Auctions

Rockefeller Decoded: Christie’s Marathon of Sales Generated $832 Million—and Some Big Surprises, Too

A striking number of works on offer sold for more than five times their high estimates.

A striking number of works on offer sold for more than five times their high estimates.

Eileen Kinsella

What’s in a name? If that name is Rockefeller, the answer is more than $800 million.

After 10 days of online sales and three days of auctions—including two consecutive evening sales—the Rockefeller family’s wide-ranging collection of more than 1,000 objects sold for a grand total of $832.57 million. The result far surpassed the collective estimate of $600 million, though it was shy of the $1 billion figure bandied about in the press beforehand.

The fact that all the works sold is not entirely a surprise—the entire estate came with a guarantee, effectively securing buyers for the objects before the series began. But, thanks in part to a six-month, worldwide marketing campaign, a number of works soared far above expectations.

To be precise, 81.4 percent of the lots sold for above their high estimates, according to analysis of the major Rockefeller sales by the artnet Price Database. Notably, 19 percent—or almost one-fifth—of those sold for more than five times their high estimates.

A Pair of George III Walnut & Ash Armchairs, late 18th/early 19th century. Image courtesy of Christie’s.

While auction-goers may be used to seeing paintings by young contemporary artists sell for many multiples of their pre-sale estimates, it is rarer for decorative porcelain and collectibles to take such a trajectory. The vast majority of the objects that sold for more than five times their high estimate were categorized as decorative art objects, as opposed to fine art, according to the artnet Price Database. Most of these mega-performers originally had modest estimates under $10,000.

One highly prized example was Napoleon’s Sevres porcelain set, which the French Emperor took with him in exile on the island of Elba. It was estimated at $150,000 to $250,000—but ended up selling for $1.8 million with premium, seven times the high estimate.

Another seemingly unfashionable success: late 18th-century English furniture. A pair of George III walnut and ash armchairs that had been in the Rockefeller family since 1988 sold for $243,750—a staggering 41 times the high estimate of $6,000. Meanwhile, a pair of yew and elm Windsor armchairs sold for $212,500 on an estimate of $10,000 to $15,000.

Still, the highest prices went for blue-chip paintings, particularly by European artists. Each of the evening sales set seven new artist records at auction, including for top names such as Claude Monet, Henri Matisse, and Diego Rivera. The first evening sale pulled in a staggering $646.1 million, the highest total ever achieved in a single-owner auction. (It beat out the previous high of $484 million garnered in Paris in 2009 for the collection of fashion icon Yves Saint Laurent and his partner Pierre Bergé.)

The second evening sale generated a less eye-watering total of $106 million, but still set a record for the biggest American art sale ever. “Established and new collectors gravitated to the auction and it enabled us to achieve this monumental result,” Will Haydock, Christie’s head of American art, said of the sale.

The final $832 million total will be distributed among a number of charities, including New York’s Museum of Modern Art, the Council on Foreign Relations, and the American Farmland Trust.

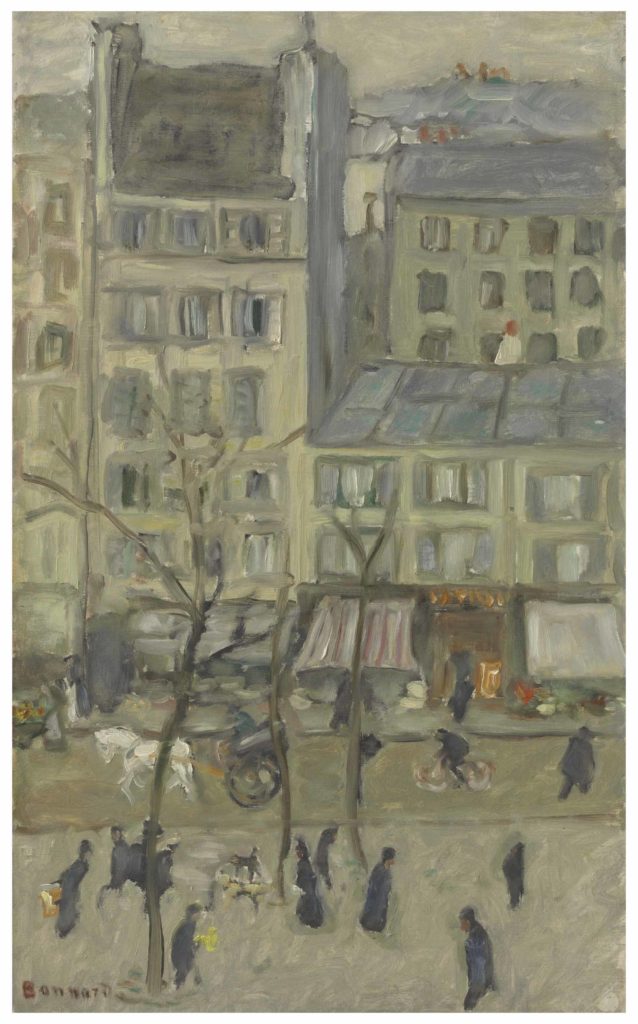

Pierre Bonnard’s Boulevard des Batignolles (ca. 1901). Courtesy of Christie’s.

