Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

There’s a lot of talk about the United States following India’s lead in banning TikTok over its alleged links to the Chinese surveillance state. My cousin happens to be kind of blowing up on TikTok, and it seems unfair that her future should be derailed by geopolitics. What happens to her videos if Trump bans the app?

First thing’s first: your cousin should start making an offline archive of whatever she does to garner hits. (Pointing at household objects while pop songs play in the background, perhaps?)

From a copyright standpoint, social-media apps have always had terrible end-user license agreements, and we’re still learning just how bad they can be. Earlier this year, Judge Kimba Wood of the Southern District ruled that Instagram reserves a “non-exclusive, fully paid and royalty-free, transferable, sub-licensable, worldwide license to the content that you post on or through” Instagram, quoting with those words the user contract that we all agreed to when we signed up. That was a very specific case wherein Mashable embedded a photographer’s picture from Instagram after she rejected their offer to license it, and Wood herself later reversed her own decision after some of those facts came to light. But the takeaway is clear: you do not own anything you post on Instagram, and if you post an image you do own, it’s possible it may be used in ways you do not approve of.

If all this strikes you as unfair, especially if you are an emerging artist sharing your work online—well, then, you and I have a lot in common. But, like it or not, Instagram is considered a place where art happens now: a place where it is shared, discovered, and even bought and sold. So most artists interested in promoting their work online will have to kiss the Zuckerbergian ring.

Which is all to say: if your cousin is smart, she will get an external hard drive—and sign a placement deal to start pointing to Coca-Cola products in her TikToks. She could end up the next Justin Bieber (discovered on YouTube) or Shawn Medes (found on the now-defunct Vine). Apps may come and go, but the pursuit of fame is perennial.

A protest at the Whitney during the museum’s Andy Warhol show. Photo: Ben Davis.

I’m a Black artist. If my work were to be shown at one of New York’s fine institutions with more questionable board members, what could I do to stop that?

The boards of museums inspire strong feelings in artists and visitors alike. Even before the killing of George Floyd set off a reckoning over equity and employee treatment in America’s museums, many institutions had been forced to confront the fact that some of their top patrons had ties to unsavory sources of wealth.

Everyone has their own set of morals and boundaries when it comes to this stuff, and you should absolutely feel comfortable voicing your concerns or even requesting to pull your work. That said, technically, a museum is free to exhibit an artwork that it owns even without an artist’s consent.

According to the Association of Art Museum Directors’ guidelines for the use of copyrighted material by art museums, “the right to such display is conferred on the owner of the original work… without the authority of the copyright owner… The display right is the lifeblood for museums and finding examples in which copyright owners have challenged a museum’s right to display works of art owned by the museum or on loan to the museum is extremely rare.”

Still, if a museum were to use your work without permission and you wanted to make a statement about it, there would be precedent. Artist Cady Noland has spent much of her career disavowing works that she no longer wants attributed to her because of the way they have been displayed or restored.

That said, if you still own the physical work and have been asked to lend it to an institution, you may of course refuse to do so for any reason—including if you object to the composition of its board. Good luck.

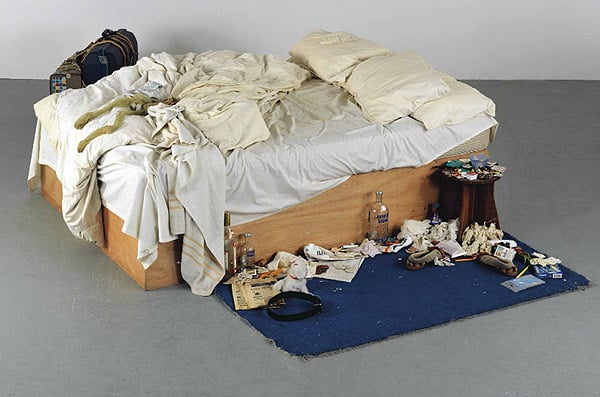

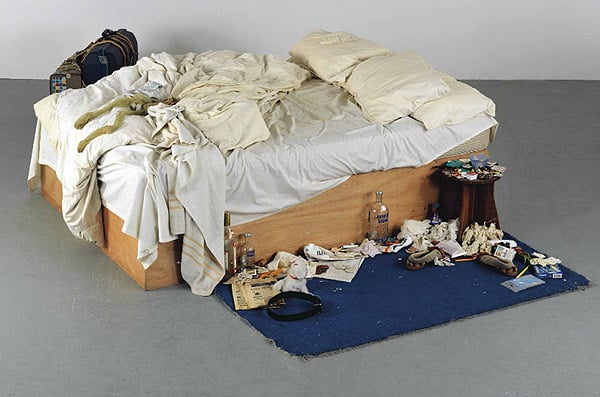

Tracey Emin, My Bed (1998). Courtesy of the Tate.

