Know Your Rights

Can Two People Who Own the Same Art Print Both Mint NFTs of It? + Other Artists’-Rights Questions, Answered

Plus, is Tesla abusing copyright law by forcing YouTube to remove unflattering videos? And why is Le Tigre in trouble?

Plus, is Tesla abusing copyright law by forcing YouTube to remove unflattering videos? And why is Le Tigre in trouble?

Katarina Feder

Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

I read your answer to the question about museum-issued NFTs in last month’s column and I have a follow-up. The British Museum isn’t the only institution that owns a print of Katsushika Hokusai’s Great Wave Off Kanagawa. What if you’re one of the others and want to issue your own NFT based on it? What happens to the “uniqueness” of these items if all the owners start minting NFTs of the same work?

I love when this column becomes a conversation. Thank you, reader, for following up.

Too often in the discussions of NFTs, we forget that the NF stands for “non-fungible,” which is just a fancy term for “unique.” And what makes an NFT unique is not what it looks like. Rather, the thing that makes the NFT unique is its associated blockchain technology.

NFT pessimists often come to me baffled that someone spent north of $69 million on Beeple’s Everydays: the First 5,000 Days, when they can display an image of said work for free. All they have to do is go on the internet, Google the image, and viola! Same thing, right? Well, not really. What is unique about Beeple’s original is the fact that the image sits on a “non-fungible” piece of code that can always be tracked thanks to the blockchain.

This concept is actually pretty radical and the potential implications for creators are nearly endless. Assets in the analogue world have value—some real and some perceived. Value as ascribed by the art market is almost entirely perceived. A bar of gold is worth something in dollars. Unless you are an alchemist, you cannot create gold. Art, on the other hand, is a different story.

At ARS, we do a lot of licensing for T.V. and film, but if you see a Picasso on Succession, it’s almost certainly fake. These fakes are so good that we insist that they be sent to us for destruction after filming. In other words, they are basically identical to the original, but they are also without value, despite the originals being worth, yes, $69 million and beyond. The value is not based on the object’s appearance; it is based on the fact that we have designated it as the original.

So, to bring it back to the Hokusai: The work is out of copyright, so any museum that is in possession of the print—or anyone who could download the image online, for that matter—could create their own NFT of it. I’d wager that the British Museum’s NFT would probably be worth more than one that looks exactly the same, just made by hackerdude666. But this is a brave new world and I don’t say that with any certainty. Both are “unique,” just not to the bare eye.

Tesla CEO Elon Musk speaks during an event to launch the new Tesla Model X Crossover SUV on September 29, 2015 in Fremont, California. (Photo by Justin Sullivan/Getty Images)

I heard that Tesla is using copyright to force people to take down videos on Twitter that show their autopilot feature taking control of the car and not stopping for pedestrians. While I doubt that this is actually a copyright issue, I’m curious as to how they can argue this.

This isn’t terribly art-related, but I suppose Jack Dorsey did have an NFT, so…

If you aren’t familiar with this situation (I wasn’t before this question arrived), you can read up on it a little here. It’s worth exploring in this column because it involves the Digital Millennium Copyright Act, which aims to protect copyright holders from online theft and is being used (one might say weaponized) fairly liberally these days.

Someone who doesn’t know much about copyright might assume that these takedowns perhaps protect some sort of proprietary information about Tesla’s autopilot, but even if that were the case, that isn’t a copyright matter. Copyright law, in fact, expressly excludes copyright protection for “any idea, procedure, process, system, method of operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied.” I can’t blame YouTube and Twitter for being proactive in the face of potential litigation, but whatever is happening here has little to do with copyright, even if copyright is being used as an excuse.

If you can believe it, another controversial green automotive company, Nikola, has been using the exact same tactic to stop people posting footage of one of their electric trucks rolling down a hill. According to the Financial Times, a Nikola spokesperson blamed YouTube’s algorithms for the takedowns, while YouTube said that Nikola had flagged the alleged copyright violations themselves. The FT even notes that YouTube’s copyright rules say that “in the U.S., works of commentary, criticism, research, teaching, or news reporting might be considered fair use, but it can depend on the situation,” which suggests that they are as skeptical as I am that this is at all about copyright infringement.

Copyright is ultimately about the protection of human expressions that are truly original. These two companies would do well to remember that, especially since they’re both named after the exact same person.

Johanna Fateman of Le Tigre performs in support of the bands “TKO” release at the San Jose Civic Auditorium on July 12, 2005 in San Jose, California. (Photo by Tim Mosenfelder/Getty Images)

Imagine the pain I felt in my aging Gen X heart when I read that the women behind Le Tigre are being sued by the guy who wrote the original song “Who Put the Bomp (In the Bomp, Bomp Bomp),” famously sampled in “Deceptacon.” Who’s gonna sue them next, Megatron? How is this possible?

It’s true that such a lawsuit could deal a major blow to bars in the East Village that have PBR/shot specials. But if you’re lucky enough to be so young that you didn’t understand most of this question, allow me to give to a primer. Kathleen Hanna and Johanna Fateman’s Le Tigre was a late-’90s feminist pop rock/electronic band whose “Deceptacon” is described in their complaint as their “most popular song,” streamed 69 million times on Spotify alone.

Their complaint? Yes, you had it slightly wrong in your original question, my aging hipster friend. It is Hanna and Fateman who are suing the Bomper in question, 82-year-old Barry Mann of Beverly Hills, over his “frivolous but persistent legal threats.” “We don’t want to sue anyone, let alone another artist,” they told Pitchfork in a statement, “but we have no choice at this point. We just want Mann to leave us alone.”

