Crime

The Feds Indict Two Detroit Brothers and a Florida Man in a Long-Running Forgery Scheme Peddling Fake Art and Sports Memorabilia

The men hawked works by purportedly by Gertrude Abercrombie, George Ault, and others from 2005 to 2020.

The men hawked works by purportedly by Gertrude Abercrombie, George Ault, and others from 2005 to 2020.

Eileen Kinsella

The Department of Justice has indicted three men in a massive fraud and forgery ring that duped well-known auction houses across the United States. As it turns out, the sting had been a long time coming.

Two brothers from Michigan, Donald Henkel and Mark Henkel, along with a Florida man, Raymond Paparella, were charged with applying false autographs and signatures to paintings and sports memorabilia, which they later sold for profit. The scheme allegedly lasted from 2005 to 2020.

According to a press release and the accompanying 34-page indictment from the DOJ’s Chicago office, Donald Henkel created or altered many of the works in a large barn on his property in Northern Michigan—one report dubbed it a “forgery factory”—that was raided by the FBI almost two years ago, in the summer of 2020.

Some of the fake paintings—purported to be by well-known American modernist painters including George Ault, Ralston Crawford, and Gertrude Abercrombie—went on to sell for more than $300,000 each at auction.

It is unclear if the men have been arrested or are in custody. The DOJ did not respond to a request for comment. The defendants have all pleaded not guilty to the charges, according to the statement.

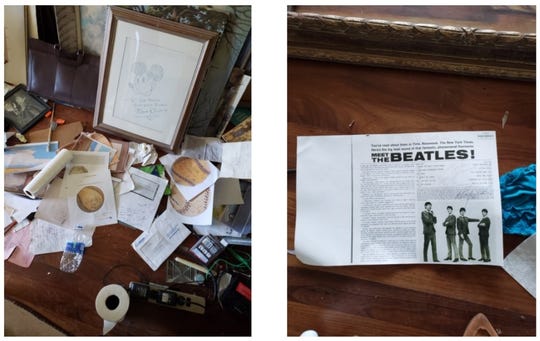

The FBI raid at the home of DB Henkel turned up purported memorabilia including a Mickey Mouse drawing with a Walt Disney signature and an advertisement for the Beatles. Photo courtesy of the FBI.

Paparella is described as an alleged “straw seller” who schemed to conceal the Henkels’ involvement with the items in an effort to pass them off as genuine. In addition to the art, fake sports memorabilia on offer included baseballs and bats purportedly signed by stars including Lou Gehrig, Babe Ruth, Honus Wagner, and Cy Young.

The indictment points to several unnamed “victims” including auction houses in Chicago, Dallas, Pennsylvania, London, and New York. Also affected were galleries in Grand Rapids, Michigan; New York City; Hudson, New York; and a collector in California.

Among the works identified as part of the criminal activity was Coming Home, a work purported to be by Gertrude Abercrombie and dated 1947. According to the Artnet Price Database, the work sold at Hindman Auctions in Chicago in May 2019 for $93,750, making it the eighth most expensive auction price for the artist. (Abercrombie’s market has been on a steady incline of late, with four of her top 10 auction prices set this year.)

Three works purported to be by George Ault also appear to have sold at Hindman between 2018 and 2019 for as much as $372,500 each.

Henkel and Paparella tried unsuccessfully to sell a number of other works listed in the indictment, including one supposedly by Ault called Burghal Barber. Three separate buyers declined it; one believed the work was “fabricated,” according to the indictment.

The duo also failed to sell two works purportedly by Ralston Crawford, though one work—Smith Silo, Exton, dated 1936–37—sold for $395,000 at Hindman in May 2016.

Hindman declined to comment on any of the sales.

A representative for Upper East Side gallery Hirschl & Adler confirmed earlier reports that it was taken in by the scam when it spent $709,000 at Hindman for two of the purported Ault works: Morning in Brooklyn and Stacks Up 1st Ave. The gallery returned them to Hindman but did not comment on whether they were refunded. The FBI reportedly believes Morning in Brooklyn was consigned by a Henkel conspirator in Virginia.

Although the indictment names just three people, it also includes five unnamed “co-schemers” in states across the country including California, Michigan, Virginia, and Florida.

FBI agents reportedly discovered the forgeries after learning that the type of paint used in one work purportedly by Ault did not exist at the time of the artwork’s supposed creation almost a century ago.

The unidentified victim, who paid $200,000 for the work, became concerned after being unable to find any trace of it in the artist’s archives. A conservator who examined the piece believed the painting was made in acrylic paint, which only became commercially available in the 1950s. Ault died in 1948.