If Frieze New York were more conveniently located—with all the Ubers in New York, you still couldn’t get a car out of Randall’s Island during last week’s fair—with better, broader art in a (way) more opulent and comfortable setting, it would have been called TEFAF. Any gallery that did a booth in both fairs this year won’t next; of that, I can assure you. When I asked one TEFAF dealer straddling the two fairs who she had sent to tend the gallery’s booth at Frieze (the misnomer of all time), she replied, “We put the new guy in the oven.” Like a hazing ritual.

Maastricht’s TEFAF famously carries (drags) on for 10 days, and the New York version lasts for a nearly a week. This strategy affords opportunities for more than a passing glance at the work on view, and promotes deeper, more meaningful relations with the art and dealers (primarily for locals). The vetting process is stringent, if not beyond that. One dealer was sternly criticized for the restoration of a Calder, even though the work had been carried out by the estate—what better provenance is there? Can you imagine vetting at a fair like Frieze for… good art?

(Re)united in art: Britpop’s Pulp frontman Jarvis Cocker, who previously collaborated with Currin (pictured right) on a video for a song entitled “Help the Aged.” Now we all are, and need it. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Pulp’s 1998 album This Is Hardcore featured a John Currin (b. 1962) painting on one of its covers (the other was by Peter Saville) and the video for the song “Help the Aged” was littered with them. We’ve all come a long way since then (we’re all old now), but I spied the artist and the artist Rachel Feinstein (b. 1971), his wife and sometime model, together with Pulp’s lead singer Jarvis Cocker (b. 1963) at the Upper East Side’s Sette Mezzo restaurant—a dump with great food and better people—just prior to the onset of TEFAF. I met Currin not long after his Yale MFA in 1986. For the record: Kenny Schachter (b. 1961).

John Currin and Rachel Feinstein. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The fair is meant to elicit the feeling of times past, and Gagosian got right into the spirt with painted ersatz velvet walls. (Don’t get me wrong, there are worse ways to fritter away an afternoon than harkening back to another era surrounded by great art.) On view at the gallery were a slate of new Brice Marden and Currin paintings. I missed Marden, but caught Currin post-lunch and eavesdropped the following comment by the esteemed artist as he was entering the booth: “There should be a sticker affixed to the wall beneath my paintings: ‘PRICED TO SELL! 30% OFF!'” There was no need for a fire sale, however (that was the purview of Frieze). Before Currin had finished his espresso at lunch, a portrait of his wife had sold near the $3.5 million asking price. Some of us have come a long way indeed.

