Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, extending the art business into the afterlife…

PHANTOM THREAD

On Tuesday, the New York Times Magazine published Mark Binelli’s deep dive into the weird, wild world of dead music stars “touring” as holograms. And if this same technological (and entrepreneurial) innovation doesn’t cross over into the art market in the coming years, I’ll be so stunned that my own heart just might give out.

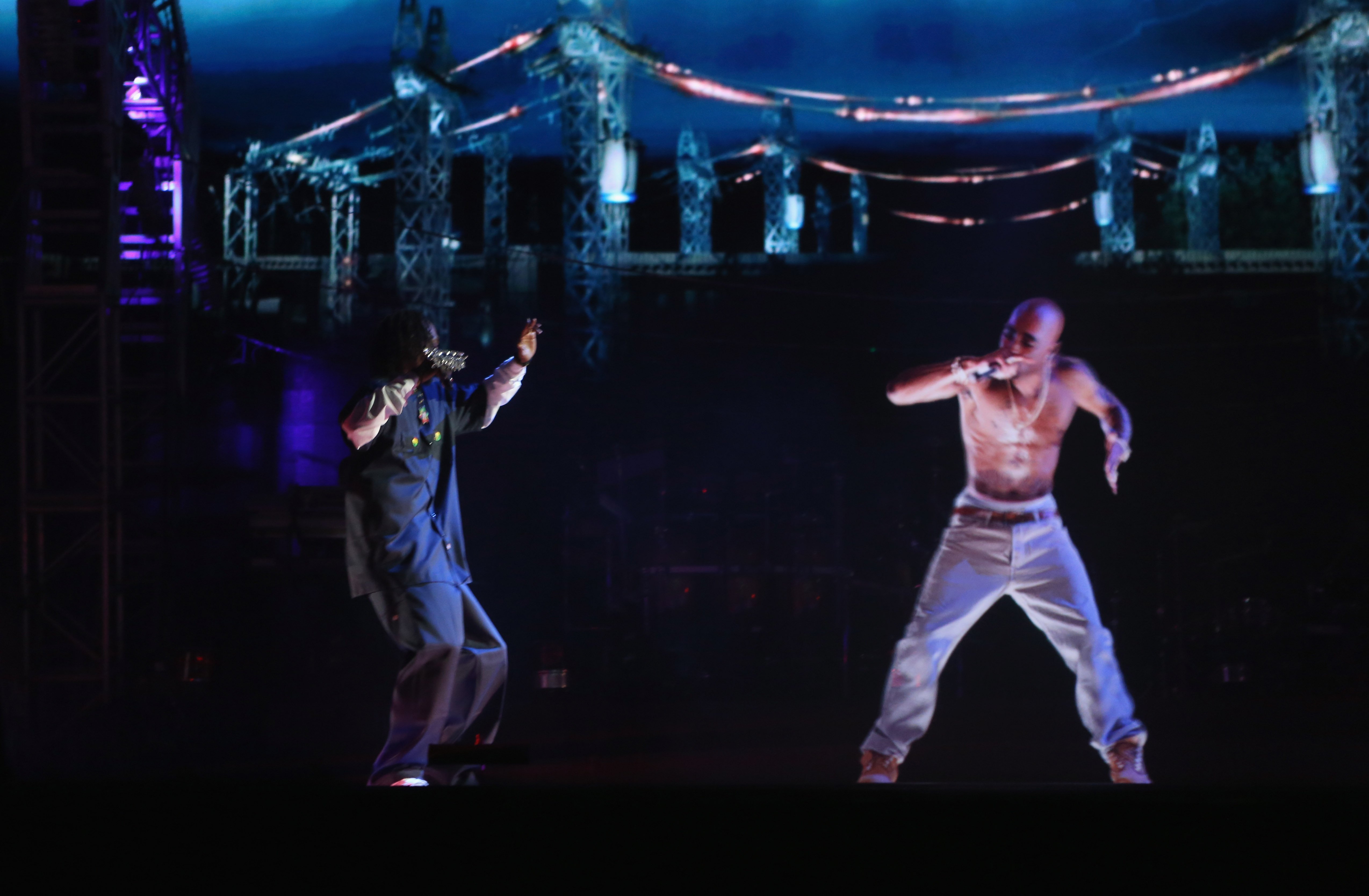

For the uninitiated, this surreal new chapter in pop stardom essentially began at the 2012 edition of Coachella, the annual pop-culture-shaping music festival in California’s Indio Valley, when visual-effects studio Digital Domain created a three-dimensional hologram of slain rapper Tupac Shakur that “performed” a pair of of his songs onstage with Snoop Dogg (whose metamorphosis from west-coast-rap firebrand and murder-trial defendant into middle-aged lifestyle guru and Martha Stewart bestie is more mind-blowing than any VFX I’ve ever seen).

Although Digital Domain went bankrupt shortly after the festival, Pac’s digital ghost—along with the good old-fashioned power of the dollar—dynamited the gates to the musical hereafter. A slew of new venture-backed businesses rose up to begin crafting holograms and striking pacts with artist’s estates for the rights to represent late stars onstage, in both senses of the word “represent.”

In the years since, the list of dead pop icons who have re-materialized for adoring fans includes Michael Jackson (at the 2014 Billboard Music Awards), Buddy Holly, Roy Orbison, Frank Zappa, Ronnie James Dio (who replaced Ozzy Osbourne as Black Sabbath’s frontman and enabled one very metal auction), and even legendary opera singer Maria Callas. And if you think this phantom express is slowing down anytime soon, I would advise you to get the hell off the tracks; a hologram of Whitney Houston will set out on an international tour starting in February.