I’ve been housebound in my New York studio, thinking about ‘90s art. I couldn’t help but wonder: how could Tracey Emin’s My Bed (1998), be copyrighted? Especially since the work does not remain consistent over time?

Who among us has not been housebound in a New York studio, thinking about ‘90s art ranging from Tracey Emin to Nirvana to Clueless? As if, indeed.

If you aren’t aware of the English artist’s seminal work My Bed, let me catch you up: A touchstone of the YBA (Young British Artists) movement, it comprised Emin’s messy bed, complete with unlaundered, rumpled sheets, cigarette butts, discarded condoms, and blood-stained underwear. It was a prime example of the “my kid could do that” aesthetic that defined much of the decadent ‘90s. (When someone addressed this criticism to Emin, she replied, “Well they didn’t, did they?”)

When the Turner Prize-shortlisted work debuted at the Tate in London in 1999, lines formed around the block. It went on to sell at Christie’s in 2014 for £2.2 million (over $4 million at the time).

Part of the work’s appeal is that it is different each time it’s installed. And so, my astute questioner, we come to the crux of your inquiry: given that copyright normally applies to artworks that are “fixed in tangible form,” does it cover each variant of My Bed? Is there some Platonic ideal of the work?

I would argue that My Bed is somewhere in between an installation and a performance—neither of which is fixed, and neither of which enjoys much by way of copyright protection. (The US Copyright Office generally discourages applicants from using the term “installation art” because “the term is unclear,” and performance art has almost no protection, or even legal definition.)

But in 2008, the UK’s Supreme Court made a copyright ruling that may be relevant here. The case involved Lucasfilm, which sued a manufacturer of replica props and costumes from the Star Wars movies. In his ruling, the judge referenced Carl Andre’s Equivalent VIII (1966), itself the subject of much British controversy. He wrote:

A pile of bricks, temporarily on display at the Tate Modern for two weeks, is plainly capable of being a sculpture. The identical pile of bricks dumped at the end of my driveway for two weeks preparatory to a building project is equally plainly not. One asks why there is that difference, and the answer lies, in my view, in having regard to its purpose. One is created by the hand of an artist, for artistic purposes, and the other is created by a builder, for building purposes.

Put simply, per the judge, Emin’s intent is what distinguishes her bed from yours. So you may as well go ahead and tidy the accidental tribute crowding your studio.

Installation view of “Sol LeWitt: Lines, Forms, Volumes, 1970s to Present,” 2019. Courtesy of Galleria Alfonso Artiaco.

I’m getting ready to list my New York City apartment for rent (or potentially even sale!) and it occurred to me that I should double check something: a couple of years ago, I put up a wall drawing “by Sol LeWitt,” hiring an artist to follow his instructions—although this was just for my private amusement. Are there any problems associated with my renting or selling this place?

For those who are not familiar, Sol LeWitt was a hard-core conceptualist who believed that the mere idea of a work constituted art itself. He turned his concepts into sets of instructions—like an architect’s blueprint or a musical score—and enlisted other people to create the physical work of art. While a bona fide LeWitt only exists with a certificate of authenticity, you can certainly follow the same instructions to create a convincing knockoff.

There’s nothing wrong with this drawing’s existence in your apartment. You—and your renter/buyer, for that matter—are free to enjoy the work with your morning coffee. Nevertheless, I would advise your realtor to do some Photoshop on the walls to obscure the drawing before you list your apartment online.

Why? If you include photos of your LeWitt interpretation in the listing, you are using the work for a commercial purpose, i.e., to solicit a renter or buyer. And every time you reproduce a copyrighted work, you are obligated to seek approval from the artist or estate.

Now, this wouldn’t be an issue if the work weren’t in situ—but since it’s a part of the apartment, its value affects the apartment’s value. When you put photos of your apartment on Airbnb or StreetEasy, the work has left the realm of personal amusement and becomes an advertisement for your place.

To avoid any potential headache, have the wall Photoshopped for the listing photos. Remember, the art may be conceptual, but the consequences could be very real.