Opinion

Inside the NFT Rush: Crypto-Art Promises to Transform the Whole World—But Throw Some Totally Dope Parties First

In the fourth article in our series, we enter the Dreamverse.

In the fourth article in our series, we enter the Dreamverse.

Ben Davis

This article is the fourth of a series about NFT.NYC and the culture surrounding NFTs. Read Part 1, Part 2, and Part 3 here.

On the second day of the NFT.NYC conference, the artist Xi Li speaks on a panel about “New Models of Artist Empowerment.” She waxes rhapsodic about the new creativity economy: “When I saw Ready Player One, I just wanted it to come true!”

She is referring to Steven Spielberg’s 2018 movie about a future dystopia where civilization has collapsed into misery, with the only hope of deliverance coming from a scavenger hunt in a corporate-controlled VR world dominated by recycled pop culture.

“You cannot deny it. Don’t resist the technology,” Li continues, in evangelist mode. “Don’t look at the details.”

What a vision of artist empowerment!

In response to the many anxieties coursing through culture, the “traditional” art world—that of museums and biennials—has largely turned guarded and inward-looking, focused on historical reckoning. The crypto-art world, however, is almost the complete inversion: It is all Big Ideas and the sense of world-changing mission and the new and now. It is infectious and seductive—even if, as that Li quote suggests, the celebration of technical marvels seems to willfully overlook problems sitting right out in the open.

The stakes go well beyond the artistic sphere, though. Crypto’s promise for art is just an amuse-bouche for what NFTs can do, as far as the investors and tech disruptors are concerned—and they are definitely the ones who are setting the direction of travel. At the conference, I keep hearing that the digital-art craze has merely been the vehicle to get the public’s attention for this novel and inscrutable technology, which promises to be applied to every aspect of experience, in culture and in the economy.

By Day 3 of NFT.NYC, the final day, I get a sense of a near future coming into view, as I am exposed to a critical mass of people speaking from outside the visual-art side.

Representatives of the music industry seem very enthusiastic about NFTs as a way to open new revenue streams in the form of digital merch and as a vehicle for new forms of brand-building. At NFT.NYC, I hear NFTs pitched as a way to bring back the lost “middle class” of the music industry.

Apparently, if early-career bands give concertgoers an NFT, then they are not just fans anymore. Those fans will now see themselves as investors in the band, with a financial interest in promoting its success, as a way to pump the value of their digital token. It’s a bold image of a future where teenagers shape their music tastes around what they think sounds like the best investment.

For the many representatives of the video-game industry at the conference, a talking point is that teens spend so much of their lives playing games that they want to see some kind of return on investment for that time. A new wave of NFT-powered “play-to-earn” games promises to take activities that were previously considered fun and entertaining escapism and reimagine them—as jobs.

Axie Infinity, an NFT-powered monster-fighting game that is a bit like Pokémon, is one of the fastest-growing things in the NFT space. You pay money in the game for unique NFT monsters (“Axies”), and win an in-game cryptocurrency, Smooth Love Potions (SLP), that is convertible into real money (currently 1 SLP is worth about 5 cents).

The thing is, it is expensive to fight monsters in Axie Infinity, costing hundreds of dollars to buy monsters and requiring you to buy Ether, with all its associated fees. That’s where Axie Infinity Scholarships come in.

