Opinion

Summer Shocker: Kenny Schachter Hits the Art-Gossip Goldmine… and Keeps It to Himself

Our columnist shows unusual discretion after seeing something he really shouldn't have during the London auctions.

Our columnist shows unusual discretion after seeing something he really shouldn't have during the London auctions.

Kenny Schachter

I have noticed a surge in the level of homelessness in London, which was confirmed by a recent article in the Guardian that revealed steadily increasing numbers over the past seven years, with an 18 percent rise in 2017 alone. This reflects a marked change since I moved to the UK in 2004 amid booming art and property markets and a generally more optimistic social, political, and economic climate altogether. There was even talk of London stealing the mantle from New York as the center of the art world. Those heady days are long gone; the only category of note where London has surpassed New York is in murders, while the lame-duck government is in tatters and the property market lies stillborn. And all before the onset of Brexit.

In spite of this, Sotheby’s and Phillips posted strong sales results with their London contemporary auctions last week, significantly gaining on last year’s performances—as did Christie’s tiny gesture of a sale, though that was no big feat considering its abandonment of a June evening auction altogether last year. (That dereliction still stings, since London is Christie’s own front yard—it launched here in December of 1766.)

This will be a cursory report, as I am beyond exhausted by the continually accelerating churn of the global art market, and I’m sure you are too. So I’ll keep it short and sweet(ish), beginning with the obvious: Christie’s has been steadily battering Sotheby’s in most sectors for ages now—witness Sotheby’s anemic Impressionist/Modern sale a few weeks ago in London, compared to the monstrous Rockefeller sale shepherded by Christie’s in New York this May with astounding results. When you average out the year in earnings, bowing out of London won’t affect that momentum either—Christie’s will still be on top.

If Christie’s is at the top of the heap, mid-sized galleries seem to be at the bottom if talk of a gallery crisis is to be believed. Could the most unlikely of saviors, Art Agency Partners, hold the key to saving these galleries from extinction? For a fee, said to be in the neighborhood of $250,000, the Sotheby’s subsidiary will offer up gallery advisory services. I could use some help myself. But is an auction house teaching gallery management to galleries, for a sum that would bankrupt the companies that need support the most, really a solution? Insert the hysterical emoji here. [?.]

Meanwhile, another tacitly accepted service that the houses all offer dealers (but rarely speak of) is the no-money-down policy where you buy now but only pay when you sell—well beyond the 90 days most auction addicts regularly insist upon. Credit you don’t need to apply for, with no interest? That’s my kind of loan.