There was the odd weak spot, with some paintings falling well short of even their low estimates. It’s difficult to discern exactly how profitable the overall sale was for Christie’s since reserves—the undisclosed minimum at which a work can sell—are kept secret. The guarantee given to the Rockefeller family was believed to be somewhere near the low estimate.

As some have pointed out, some works sold for far less than what Rockefeller himself paid for them. Marion Maneker of Art Market Monitor noted a small Georges Seurat painting sold for $732,500, around 50 percent of its $1.36 million purchase price in 2006.

Bloomberg‘s James Tarmy noted an even steeper decline: Pierre Bonnard’s Boulevard des Batignolles (1901), a gray-toned Paris street scene, which sold for just $250,000 on an estimate of $800,000 to $1.2 million. Rockefeller acquired it in 2006 for $856,000.

“Whoever bought it, in other words, paid less than a third of what Rockefeller had paid—more than a decade later,” Tarmy wrote.

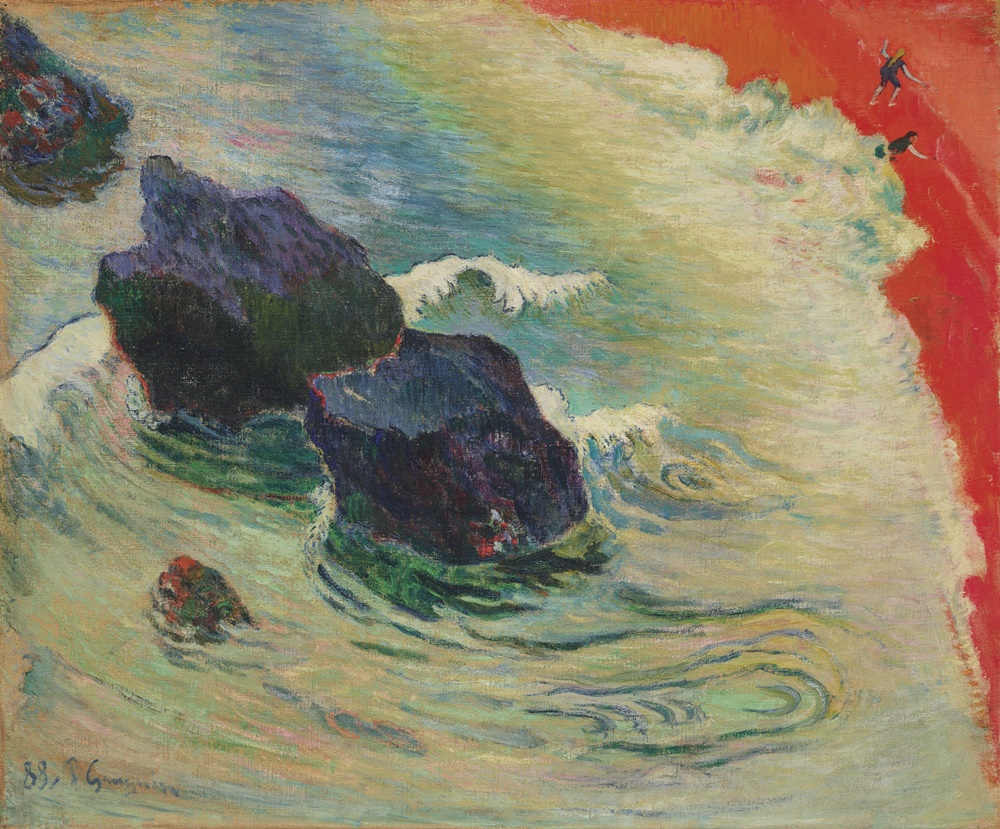

Paul Gaugin’s La Vague (1888). Image courtesy of Christie’s.

For some experts, the biggest takeaway from the sale was not the premium placed on the Rockefeller name, but the shifting tastes the sales illustrated across a number of categories.

Buyers seemed to prefer works with “wall power” over particular series or bodies of work that have already been deemed important by both the market and museums. “The most marked aspect to me was the shift in values within the same collecting field,” said David Norman, a private dealer and former longtime co-head of Impressionist and Modern art at Sotheby’s.

Referring to the $84.7 million Monet waterlily painting and the $80.8 million Henri Matisse Odalisque sold last Tuesday, he added: “I can tell you that during the first half of my career,” from the mid-’80s to 2000, “a luxuriant nude by Matisse would have never sold for less than a large, late stamped Monet; it would have been multiples higher.”

Further, he says it would have been unimaginable to think of a folding screen painting by a little known Nabis artist, Armand Séguin, making more than a classic, grand-scale interior by the greatest Nabis painter, Pierre Bonnard.

Another surprise was delivered by a crowd favorite, an uncharacteristic but gripping seascape by Paul Gauguin. “While it was one of my favorite works in the sale, I would never have predicted back then that an 1888, pre-Tahitian Gauguin would edge out both a historic Gare Saint-Lazare by Monet and a rare pointillist work by Seurat,” Norman said. “Each one of these works were marvelous, but money was simply going more aggressively toward pictures with greater wall power than historical significance. And that’s OK, things change—but it’s interesting to take note of how they do.”