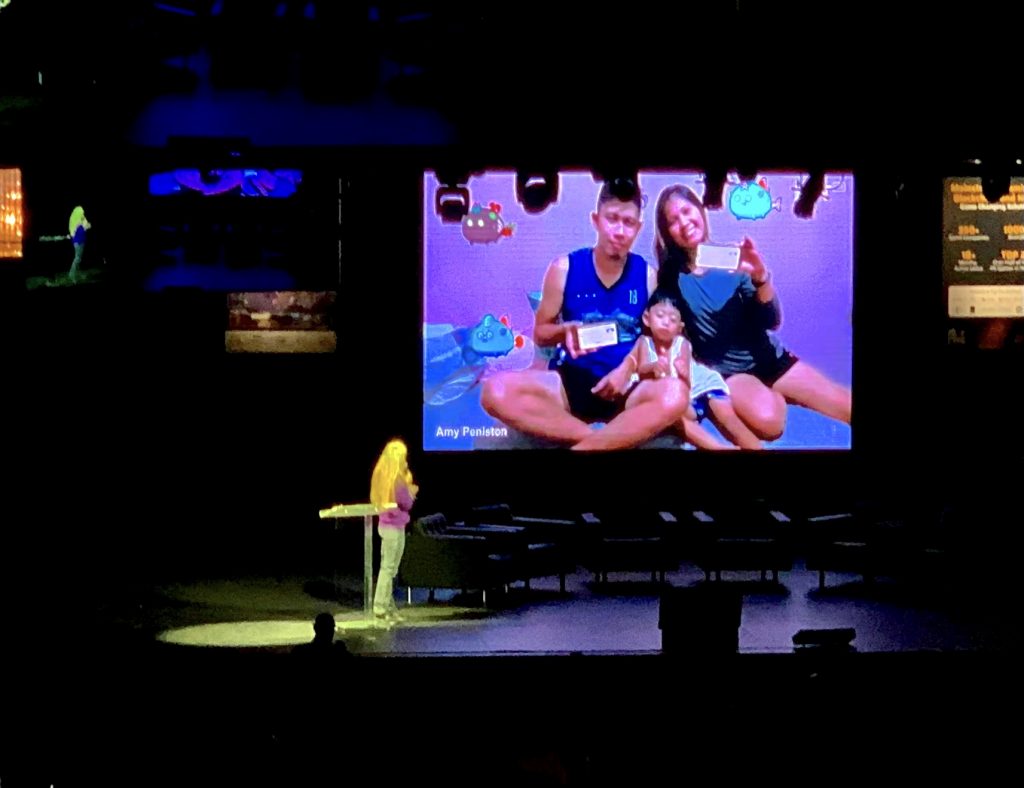

Amy Peniston gives an emotional speech on Day 3 about her work with Axie Tech, an organization formed in the orbit of the new Axie Infinity economy. She says that she was purposeless, working in the reinsurance industry, before she found the idea of Axie Infinity Scholarships.

Once, a “scholarship” denoted a grant to further one’s education. In Axie parlance, however, it is a program whereby a manager, like Peniston, selects a gamer to sponsor, giving them access to some of those pricey monsters to do battle in Axie Infinity in exchange for a cut of their earnings.

Amy Peniston shows a picture of her Axie Infinity Scholar. Photo: Ben Davis.

After receiving over 2,000 applications from would-be warriors, Peniston picked her first scholar. She throws up a slide. “Her name is Mary, she lives in the Philippines, she’s a young mother, and she really needed the extra source of income,” she explains. (A very large percentage of the game’s players are in the Philippines.) Peniston describes Mary’s tears of joy when she discovered she had been picked to play Axie Infinity.

Each of Peniston’s scholars earns about $300 a month. “I get so many messages about how life-changing it has been,” she says. Mary’s husband, who lost his job during Covid, also fights for her now. Through their game earnings, they have paid off some of their loans and are moving into a new house.

But Peniston knows her audience, so there is a further twist to this pitch:

Now as a manager, you might be thinking, what’s in it for me as an investor? What are my NFTs going to be getting me? … From my experience, teams pay for themselves in about three to four months. After that, it’s profit. After that you can then reinvest or do what you will with your profits. At Axie Tech, we’ve been seeing about a 300 to 400 percent APY [Annual Percentage Yield] for our managers that are on our platform. That might not be the highest thing in this world of NFT flipping, but when you think about the lives you are changing with this scholarship program, I really can’t think of a better way to spend my money.

In fact, if you are not into the philanthropic angle at all, she goes on, there is even a service where you may simply invest money and have your management delegated. Then you can just watch the earnings roll in as your scholars battle it out online.

I read later in Wired about corporations buying and breeding hundreds of Axies to farm them out, taking advantage of the vast pool of people looking for work online in a connected global marketplace. Meanwhile, a study of earnings trends within the game suggested that the realities of the grind needed to make a real living in Axie Infinity, given the cut taken by managers, was already setting in: “Scholars are very close to realizing that playing Axie isn’t so different from a minimum-wage job after all.”

The idea of a Ready Player One reality seems incredibly close—just a few clicks away.

It’s been a month since NFT Week in NYC, an age in internet time. If there’s one thing I learned, it’s that things are developing fast. So let’s skip to the end.

Thursday night, November 4, marked the arrival at Terminal 5 of Dreamverse, a giant music and art festival whose slogan is “Where NFTs Make Landfall.” Dreamverse was meant to be the big event of NFT Week in New York, but was somewhat upstaged by the Bored Ape Yacht Club, which pulled off a massive banger the night before, featuring the Strokes, Lil Baby, Beck, Chris Rock, Aziz Ansari, and Questlove.