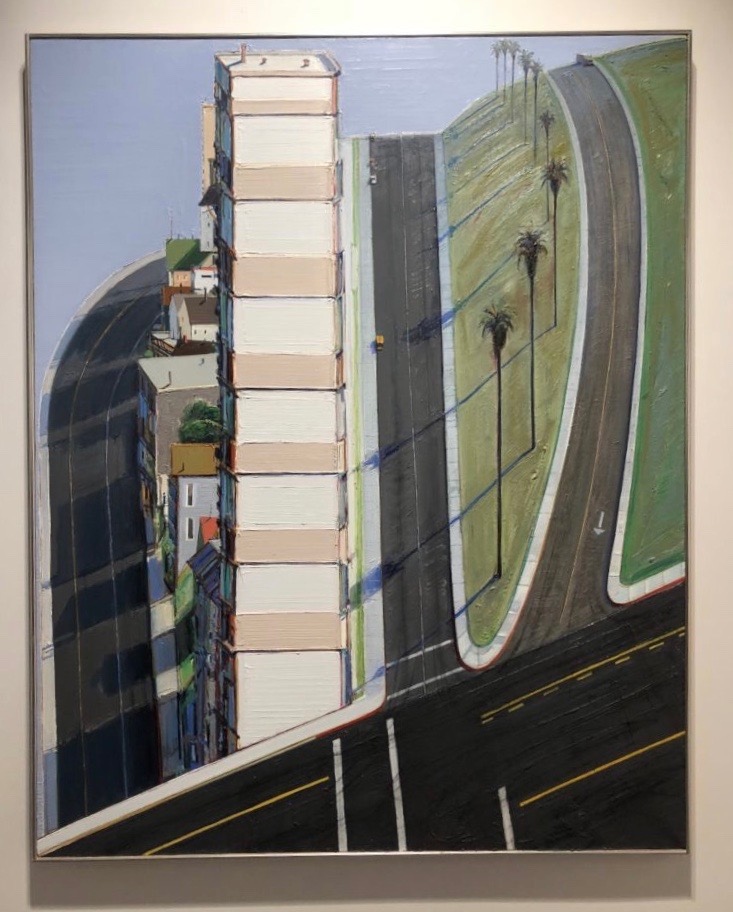

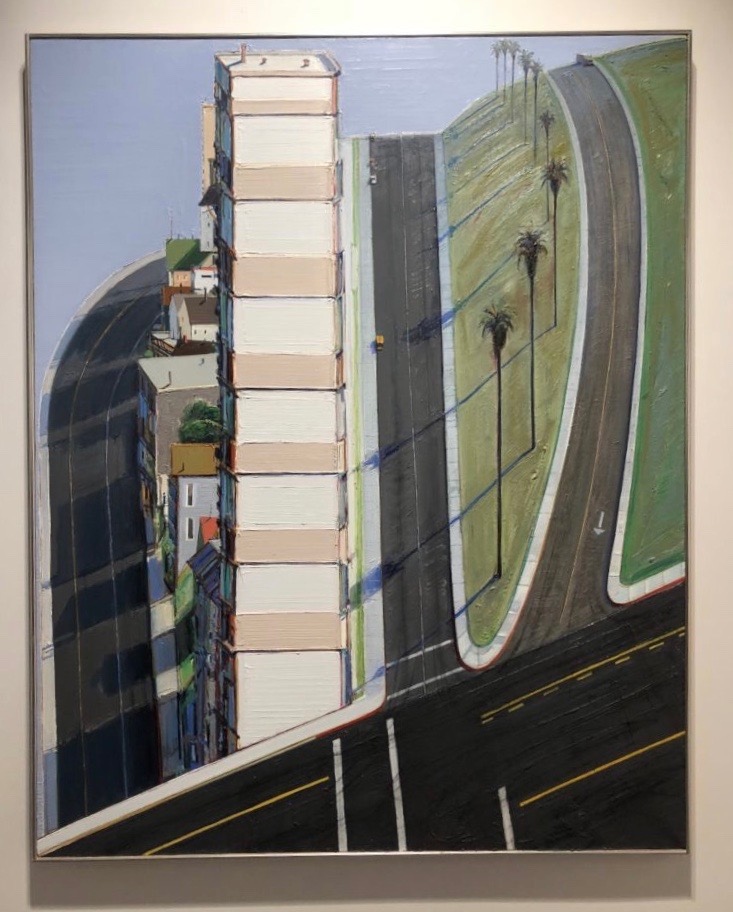

It was raining Wayne Thiebauds last week (if you factor in Acquavella’s Frieze booth), who at the ripe age of 97 could still easily embarrass me in tennis. Thiebaud is the subject of an upcoming drawing show at New York’s Morgan Library, “Wayne Thiebaud, Draftsman” (May 18 – September 23). The priciest was a stark streetscape at Eykyn Maclean, Palm Ridge from 1977-78, available for an equally severe $7 million. (It was the talk of the Thiebaudistas.) There were also some tasty cakes from 1962 for $2.9 million at Edward Nahem and, the most accessible of the lot, a cupcake collection on paper for $775,000 at San Francisco’s John Berggruen Gallery.