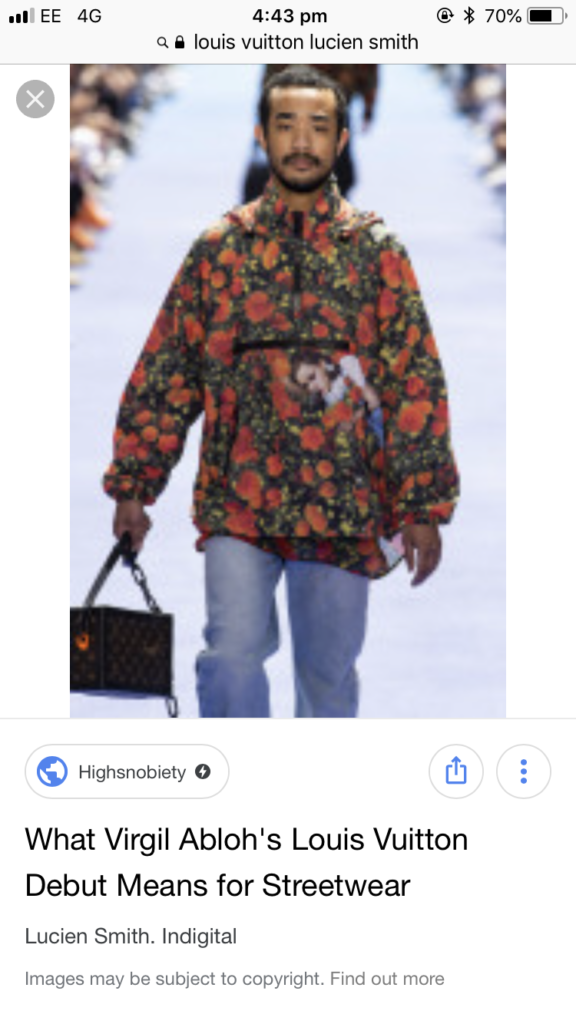

New Louis Vuitton creative director Virgil Abloh, the vaunted sweatshirt designer who collaborates with such artists as Takashi Murakami and Lucien Smith (who recently strutted the catwalk for Abloh), spoke of his interest in normcore fashion when describing his inaugural line for the LVMH juggernaut. For those not in the know, let me translate: the new trend is trying to look… normal. In a way, a drive toward normalcy aptly describes much of today’s alleged avant-garde (if such a thing could be said to exist); benign innocuousness seems to rule the day.

Lucien Smith walking in Virgil Abloh’s Louis Vuitton show. Watch it, he may be packing a loaded extinguisher in that bag. Image courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

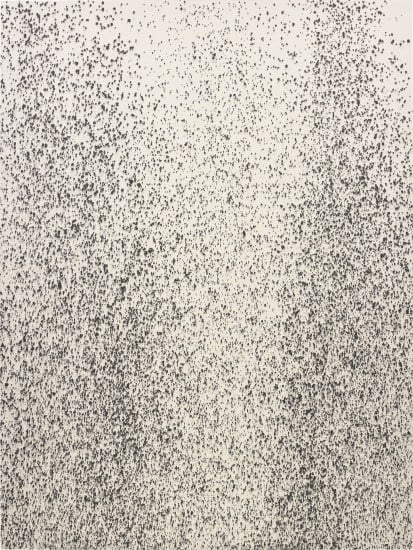

Speaking of Lucien Smith, look for a Zombie Formalism comeback in the years to come, though it will take some time: Smith’s rain painting just made $26,500 at the Phillips day sale, versus his high of $372,000 in 2014 for an indistinguishable work. To be clear, I don’t fault (most of) the artists who were caught up in the unprecedented market spike of 2011 to 2014; rather they were tools in the hands of ruthlessly manipulative investors.

Lucien Smith: it’s still raining, just not as hard as before. (I’m hanging onto mine.) Image courtesy of Phillips.

London’s Masterpiece fair, running concurrently with the auctions and recently taken over by the Basel mothership, bills itself as “The Unmissable Art Fair,” so I proved them wrong—I like a challenge. Make no mistake, as much as I adore them, and I do, even a fairmonger like moi gets saturated (and I am). I have a similar relationship with Bonhams—I know I should pay more heed, and I most definitely appreciate their efforts, but my attention span is a diminishing asset (akin to a flea at this stage).

Speaking of which, I’ve decided to focus my auction report on the results of a single artist, albeit one who many don’t even consider to be an artist: Banksy, but everyone knows is Robin Gunningham. Of the eight works on offer—two at Sotheby’s, five at Bonhams (street art being the house’s sweet spot), and another at Phillips—they together averaged 134 percent above their collective high estimates. Banksy even outdid Kaws, the other non-art art-market phenom.

Banksy… meet Schachtsy. Illustration courtesy of Kenny Schachter.

The standout, by a long shot, was Banksy’s Keep It Real, a canvas measuring 8 by 7¾ inches, executed in 2002, with an estimate of £50,000-70,000 ($66,120-92,568) that sold for a whopping £418,000 ($552,763) at Sotheby’s. If half a million for a postage stamp by a street artist is real, then so it goes. Per square inch, there aren’t many artists who have exceeded such heights, other than Rembrandt ($3.75 million for a 5-by-8-inch work), Picasso ($4 million for a 5-and-3/8-by-7-inch piece), and a Van Gogh letter to his brother Theo that made $5.5 million for the single sheet of paper measuring 5 1/4 by 8 1/8 inches. People should write letters more often. Lest I forget: the reigning maestro of the mini is Leonardo da Vinci, who boasts an $11.5 million result for a drawing on paper, sized 4 7/10 by 3 1/10 inches. Small is all (sometimes).

In an odd twist, the Phillips evening sale was actually staged at night rather than matinée-style, prior to a Christie’s or Sotheby’s evening sale—the usual when Christie’s is in the game. The evening event sold out, with every last lot finding a buyer, while Sotheby’s missed that distinction by one. When Phillips first entered the contemporary sector, the house helped give rise to the flipping craze by engineering a marketplace for recently made art by the recently born.