In this non-lawyer’s opinion, their reference to his song is such a good example of “transformative use” that it harkens back to the case from which the term originates.

The concept of “transformative use,” of course, dates to a 1994 case involving a 2LiveCrew song, “Pretty Woman,” that had the rap group updating Roy Orbison’s “Oh Pretty Woman.” The song actually had little in common with Orbison’s song—aside from the sampled guitar lick— but what made the song truly “transformative” in the eyes of Supreme Court Justice David Souter, who wrote the opinion, was the Crew’s method of “substituting predictable lyrics with shocking ones” to show “how bland and banal the Orbison song” is.

Hanna and Fateman argue that they’ve done the same, citing music writer Sasha Geffen, who wrote that LeTigre took a “heteronormative love song” and “turn[ed] it into a rallying cry for feminine independence.” Mann’s song begins, ironically enough, with him saying, “I’d like to thank the guy who wrote the song that made my baby fall in love with me” and then, of course, asking, “Who put the bomp in the bomp bah bomp bah bomp? Who put the ram in the rama lama ding dong?”

Le Tigre’s version, the band’s complaint argues, asks the opposite of Mann’s question: “Who took the bomp from the bomp-a-lomp-a-lomp? Who took the ram from the rama-lama-ding-dong?”

Hanna and Fateman go on to accuse Mann of appropriating his own lyrics from Black doo-wop groups. But even without that argument, they have a very strong case. Commenting on something, or making a parody of it, is almost always fair use. Still, we look forward to the resolution of this case if only to determine the exact whereabouts of both the ram and the bomp.

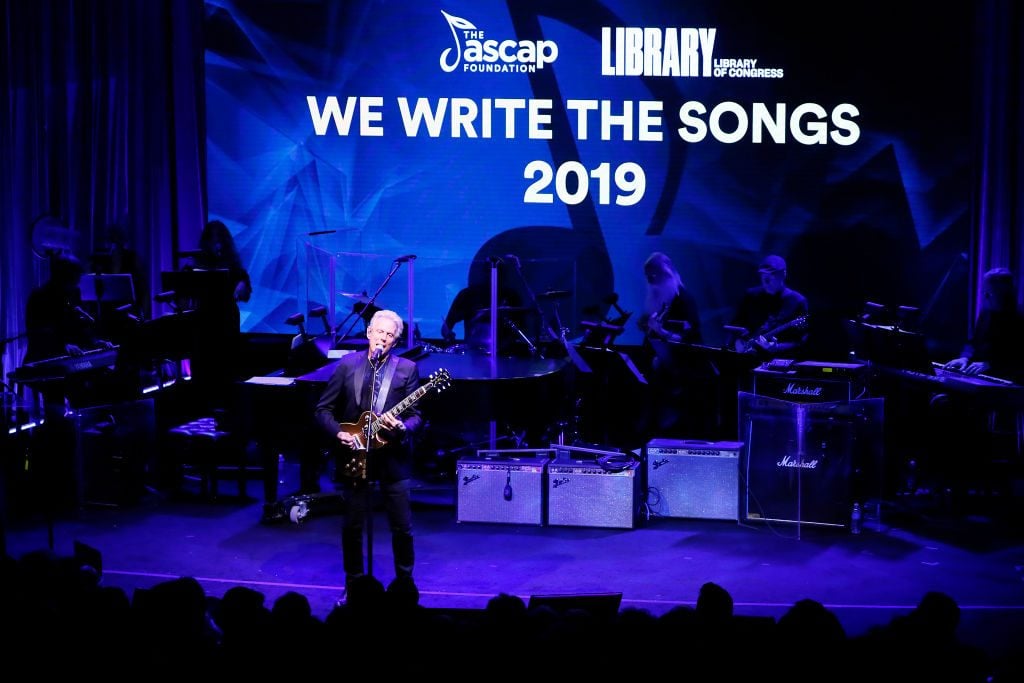

Don Felder of The Eagles performs “Hotel California” at the ASCAP Foundation’s 11th annual “We Write The Songs” event at the Library of Congress on May 21, 2019 in Washington, D.C. (Photo by Paul Morigi/Getty Images)

I saw that musicians are currently lobbying the Copyright Royalty Board for higher streaming fees. What is the Copyright Royalty Board and might visual artists somehow form one?

Actually, it’s music publishers who are lobbying the Copyright Royalty Board, and the distinction is important because what they do is different from what you do as an artist. But don’t get too disappointed about that because while the name sounds good, you probably wouldn’t want such a board as part of your professional life.

The Copyright Royalty Board is a federal three-judge panel that is technically a branch of the Library of Congress. It was established in 2004, but as this Wall Street Journal story points out, its origins lie in a 1909 act that targeted the makers of player piano rolls, whom Congress felt had an unfair sway over contemporary listening. To take away this perceived monopoly, they stipulated that such publishers must license their intellectual property, with the price determined by the government.

These days, the board sets the compulsory rates that Spotify, Apple, Pandora, and other streamers must pay to music publishers and songwriters (as opposed to performers or record labels) when users stream their songs. As with any flat fee, these royalties are a little thin. One of the numbers being thrown around for the increase is $0.0015 per stream, much more than they’re receiving right now.

I’m not sure what an equivalent for visual artists would look like, since the songwriter and performer roles are the same, in our world. If you’re looking for an organization that makes sure you get paid any time your work appears somewhere outside a museum or gallery, that’s more or less what we do at ARS. But we negotiate a unique price for each work and try to get our artists the best deal possible. Here’s hoping the songwriters of America are able to get their due someday as well!