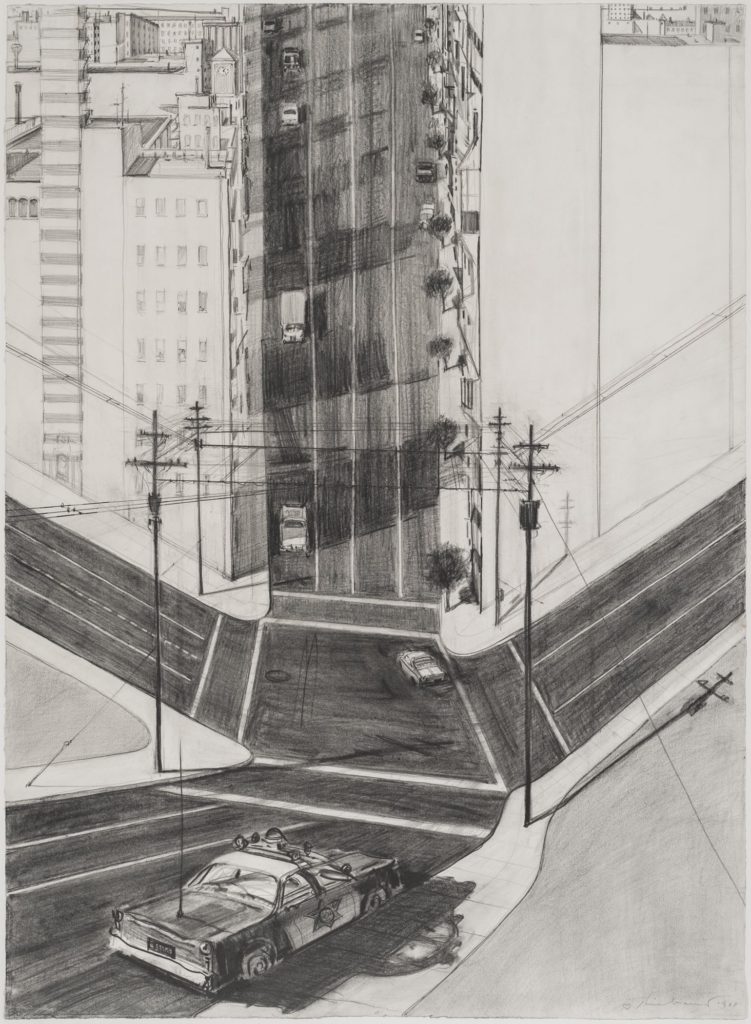

It was raining Thiebauds, including this beauty at Eykyn Maclean for an equally beauteous price of $7 million. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

Berggruen, son of Heinz and half-brother of Nicholas, hung his first shingle in 1970. He is cast in the mold of the old school; when I asked him of a tiny $550,000 Mark Grotjahn drawing on hand, he said, “It’s awful and I only recently bought it at auction” (which he did in June 2017 in Sotheby’s sale of little works, for $406,218). He also called a Shara Hughes (b. 1981) “way overpriced” at $90,000 (her auction record is $68,750). He’s charming and forthright, and the combo is awfully cute. He reminds me of London’s Leslie Waddington, recently deceased, another great, honest-to-a-fault dealer. Not many remain.

