Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

Now that more people are vaccinated, I have been throwing dinner parties that revolve around discussing articles in The New Yorker. (It’s sort of like a book club, but with less commitment.) We kicked it off with the profile of Ari Emanuel, moved on to a surprisingly political conversation about Robinhood and, in our latest iteration, analyzed William Finnegan’s piece on horse racing. Now, I have heard that a colleague has started her own dinner series with the exact same premise, though I assume the articles under discussion are different. My partner and I have accepted that imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, but settle an argument for us: could I theoretically copyright the concept of these dinners and sue her?

No. And since this came from a burner email, I have to ask: are you Whit Stillman?

I love your concept, and it is unique to be sure—but one of the tenets of copyright is that the work be “fixed in a tangible medium of expression.” Your parties are likely many things, but they don’t occur in a tangible medium of expression the way words on a page or paintings on a canvas do. Concepts cannot be copyrighted, and that’s actually a good thing, because it stops people from coming up to artists like Damien Hirst and saying, “I had the exact same idea in 1995!” Best of luck with your rivalry all the same.

I heard about the Pepe the Frog NFT selling for $1 million and was shocked to learn that it’s the first one officially by Pepe’s creator. Are all those other Pepe NFTs counterfeit?

Oh, dear. It sounds like you don’t know very much about Pepe, and it’s a wild ride. So let’s start at the beginning, shall we?

Pepe the Frog was created by Matt Furie in 2005 for a stoner online comic strip called Boy’s Club. It had a whole cast of characters, but for whatever reason, Pepe really spoke to people on message boards, and his face became ubiquitous in memes without incident for a decade. Then, more or less arbitrarily, the alt-right adopted him as its mascot, and by September 2016, the Anti-Defamation League had officially named Pepe a symbol of hate.

All of this was detailed in a pretty good documentary that shares its name with Pepe’s catchphrase, Feels Good Man. In it, Furie appears as a kind and frustrated cartoonist who never could have guessed what would come of his simple frog drawing, the copyright to which is his.

The thing about copyright is that it assumes, as the material circumstances under which it operates, a society where people are doing business out in the open and with accountability. And even if you don’t know much about Pepe, you do probably know that the internet is not that kind of place. The culture of authorship in general is much weaker online (for more on this, see the Lizzo answer later in this column). I think most people would be surprised to learn that Pepe has a creator at all.

So, are all the other Pepe NFTs counterfeit? That presupposes that the purchasers care if their NFT was made by Pepe’s original artist, which most of them probably don’t. I think most people in the market for a Pepe consider him to be something of a fair-use folk icon.

This is obviously a different attitude than most art collectors have. For many of them, the artist’s name is the big draw. But I think we’re learning that, while there is overlap, art collectors and NFT purchasers are two very different groups of people. It’s exciting because the NFTs that are made by “real” artists can reach a new audience, but it’s also a little scary because these folks don’t always play by the rules of the art world. We’re all learning to adapt.

Lizzo on the red carpet at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards, at the Los Angeles Convention Center on March 14, 2021. (Jay L. Clendenin / Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

I work in A&R for the pop music industry so I’ve been following Lizzo’s copyright infringement case closely. I was hoping you could explain something to me: If neither Lizzo nor the songwriters suing her came up with the line “I just took a DNA test, turns out I’m 100 percent that bitch,” then how is there still a case over who should be credited on the song?

It’s a little ironic that after “Truth Hurts” has been played enough times to take it platinum six times over, we still don’t have a clear picture as to who, in fact, “that bitch” is.

If you’re just tuning in, this case has been going on since 2019 and involves a spat between Lizzo and songwriting brothers Justin and Jeremiah Raisen. During a writing session for a different Lizzo song, “Healthy,” the brothers Reisen found a viral tweet about a DNA test by the London-based Mina Lioness. The Raisens suggested using it in “Healthy,” but Lizzo, as her many fans know, decided instead to use it on “Truth Hurts,” on which the Raisens are not credited, but for which they now claim songwriting credit.

Lost in this is the fact that neither Lizzo nor the brothers actually wrote the line. It was Mina Lioness, who was finally added to the credits for the song in 2019, making her belatedly entitled to some of the royalties. But the Raisens are asking for even more than that: they want joint authorship credit. Quite the prize in music, authorship credit enables the writer to exercise the copyright fully, which means they can license the song without the consent of the other authors. (That’s why most professional songwriters, like the Raisens, tend to work out rights questions beforehand.)

Judges seem skeptical that the Raisens’s suggestion could constitute full co-authorship, but it should be noted that a single Kanye West song can have nine co-writers, some of whom might contribute only a line or two. (You’ll find more information about song co-authorship in this article by the California Western School of Law.)

The case is complicated: Mina Lioness may have typed out that famous sentence on her phone, but she wasn’t in the room with Lizzo when she was working on her debut EP. Moreover, the question of whether or not individual tweets are protected by copyright is still an open one. In the meantime, it would seem that aspiring songwriters, like the rest of us, would do well to stay off Twitter.

