Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

I am looking to get more information on the legal framework involved in helping local museums mint their art pieces as NFTs. My business supports a few local Italian museums and collectors of classic art and I would like to structure the service properly. Is there a clear methodology for how to do this while respecting all parties involved? We would like to proceed in a very clear, ethical, and legal way.

There’s almost no legal framework here—NFTs are just too new! But you aren’t the only one wondering. Several people also wrote to us about the British Museum, which recently minted NFTs based on the work of Katsushika Hokusai. Let’s address both matters here.

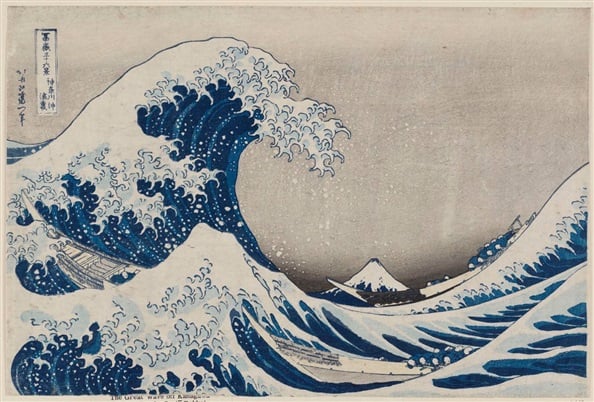

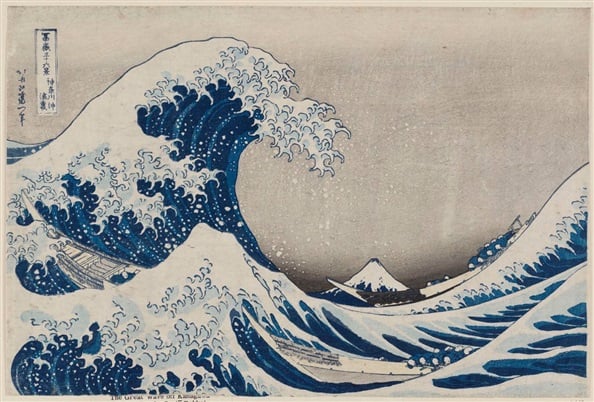

There are no laws or court decisions governing NFTs, but in the U.K. and Italy, as in most of the world, copyrights tend to expire 70 years after the death of the creator. Hokusai was a master of the Edo period and his influence on art history probably cannot be overstated, but he died in 1849. Therefore it’s legal for the British Museum to do almost anything they want with his work, and the same goes for anyone else, as exemplified by this iPhone case that rather bafflingly combines The Great Wave off Kanagawa and Starry Night. (RIP Vincent Van Gogh, 1854–1890.)

Katsushika Hokusai, Under the Wave off Kanagawa, (c. 1830–1831). Courtesy of the Museum of Fine Arts Boston and the artist.

I would guess that most of the “classic” art pieces in your clients’ collections are religious works from the Renaissance and the like, and are therefore probably not subject to copyright law at all.

A quick digression for a moment: I said that copyrights “tend to” expire 70 years after an artist’s death but there are notable exceptions, which explains why The Great Gatsby entered the public domain just this year despite F. Scott Fitzgerald’s having passed in 1940. I double checked a few things about British copyright law in preparing this edition of the column and found out that only two works from those isles have been granted “perpetual copyright”: the King James Bible and the theatrical version of Peter Pan (royalties for which are always payable to the Great Ormond Street Hospital for Children in accordance with the wishes of J.M. Barrie—isn’t that delightful?).

The British Museum has positioned its NFT project as a way to broaden appreciation of Hokusai. “NFTs have introduced a younger and more global audience to the art world, with Christie’s reporting that 73 percent of the registrants for their NFT auctions have never before bid at the auction house,” ARTnews wrote in its story on the initiative. I’m not certain I would cite bidders at Christie’s when trying to prove that a movement is youthful and diverse, but I will say that in my experience NFT purchasers are not the same people who collect physical art. These digital iterations are going to fund the museum and help it reach more people, and I think we can all agree that those are basically good things.

That’s the spirit that should guide your dealings. It’s not hard to be a responsible minter, just keep everything above board. Don’t only think about what’s legal, think about what’s right. Remember that this is about putting great works before new audiences, not making a quick buck, and I’m sure your partners will be happy.

I’m a video artist and a friend of mine recently turned a five-minute section from my work into a gif. It’s become semi-popular when you search for a certain popular noun on something called “Giphy,” a website with which I was not familiar, but which is apparently related to texting. Can I receive any money from this?

Probably not, I’m sorry to say. The main thing working against you here is the lack of transactions involved. If only Giphy charged a fee for every gif used (a thought I have often had while texting with those who use the file format a little overzealously).

While it’s true that Giphy was worth some $400 million to Facebook when it bought the company last year, no money changes hands when one of its billion gifs is sent each day. You just copy them, paste them into your iMessage, and leave it up to the nodding, 1972 Robert Redford to convey your emotions.