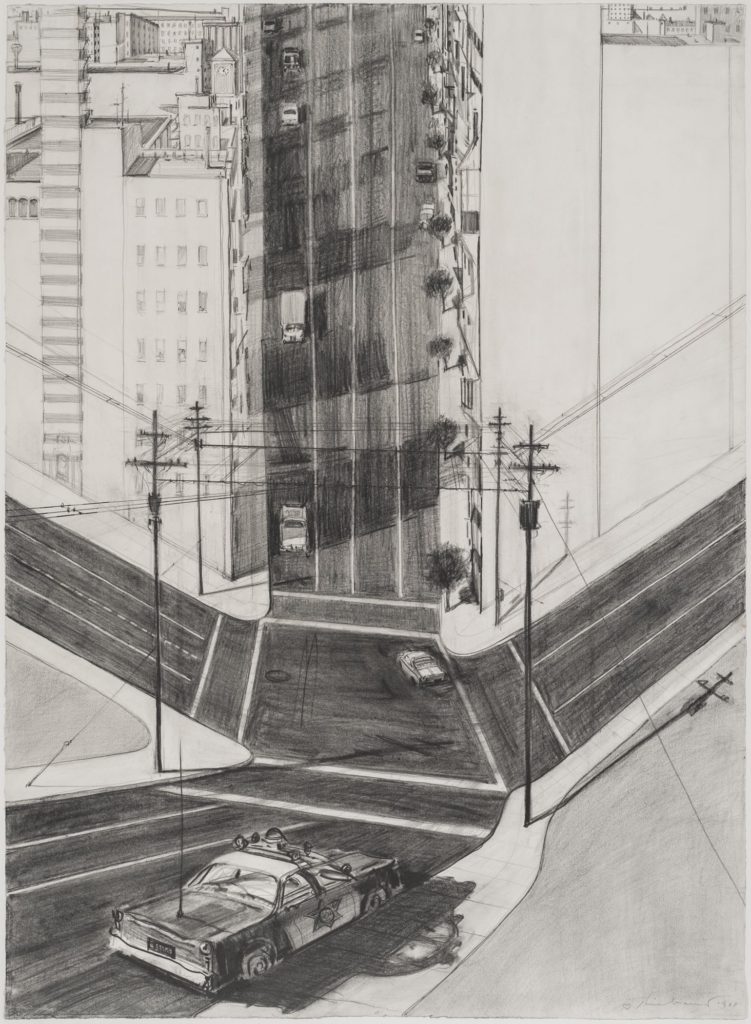

I grabbed this Thiebaud from Alan Stone Projects at the gallery—don’t think they did any fairs this cycle. The artist is the subject of a drawing show at the Morgan Library next week. People don’t appreciate drawings as much as they should. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I grabbed another Thiebaud in a visit to the gallery of the formerly primary-market Alan Stone Projects (they didn’t do any fairs this cycle). People don’t appreciate drawings as much as they should. I bought—well, I’m still paying off the last purchase—a 1970s pencil landscape of an upturned San Francisco street scene as if seen from the perspective of… a scary LSD trip, complete with a police vehicle on the scene. I like Thiebaud’s unorthodox, less confectionary works (in any medium) as much as a fat slice of cake. And let it be said: I wouldn’t have visited the gallery had it not been for forging a relationship at EXPO Chicago.

Though I am a longtime fan of Martin Kippenberger, and bought a sculpture in the 1990s (which I sold when it started to dissipate in real time), I could not to this day understand what separates a $500,000 painting from a $1 million one. Can’t know it all. There were a selection at TEFAF ranging from a spectacular series of self-portraits, the Raft of the Medusa ($275,000 for edition #24 at Skarstedt), depicting the artist on his premature deathbed from cancer, a matter of lifestyle catching up with life. (Artists—and dealers, take note.)

Skarstedt also had a painting for $1 million, the same scale as a work for half the price at Friedrich Petzel gallery, while another was tagged at €600,000 at Gisela Capitain, who I’ve been acquainted with since forever. When I queried the price of her Kippenberger, pointing at the work to make myself that much clearer, she incredulously spun around on her heels and demanded, “For which work?” There was one piece on the wall and this was the first day of the fair—I shudder to imagine what her wherewithal was like after five full days at the fair.

The super-suited Wildenstein gang, who would give Jeffrey Deitch and Andrew Fabricant of Richard Gray (see below) a run for their money in the best-dressed category, were stepping outside of Maastricht proper for the first time, which they had only done on two prior occasions. (This was their third-ever fair!) They presented an amazing array of Pierre Bonnard canvases (and some choice drawing) including a nine-foot-wide horizontal landscape. When I pestered them for the price—$18 million—they responded, “Not for print, right?” Oh sure. Guess they don’t read me (or haven’t ’til now).