Still, if “Beeple, Beeple, Beeple” is the mantra of the week at NFT.NYC, then this was the place to be. Sponsored by Metapurse, the crypto fund behind the $69 million Beeple buy, it promised not just a program of popular DJs, fronted by EDM star Alesso, who would debut his own line of NFTs at the event; not just a program of digital art, distributed around the venue; not just a new work by Carsten Höller, the “relational aesthetics” pioneer known to the traditional art world for putting playground-style slides in the Tate Turbine Hall—no, it promised the debut of a 3-D immersive version of Beeple’s Everydays–The First 5,000 Days, billed as a proof of concept for how the publicity around big prices for crypto-art might be translated into IRL gold.

I arrive early to a teeming line. There are people handing out Guy Fawkes masks (a promo for NFTimes.me). On one side of me is a nondescript fellow from a publisher of NFT-based games. On the other is Bosco, who has a beard that converges into a braid, like a pirate. He hasn’t even heard of Beeple, and seems puzzled when I tell him this is an art event. “I’m here to rave,” he says. “I thought, with the tickets being so expensive, I might have room to really dance.” (Tickets start at $175.)

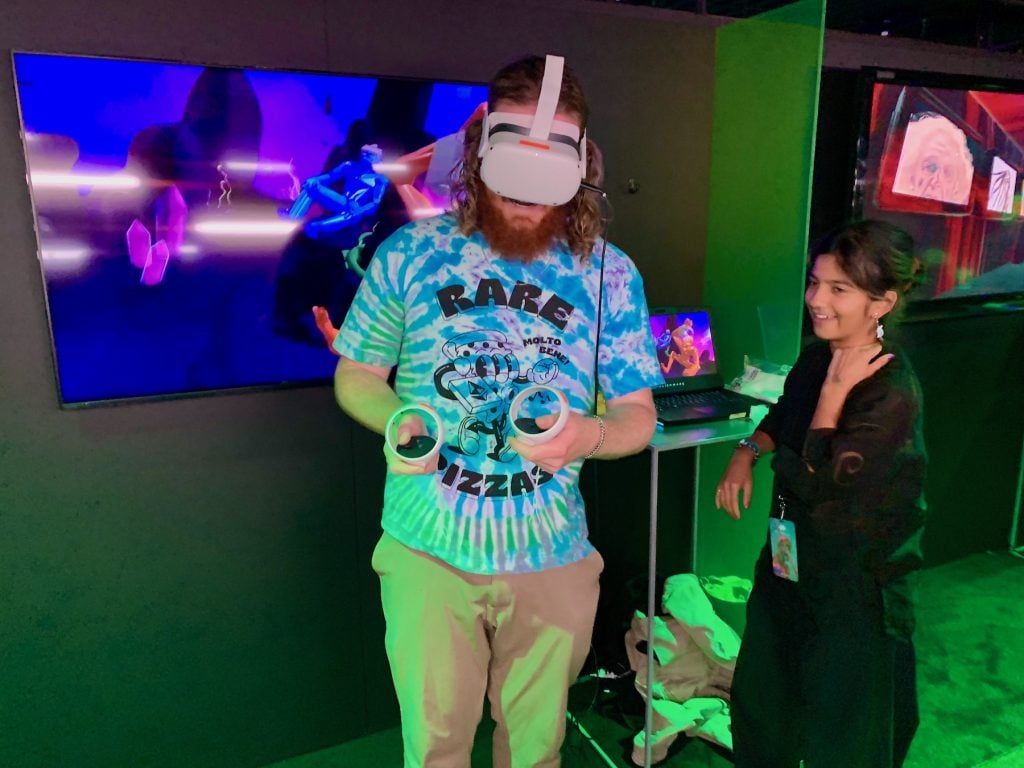

Guests interact with the art at Dreamverse. Photo: Ben Davis.

As people pack the venue, our emcee for the night—the well-known alt-auctioneer CK Swett—takes the stage to welcome everyone to Dreamverse. “We’re here to celebrate a new era, one that is not dictated by the colonizers, but that empowers all to have a voice,” Swett proclaims. He is wearing a purple suit, bow tie, and fur coat.

I realize now that arriving on time, at 8 p.m., has been a mistake. The part I am interested in, the Höller and the unveiling of the Beeple, will not happen until past 11 p.m.

Still, there’s enough to do. On the levels of the club overlooking the main dance floor, banks of screens flicker with a curated selection of work by prominent NFT artists. There are VR stations where you can sample still more digital artworks in simulated space (I have a lot of trouble remembering VR art. As soon as I leave it, the images slip away like dreams—does this happen to anyone else?)

A VR station at Dreamverse. Photo: Ben Davis.

There are long lines for AR photo booths, which send you a short clip of yourself that makes it look as if you are interacting with a NFT-inspired cartoon in real life—in my case a Meebit, a boxy little creature by the same people who made the CryptoPunks.