As with the NFT question, there is no case law here. But I think an instructive case study is what happened after The Mandalorian revealed the new Star Wars character Grogu, aka Baby Yoda. Giphy preemptively took the images down assuming that Disney would sue, but then put them back up again after an outcry from fans (and with the implied approval of Disney). Media companies are either embracing gifs as a new form of promotion or have come to peace with the fact that gif lawsuits probably won’t go very far. It is definitely remarkable whenever Disney opts out of a cease and desist.

Your case isn’t so different from that of Elissa Slater, a Big Brother contestant from North Carolina best known for doing a spit take of Sprite into a white coffee cup while wearing a teal top. Her reaction was turned into a gif that, this article estimates, has been seen more than three billion times. “I love the GIF myself. I like that people use it all the time and think it’s fun that it’s gone super viral,” she said. “I just wish I got paid for it.”

Jackson Pollock and Lee Krasner in Jackson Pollock’s studio (1950). Photo: Lawrence Larkin for the New York. Courtesy American Contemporary Art Gallery, Munich.

I’m currently pitching a TV show about the life and times of Jackson Pollock. To what extent do I have to worry about copyright issues?

I have no doubt about your project’s legitimacy, but I have to admit that your question reminds me of the 30 Rock storyline in which Jenna stars in an unlicensed Janis Joplin biopic for which they have no musical rights and ultimately must change her character’s name to Jackie Jormp-Jomp.

It’s a good joke that, as we’ve noted in this column before, is based in reality. Ava DuVernay’s Selma (2014), for example, is a Martin Luther King, Jr. movie without any real Martin Luther King, Jr. speeches in it. There’s one main thing that’s important to remember about copyrights when it comes to delving into the past for Hollywood-adjacent projects: You can’t copyright history—they could never actually make you change Pollock’s name—but you can copyright works of art or literature, and it turns out that’s almost the same thing.

Okaying works for the silver and streaming screens is a growing part of our business at ARS, and since the Pollock-Krasner Foundation is an ARS client, it is my duty to encourage you not to recreate his work using ersatz drips. You’ll likely have to go through us if you want to use any real photographs of the man, too, since likeness rights or personality rights would apply to actual images of Pollock (to say nothing of the copyrights held by the photographer).

Could you technically make this show without ever informing the folks who control Pollock’s estate? Possibly. But there are so many x-factors here I think it’s better to bring everyone on board as soon as possible. Last month, the Soviet-era chess champion Nona Gaprindashvili sued Netflix over her portrayal in the final episode of The Queen’s Gambit. In the show, someone describes her as “the female world champion [who] has never faced men,” but Gaprindashvili contends that by 1968, the year the scene was set, she’d actually faced 59. The show also calls her Russian when she is proudly Georgian.

This isn’t a copyright issue: Gaprindashvili’s lawsuit alleges “false light invasion of privacy and defamation.” But I bring it up because when you’re working with the real world, even a single tossed-off line can open you up to liability. Jackson Pollock led a heady and gossip-filled life. Do yourself a favor and contact the estate early and often.

The poster for Marvel’s What If…?

A friend of mine told me the Marvel movies will soon be declared illegal because of this lawsuit. Is that true?

At first I thought that you were going to link to the Scarlett Johansson suit, because that one (which settled last month) probably had a better shot of disrupting the Mouse House.

In fact, you linked to this lesser-known recent Disney lawsuit, which involves the original creators of Marvel superheroes such as Doctor Strange, Black Widow, Hawkeye, Captain Marvel, Falcon, Blade, and the Wizard. I am only familiar with about half of those but I am very familiar with the fascinating loophole that has allowed 89-year-old Lawrence D. Lieber, the estates of Steve Ditko and Don Heck, as well as the heirs of the writers Don Rico and Gene Colan to seek recompense here.

This is a noble cause. Even those with a passing familiarity with comics know that the creators of these superheroes weren’t fairly compensated for their work because in the days before mass merchandising, these were just funnybooks for children that cost 25 cents. Copyright rests with the maker from the moment a work is created, but turning over that copyright was often a condition of employment for these artists and writers. “We always felt ‘we wuz robbed,’ as Joe Jacobs, the boxing promoter, used to say,” said Joe Simon, the co-creator of Captain America.

I first read that quote in this excellent paper about the 2011 efforts of the heirs of Simon’s co-creator Jack Kirby to terminate his transfer of copyrights on 262 works to Marvel, which is useful here because Team Kirby used the exact same argument as the current lawsuit. They cited a clause in the Copyright Act of 1976, more or less the basis of modern copyright law, which allows a creator to terminate the transfer of rights that had been licensed out 35 years after the publication of a work. Disney’s Marvel countered that these were “works made for hire” and thereby ineligible for such termination. They won.

What are “works made for hire?” And for that matter, what is employment when you’re just drawing comics in your garage and receiving the odd check from a big building you’ve only visited a handful of times?

A 1965 case involving advertisements for a hardware store offers some guidance, suggesting that a work made for hire satisfies the following conditions: first, “the motivating factor” for its creation was inducement by the employer and second, “the employer [has the right] to direct and supervise the manner in which the writer performs his work.”

If you’re like me, you find that qualification unhelpful, especially in this era when we all have the option to work on Zoom at our kitchen tables. I doubt Disney is going to let go of an iconic hero like the Wizard (?) without a fight, but artists, graphic designers, and writers of all stripes should be watching this case with interest.