Wildenstein hits the fair circuit running with a booth devoted to Bonnard, including this smoking self-portrait for $400,000 (shh, not for publication). Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The ginormous landscape, Paysage du Cannet from 1928, last sold at auction for $5 million in 2005. Better bargains could be had for drawings—god, I love works on paper—ranging from $50,000 for a simple rendering of a bather in a tub to $400,000 for a pipe-smoking self-portrait. In any event, it was a breathtaking cluster of art, but they only offered me all of a five-percent discount on a drawing. Okay, I was only in my standard-issue polyester Adidas, but they didn’t have to treat me like a hooligan. They really need to get with the times.

Another frustrated Frieze exhibitor, Richard Gray Gallery, said there is no question of them crossing Hell Gate to Randall’s Island again. (A partner at the gallery called it: “a shit show, in conditions not unlike the Bataan Death March, that resulted in nothing more than an appalling, limp d*ck apology from management.”) Their Sam Francis booth was hung in such a minimal, museum-like installation that a friend mistook it for a noncommercial outing. Luckily for the gallery, not everyone did, and one of the major canvases went for “north of $20 million.”

People often complain that the art world is full of shady acts of legerdemain—proving this party true was David Blaine, seen at a Simon Lee’s booth performing a card trick for his pal Helly Nahmad (aka Shelly Habib in Molly’s Game). I overheard the dealer remark, “Can you conjure me some more business?” Another overheard gem, at Lévy Gorvy this time (it helps to have good hearing in my profession): “Why is there a such a wide disparity between the price of your Warhol Brillo Box”—sold at $900,000—”and that on the contiguous stand” of Peter Freeman gallery, on view for $2.3 million? The answer was pitched perfectly: “Ours is from Pasadena”—the Pasadena Art Museum—”and theirs is from Mugrabis.

Pick a box, any box—actually, that could be very costly, as one is from the Mugrabis. Photos courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

By the time I finished viewing TEFAF on the frenetic short trip (I will be back in a matter of days), I could have benefited from the care of a nurse. Richard Prince’s silkscreened and painted version, one of many from the series, was on view at Korea’s Gana Art with an asking price of $8 million. I am a big fan of the gallery, established in Seoul in 1983, which showcases a wide array of Asian and international artists. The dealer asked me about my kids’ art (very sweet) and what I thought of the Prince price, but such on-the-spot pressure was too much and I fumbled for a response.

So many fairs, I need a nurse! Richard Prince’s version at Gana Art. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

I am lost without a surf through artnet’s Price Database: do not mistake this for shameless pandering; it’s the least I can do for a company that suffers through the crap I regularly put them through (or rather, their legal department). From hindsight, the 12 highest prices ever paid for Richard Prince were all from the same series of nurses, and though the record is $9,685,000 (from 2016), the last aesthetically similar work sold for $5,847,000 that same year. I would say the price was about right to gauge the pulse of demand… sorry couldn’t resist a stab at medical humor.

The End (‘Til Next Week’s Auctions…)

Maybe there should be a fair in every city, 24/7: a perpetuity tent. In the best of worlds, fairs are hors d’oeuvres for gallery attendance; and, if not, they serve to draw people to art that wouldn’t visit galleries under any circumstances. They also bring together a bunch of freaks that could all benefit from a little more face-to-face socialization. In Switzerland it’s illegal to own a single guinea pig; left to their own devices, they are prone to die from loneliness. Me too (imagine that).

I have been dwelling on health this cycle, I’m not certain why. I’ve yet to brush with mortality (knock on wood, sorry to inform you). But, I wonder if the relentless march of fairs and auctions, etc., spread far and wide, prematurely ages art-goers. I received a social media missive: “Saw you walking in pain so did not salute you at TEFAF earlier, be well.” Another read, “I have a quick suggestion for sore feet due to slow art fair/museum meandering, Samuel Hubbard shoes, specifically the ‘Hubbard Fast’ sneaker. I do trade shows throughout the year and they have essentially saved my feet. If you want we can send you a pair.” The Hubbard Fast? Christ, think how much more art I could see!