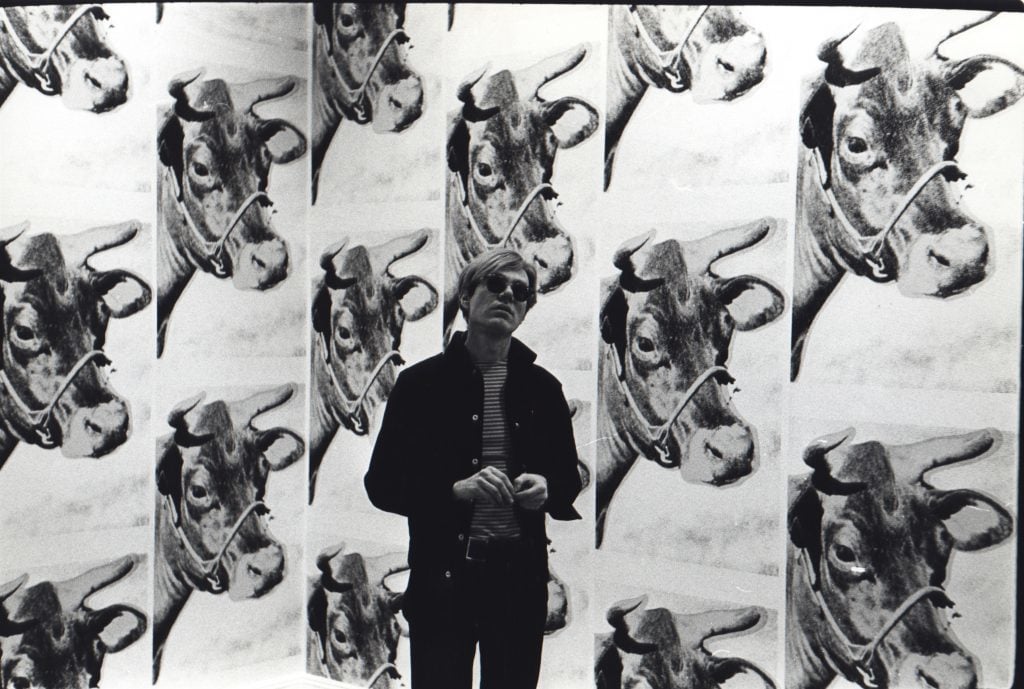

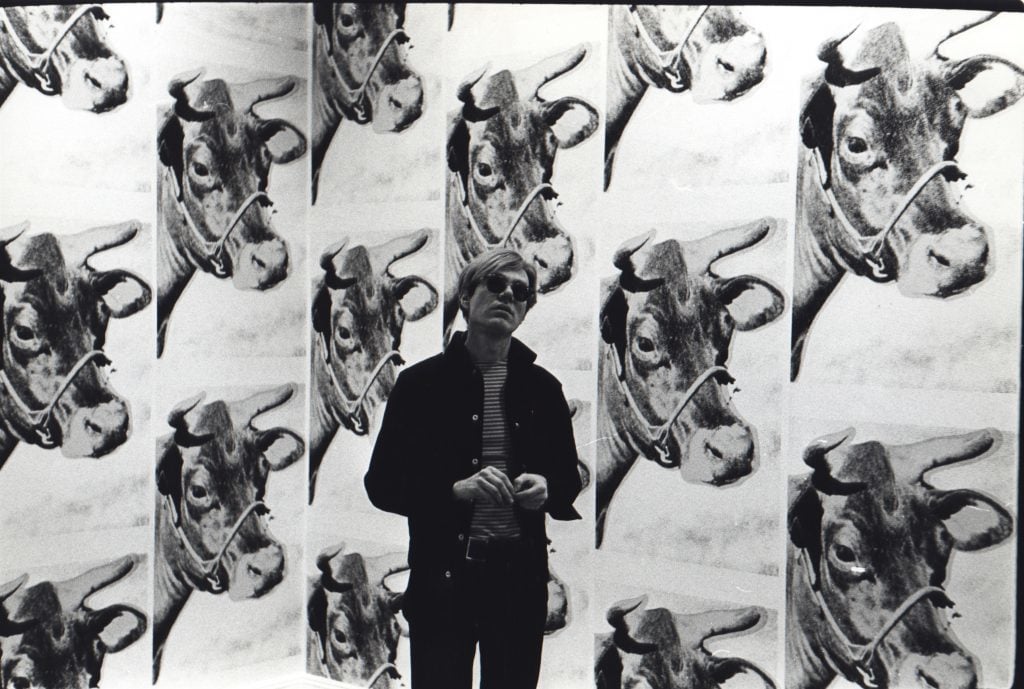

Andy Warhol with his Cow wallpaper at Leo Castelli (1966). Photo by Fred W. McDarrah, courtesy of Steven Kasher Gallery.

I’m an artist who has been asked by a patron to do a room-size installation, filled with my sculptures, in some vacant space in the West Village. I’m excited at the prospect of trying something like this for the first time. I want to contract a friend in the printmaking world to do the wallpaper for it. Is there anything I should know about copyright when it comes to wallpaper?

Pattern design is an underrated art. Many people probably don’t realize that their favorite fashion brands employ professionals whose sole job it is to design the little detailing that runs down their sleeve. The same is true for the companies that make wallpaper, and even if these designers have signed away their individual rights to the company, you wouldn’t want to step on those toes, either.

Until recently, I would have suggested borrowing an obscure photograph as the basis for your wallpaper—the way Warhol did with his Cow Wallpaper—since the photographer (if they are still alive) would be unlikely to argue that your work has hurt the market for theirs in the same way a pattern designer might. But recently, we in the copyright community were handed the unique case of Judy Juracek vs. Resident Evil 4.

Juracek, a photographer, is suing the Japanese video-game company Capcom for borrowing from her 1996 book Surfaces: Visual Research for Artists, Architects,and Designers. Juracek alleges that Capcom used her photographs of Italian windows and bas reliefs to decorate the rooms the players explore in their video games. Some of the accusations are pretty damning, with one shattered pane apparently having been ripped off for a game’s logo.

I have not played a video game since Mario Kart, but I see clear parallels to your installation. What are the rooms in video games if not little art installations in which you kill zombies? The implications of this case could be wide, as it develops. I urge you to tread lightly, and ask for permission before you hang your own real-world wallpaper.