in the city.

It’s time to redefine cultural and political alienation in the city.

Christian Viveros-Fauné

What does it mean when MoMA PS1’s “Greater New York,” the city’s premiere youthennial calls it quits on being a showcase for emerging artists and turns to its own history to condemn gentrification, apolitical art and the art market? Among other things, it signals that certain unresolved ideas have gained a foothold among museum curators.

On entering this year’s exhibition, one might be forgiven for thinking the tide has turned on runaway real estate speculation and rampant commercialism in the arts. Then one looks at the average age of the exhibition’s 157 artists and the production dates for its more than 400 objects: Nearly half of the exhibition’s works were made before the millennium by artists who are 48 or older.

According to the ancient Egyptians, the ouroboros, the ancient figure of a snake devouring its own tail, signals both self-reflexivity and cyclicality. Until March 7, 2016, the date “Greater New York” closes, there will be no better illustration of this self-devouring symbol than MoMA PS1’s display of old and new experimental artworks.

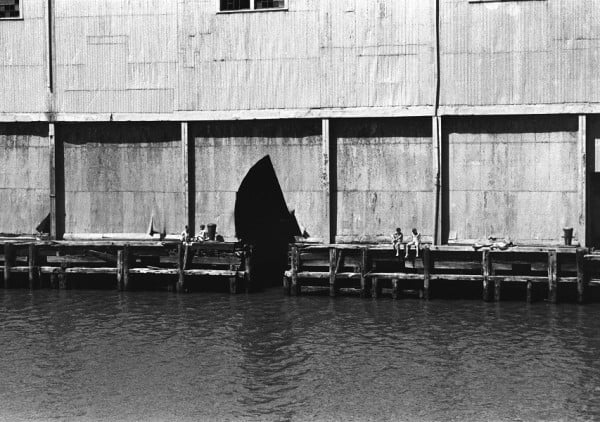

Lutz Bacher, Magic Mountain (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1.

Since PS1, a forty-four year old institution, joined MoMA in 2000, it has lost a great deal of its bootstrapping, cutting-edge identity. Today, even its Volkswagen sponsorship seems like a 1980s throwback. In a climate in which the average Manhattan apartment costs $1 million, disgraced corporate connections do little to foster an image of cultural renewal.

No wonder, then, that the fourth iteration of “Greater New York” appears so steeped in nostalgia for what the show’s organizers—curator Peter Eleey, art historian Douglas Crimp, associate curator Thomas J. Lax, and assistant curator Mia Locks—correctly argue was a much simpler time. The exhibition press release not only praises the 1970s and 80s as a period in which “experimental practices and attitudes” flourished, it also prominently features a number of lesser-known artists from the era. The organizers’ message is clear: Today’s emerging artists largely epitomize the status quo; select under the radar artists (one could call them “submerging artists”), on the other hand, represent living models of creative resistance.

Alvin Baltrop, The Piers (With couple engaged in sex act) (1975-86).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1.

This spirit of reclamation certainly appears to have inspired the inclusion of 30 Alvin Baltrop photographs of gay life on the West Side piers. Black-and-white views of male sexual encounters set amid the city’s crumbling infrastructure in the 1970s and 80s, Baltrop’s modest-sized images set the tone for the sexual politics that dominate the building’s first floor galleries (one image featuring Gordon Matta-Clark’s sliced up warehouse, “Day’s End,” pictures his infamous architectural intervention as a violent gash). Elsewhere, videos of drag queens and club kids captured by the late Nelson Sullivan underscore the passing of New York’s once thriving nightlife community. A few rooms away, Rosalind Fox Solomon’s 1990s photo-documentary of AIDS-affected families hits an activist note repeated in works by painter Donald Moffett and the lesbian collective Fierce Pussy.

Rosalind Fox Solomon, Liberty Scaffolded (1976).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1.

The feeling of 2015’s “Greater New York” being a period show about art in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s abates—somewhat—on the exhibition’s second floor, where one of the museum’s largest galleries is given over to a celebration of the human figure. Two sculptural trompe l’oeil nudes, one male the other female, by provocateur Tony Matelli are literally stood on their heads; Elizabeth Jaeger’s sculpture of a copulating couple gives swooning shape to sexual intimacy; a bronze idol anthropomorph by Huma Bhabha depicts a 21st century Frankenstein. Still, like elsewhere in the exhibition, Gen Xers, Baby Boomers, and even members of the Greatest Generation set the agenda for artists belonging to generations Y and Z. Next to these lively post-millennial works totter many more hominids produced by veteran artists Judith Shea, John Ahearn, Ugo Rondinone, Red Grooms, Kiki Smith, and Mary Beth Edelson.

Amy Brener, Dressing Room (2015).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1.

But two late artists, above all, dominate the faltering premises that animate this graying iteration of the old youthquake exhibition (the show recurs every five years). There are three photos by Gordon Matta-Clark that document the original “structural cuts” the artist made to MoMA PS1’s building for its 1976 inaugural exhibition (the institution was then simply called PS1). And then there are Henry Flynt’s 57 snapshots of 1970s “SAMO©” graffiti, made by the real-life Jean-Michel Basquiat—which include the acerbic tags “SAMO© for the so-called avant-garde” and “SAMO© is dead.” Works that harken back to the 1971 founding of PS1 as the Institute for Art and Urban Resources Inc.—then an organization whose primary mission was to turn abandoned New York City buildings into artist studios—their inclusions read like elegies to a golden era. That was a time when crime was rampant, real estate speculation embryonic, and artists freely transmogrified into the original culture industry canaries.

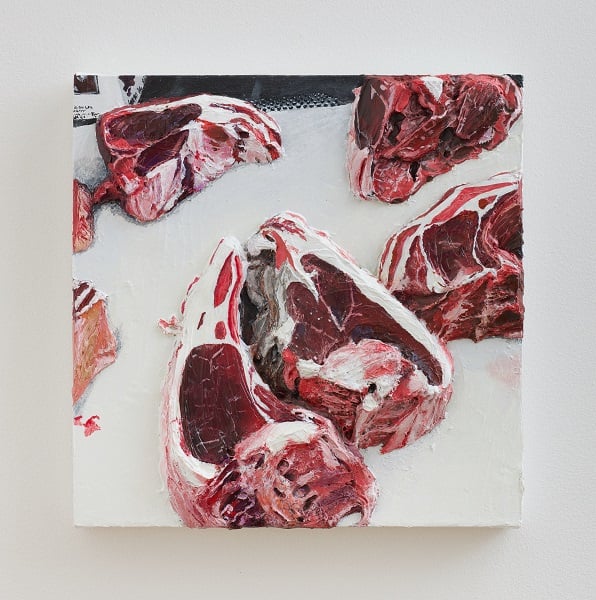

Gina Beavers, Local White Dorper Lamb (2013).

Image: Courtesy of the artist and MoMA PS1.

Which is not to say that, despite its faults, this year’s “Greater New York” is not without its merits. Among the show’s strengths are its redefinition of the idea of the emerging artist as an ageless concept, as well as its inclusion of a clutch of terrific younger creators, among them the painter William Villalongo, photographers Sara Cwynar and Deana Lawson, installation artists Angie Keefer and Cameron Rowland, and sculptors Amy Brener and Raúl de Nieves. But 2015’s “Greater New York” also signals the beginning of a new set of confusions. If institutions like MoMA PS1 are clued in to New York’s artistic decline, it’s time to redefine cultural and political alienation in the city—one museum experience at a time.