There’s a refreshingly non-digital attraction where an amiable artist who goes by the name Napkin Killa gives you a caricature of yourself that he draws on a napkin. Killing time in the half-hour line to get my napkin, I meet Beth, who works in real estate and doesn’t know what an NFT is, and is here because a friend of a friend knows the organizers. She Googled Beeple a few hours ago: “He’s out there.”

Napkin Killa drawing portraits at Dreamverse. Photo: Ben Davis.

It’s all amusing enough, even if it has the slightly mix-and-match, rent-a-party quality that I associate with rich people or corporations trying to seem fun.

I drink two $13 Sea Breezes.

The dancing is slowly gaining momentum as 11 p.m. approaches, though it’s not hard to grab a place front and center for the start of the art program. I run into Bosco again, bobbing his head and looking annoyed. I ask him if this is what he came for. He rolls his eyes and looks around at the crowd, where there is still more mingling going on than raving: “No.”

And then the music stops and the promised program begins.

CK Swett reemerges and seeks to impress the audience by quoting Goethe, intoning that “architecture is frozen music” as a way of introducing three men in vests and blazers. They are the digital architects known as Holly13, and they are here to show a clip of the MetaSouk, the new virtual museum they have created for Metapurse to display its NFT art purchases in the simulated 3-D space of the metaverse.

“En-ef-tee?” a woman standing behind me asks her companion. “What is that?”

“It’s art,” he replies, confidently. “Art on your phone.”

Spooky, portentous electronic music plays as Holly13’s film gets going and we are swept through the halls of a lavish virtual museum. The landscape has a laminated, hyperreal air. There is a vast field of mushrooms, an impossibly huge gallery, and then a space that appears to be an immense atrium that you can soar up inside, its sides wallpapered with the densely tiled images from Beeple’s Everydays.

I have to admit that MetaSouk looks to be an improvement on the B.20 Museum, the previous metaverse exhibition space Metapurse commissioned in the online universe of Decentraland to show its Beeple works, which I previously reviewed. Still, the audience around me seems confused.

“What the hell is this?” someone near me says.

“Where’s Alesso?” someone calls out.

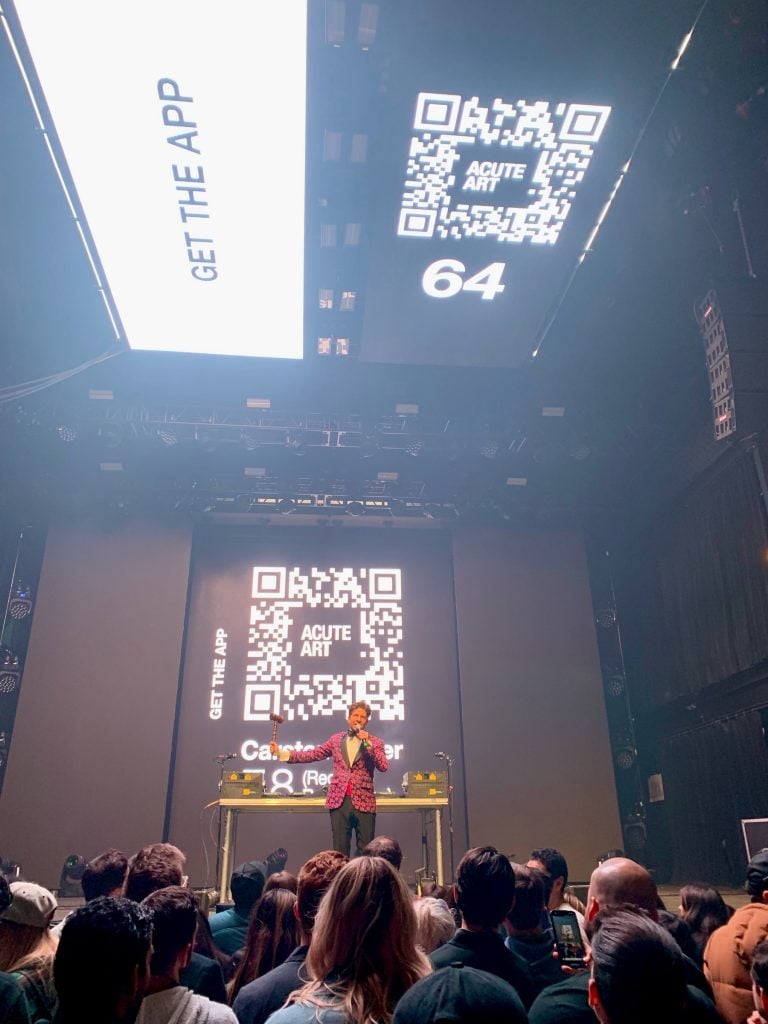

The lead-up to Carsten Höller’s “reduced reality” experience at Dreamverse. Photo: Ben Davis.

