Law & Politics

Cady Noland Said a Collector Restored Her Log Cabin Sculpture Beyond Recognition. A Judge Has Thrown Out Her Lawsuit—for the Third Time

The judge doubles down on two previous rulings.

The judge doubles down on two previous rulings.

Eileen Kinsella

The third time does not appear to be the charm for Cady Noland. The elusive and sought-after artist has proven unsuccessful in a lawsuit—her third such attempt—arguing that a German dealer, a conservator, and an art advisor created an unauthorized copy of her work.

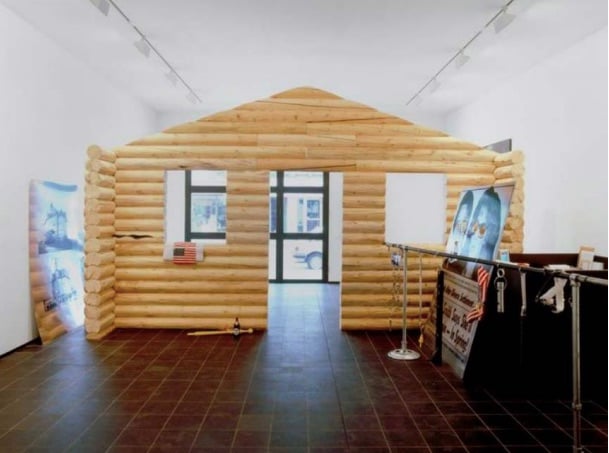

The long-running case raised questions about what makes a work of art unique, what a collector is or isn’t allowed to do with art he owns, and at what point conservation becomes tantamount to creating an entirely new object. The latest ruling, filed in federal court in the Southern District of New York on June 1, failed to address some of these thorny questions, but did determine that the refurbishment of Noland’s work Log Cabin did not violate her rights as an artist or infringe on her copyright.

Noland’s lawyer, Andrew Epstein, told Artnet News that the court erred in its decision and that his client is pondering yet another appeal.

The dispute over the work stretches back to 1995, when Log Cabin‘s owner, collector Wilhelm Schürmann, loaned the work to a museum in Aachen, Germany. After several years on display outdoors, the wood began to rot. Conservators replaced the original components with new logs sourced from the same Montana manufacturer that Noland used for the original.

Schürmann later worked with several galleries and private dealers to sell the work to Ohio art collector Scott Mueller for $1.4 million. The sales contract, however, included 12-month buy-back option should Noland, known for her controlling nature, disavow the work—which was exactly what happened after she learned of the work’s conservation.

A lawsuit brought by Mueller over the refund was dismissed by a judge in December 2016. But Noland filed her own suit in July 2017. Subsequent legal battles devolved into a dispute over where the artist had the right to sue (the US or Germany), and therefore which laws and rights apply to her.

A photograph of Log Cabin attached to Cady Noland’s third complaing. Image via Pacer

Judge Oetken ruled that Noland’s rights were not violated under the Visual Artists Rights Act or the US copyright act because the restoration took place in Germany, not America. The judge was not convinced by Noland’s argument that the fact that the wooden replacement components were purchased from a Montana manufacturer should mean that US law applies because the purchase of the wood “is not independently an act of infringement.”

Oetken also noted that the failure of Noland’s argument was compromised not only by location, but also by timing. The creation of the original Log Cabin façade predates 1990, when VARA went into effect, so the original work does not qualify for the statute’s protection, he wrote.

In a statement, Noland’s lawyer contended that the court failed to consider the fact that photographs of the altered work were distributed and used to facilitate its sale in the United States. “While the United States cannot enforce violations of German laws in the U.S., the distribution of photographs of the unauthorized copy of Log Cabin Façade (which was illegally fabricated in Germany) violates the United States Copyright Act,” Epstein said.

“The opinion is as interesting for what it doesn’t say as what it does say,” attorney Megan Noh, who represented most of the defendants, told Artnet News. “The notion that conservation can be ‘prejudicial,’ as asserted by Noland, to a living artist’s honor simply by virtue of having been undertaken without his/her permission is important and provocative in the context of the current art market. Many conservators do, as part of their practice, consult with living artists about planned conservation, but I am unaware of any case precedent establishing that failure to do so is, alone, ‘grossly negligent’…or otherwise actionable.”

In other words, it remains unproven if you can successfully sue a collector or conservator for conserving your work without your permission. And in Noland’s case, her bid to make the case appears to, at least for now, have come to an end.