There are clear victims when primary-market art by emerging artists is instantly resold (and then resold again): such barefaced profiteering can contribute to destroying the reputation and/or reception of the artist and their subsequent work. The collateral damage from crass commercial opportunism to nascent careers is well reported. By nature, consigning a young artist to auction entails lying—no gallery will sell a single work to a buyer who evinces such malign intent.

There are other times—transactional flipping, if you will—where there are no causalities and the practice contributes to a healthy market. The only muscle left to gallerists is access to the art; the collectors, Prometheus-like, have stolen the power to bestow an imprimatur on new artists from critics and museums (tragically). But galleries are oftentimes capricious in wielding their gatekeeper power, so auction houses provide a meaningful way to circumvent fake waiting lists, where nothing counts more than who you are and who you know.

Besides, I firmly believe that once you sell something, it’s gone—a laissez-faire approach to life that boarders on libertinism (ask my kids). Though the ridicule is rampant, fair-and-square secondary-market selling of successful mid-career artists is victimless, and far from a crime.

When Joel Mesler of Rental Gallery in East Hampton announced that he was orchestrating a 30-year retrospective of my art on August 25th (yes, you heard that correctly), he was approached by someone who had managed to get their hands on something of mine ages ago and was ready to cash in. A Schachter resale, how funny is that? The fact that I have no market is beside the point—I could care less. Like many a Hallmark card has said, love is letting go.

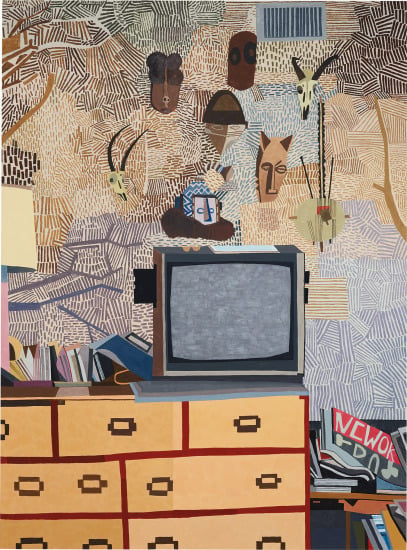

Jonas Wood, spinning gold faster than Rumpelstiltskin’s daughter. Image courtesy of Phillips.

A friend just bought a Jonas Wood in a Sotheby’s private treaty sale for $650,000 and didn’t like the way they were treating him with regard to another lot, so he turned around and secured a guarantee on the painting from Phillips for nearly twice the sum, ultimately pocketing about $1.5 million in a matter of weeks. The Woods sold for £1.57 million ($2.1 million) on an estimate of £700,000-900,000 ($918,000 – $1.1 million). So what? On the other hand, I bought a secondary-market painting made a few years ago by an in-demand artist that did well for the artist when I put it up at Sotheby’s last week, but less so for me—I lost on the deal. Equally, so what?

Exiting the Phillips evening sale, one of the house’s best auctions ever, I momentarily stood by the door to watch one of the last works hammer prior to my departure. Standing next to me was an employee who was carelessly using her clipboard as a shelf for her phone while she sent emails, and when I carelessly glanced over I was stunned to see it in plain view: the runner list for the evening’s proceedings. It beggared belief. For the uninitiated, this is the full Monty: a tallying of every consignor, reserve, and all the guarantors by name (and number). Wow, thanks! Imagine a Sotheby’s schmuck holding a runner list out in the open? You can’t, because it would never happen: they are forbidden from even printing such a document. Not even Bonhams would do that.

I can all but hear the edict ringing from Phillips when they read this: “Check the security cameras!” But don’t worry, I’m not telling, other than to say there were a few local London galleries, a Middle Easterner with a “museum,” an English film producer, someone who sold a lot of lots at Sotheby’s last week, and then Phillips themselves. I won’t reveal more—I’m not Julian Assange (even if I did snap an iPhone picture). As Paula Cooper put it while lamenting the Joan Mitchell estate defection to Zwirner a few days ago: “This art world has become so uncivilized.” I won’t be seen as an asshole by lowering the bar any further than some would say I already have. Enjoy the summer.