To their disappointment, Alesso is not next. Swett now has the thankless job of getting people excited about the “reduced reality” experience, courtesy of Carsten Höller and AR platform Acute Art. This will require that everyone download an app on their phone, then click to the appropriate screen, where they will hit a button simultaneously. This will activate a light and sound combination that, when heard together, will supposedly induce a mildly psychedelic experience.

In a development that could only have been anticipated by anyone who has ever been to any live event at all in their life, this does not go well.

A giant QR code on the ceiling encourages people to download the app, while a countdown clock is meant to coordinate the button-pushing. But people are either not downloading it, or downloading it and then immediately pressing the button, causing uncoordinated bursts of light all around as we wait for the promised big moment.

People are booing and calling out for Alesso. “You will get Alesso, but first you have to get the app,” Swett tells the crowd.

For some very embarrassing minutes, Swett is reduced to pretending to do a striptease, seemingly in an attempt to center the room’s wayward attention. The countdown clock continues, everyone either fiddling with phones or ignoring the stage completely and talking.

At last, the experience is set off. There is a roar of light that yields to darkness and a pulse of low-frequency sound, phones flickering along here and there. If there is any druglike effect, it is more CBD than LSD.

The crowd thrills to Carsten Höller’s “reduced reality” at Dreamverse. Photo by Ben Davis.

“What did you get out of that?” I ask Beth, the woman from the Napkin Killa line.

“Literally nothing,” she replies.

Anticipation for Alesso is peaking—but now we are on to the unveiling of the IRL version of Beeple’s Everydays.

Personally, this is what I am here for. I am intrigued to see how they convert the image to its promised “immersive” form. I imagine a synthesis of the two big trends of the year, NFTs and Immersive Van Gogh. And I want to know how they deal with the more stomach-turning Beeple pictures, the early-career images like “It’s Fun to Draw Black People”—about which Beeple himself has expressed regret, even as they remain forever fixed in the $69 million opus.

But it turns out that Immersive Beeple is really just what used to be called “a film.” (I gather more ambitious ideas were nixed.)

A film of Beeple’s Everydays—The First 5,000 Days is shown at Dreamverse. Photo: Ben Davis.

Once more, portentous, droning electronic music plays. People throw up their phones to record. On a large screen—slightly obscured, for me, by the DJ decks that remain onstage awaiting Alesso—we see the now-familiar indecipherable digital mosaic of the Everydays, containing every image that Beeple posted, daily, for 5,000 days. We then zoom in to focus on specific images up close, and for a few minutes, we move into and out of different parts of it, seemingly randomly skimming up and down and all around the collage.

Thus, we fix for a second on a picture of a crowd of monks worshiping a floating pyramid. Then on a pack of Baby Yodas slicked with blood devouring the carcass of a dead Jabba the Hutt. Then on an immense Buzz Lightyear, attended to by two men sucking at hoses attached to his waxen, lactating breasts.

The film ends to big cheers from the crowd. In front of me, a woman in a jean jacket has the words “ALESSO IS DADDY” on her iPhone and has put it to her forehead. She swivels to the crowd all around her, pointing at the screen and trying to get them to chant. “Alesso! Alesso! Alesso!”

But not yet.

Twobadour, Beeple, and MetaKovan at Dreamverse. Photo: Ben Davis.

Now MetaKovan and Twobadour, the financiers behind Metapurse and this whole spectacle, emerge from stage left, flanking Beeple, who seems as affably sarcastic as ever (“Nobody told me we were saying stuff”). There are cheers, but from around me there are also some more complaints and chatter so that it is hard to hear what they are saying.

I hear them say something about NFTs.

“Oh my God, do they think we really care?” the woman behind me blurts out in fury, literally stomping.

MetaKovan and company retreat. And Alesso, at last, emerges. The Terminal 5 stage lights up and the beats, the lasers, and the smoke machines go to work. The dance floor quickly becomes an impassable mass.

Alesso takes the stage at Dreamverse at last. Photo: Ben Davis.

NFTs have made spectacular landfall, but the organizers themselves don’t yet seem to totally know what kind of energies will be released by the collision, or how exactly to harness it, or where it all might go…

Thinking these things, I made my exit from Terminal 5. And that is how NFT Week in New York ended.