Although this situation sounds absurd, the most stunning aspect may be that, based on the early returns, it appears to be absurd in the same way that selling milk from an almond once was. Here’s Binelli:

Deborah Speer, a features editor at Pollstar, which covers the live-entertainment industry, told me that based on the numbers she has seen for the Orbison and Zappa tours, “obviously, there’s a market” for hologram shows. According to the trade publication, the solo Orbison tour grossed nearly $1.7 million over 16 shows, selling 71 percent of the seats available, while Zappa sold an average of 973 seats per show, nearly selling out venues in Amsterdam and London.

It turns out that if you’re a famous performer, you don’t need to be drawing breath to draw a paying audience. And that apparent fact is emerging at an especially opportune moment in contemporary art.

Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present (2010). Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery,.

ALL THE (ART) WORLD’S A STAGE

Now, plenty of painters, sculptors, and other makers of discrete objects continue selling briskly even after they’ve died; their corporeal absence creates little to no drag on business (sometimes, it boosts it). But historically, we haven’t been able to say the same for performance artists. And this is especially important given the strong gravitation toward live art by artists, industry insiders, and even the general public over the past decade.

As my colleague Ben Davis argues, the inflection point was Marina Abramović’s “The Artist Is Present,” the zeitgeist-puncturing 2010 retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. The show certainly didn’t elevate performance art beyond parody—see Fred Armisen’s mockumentary TV series Documentary Now! or Ruben Östlund’s festival-conquering film The Square—but it did propel the genre to a level of familiarity that made it a justifiable, sometimes loving, touchstone for an audience outside the traditional art world.

For every satire, there also seemed to be at least one earnest celebrity homage that lodged performance art deeper in the popular consciousness. Fans include hip hop mogul Jay-Z, actor/director/artist Shia Labeouf, runway-rap pioneer A$AP Rocky, John Cheever’s favorite indie-rock band, the National… the list goes on.

Enthusiasm for artists or trends within the art world hasn’t always tracked with enthusiasm outside it. The tired specter of the “sell-out” keeps haunting us. However, the recent trajectory of performance art has avoided this turbulence.

Judges at the last two Venice Biennales awarded top prizes to performance works: Anne Imhof’s Faust won the Golden Lion in 2017, and the Lithuanian Pavilion’s climate-change opera Sun & Sea took home the trophy for best national presentation in 2019.

Mega-gallery Pace is making a high-stakes live-performance program a central pillar of its mainstream-targeting future strategy. And although MoMA eventually scrapped the performance-focused “Art Bay” once set to be the nucleus of its latest renovation, New York’s newest (and most controversial) cultural space, the Shed, largely exists to champion the genre.

All of the above (and much more) reinforces that performance has become a major force in contemporary art’s evolution, and will continue to shape its future. Which leads us back to those hologram tours.

A hologram of dead opera star Maria Callas “singing” onstage during a concert at Berlin’s Admiralspalast in 2019. (Photo by Frank Hoensch/Redferns)

BREAK ON THROUGH TO THE OTHER SIDE

Pop-star holograms are exploding out of a chemical reaction between three elements that have been influencing human decision-making for thousands of years: supply, demand, and survival instinct.

Binelli points out in the Times that, per Pollstar, “roughly half of the 20 top-grossing North American touring acts of 2019 were led by artists who were at least 60 years old,” including the top three: the Rolling Stones, Elton John, and Bob Seger. His conversation with a member of one major hologram-production company suggests this technology could transform those data points from evidence of an imminent music-industry crisis into evidence of an enduring business opportunity:

“If you’re an estate in the age of streaming and algorithms, you’re thinking: Where is our revenue coming from?” Brian Baumley, who handles publicity for Eyellusion, told me. Some of those estates, Baumley bets, will arrive at a reasonable conclusion about the dead artists whose legacies they hope to extend: “We have to put them back on the road.”

The art industry has just as much of a stake in extending the legacies—and profit windows—of major talents approaching (or past) the ends of their productive lives. By this point in time, the interplay between aesthetic evangelism and financial opportunism has been incentivizing choices within artists’ studios and estates for over a century, with each project finding its ethical level based on weighing those two factors.

Consider that every single plaster, bronze, or marble cast by Auguste Rodin was actually fabricated by another skilled artisan using only Rodin’s small clay models. Or that the Dia Art Foundation and the artist’s estate (with funding from Gagosian) completed Walter De Maria’s installation Truck Trilogy four years after his death. Or that the estates of Roy Lichtenstein and Constantin Brancusi both produced new editions of important sculptures decades past the dates their respective creators beamed up to that big studio in the sky.

Assuming performance art’s popularity surge continues, then, why wouldn’t a major gallery and/or institution be tempted to restage, say, the centerpiece of Abramović’s “The Artist Is Present” via hologram for a paying audience? Abramović herself might—might—be appalled by the idea as she lives and breathes now, but anything can happen when opportunities present themselves to estate executors.

After all, visitors to the Dalí Museum in St. Petersburg, Florida can already interact with a ghost of its namesake digitally resurrected on flat screens throughout the institution.

Joan Jonas performing Reanimation, still from Art21 “Fiction” (2014). Courtesy of Art21.

The potential here isn’t limited to postmortem programming, either. Holograms could also be used during performance artists’ lifetimes to stage their pieces farther, wider, and more frequently than if they had to physically make the trips themselves.

Precedents already exist for this. Binelli mentions in his piece that Chicago drill-rap standard-bearer Chief Keef performed by hologram at an out-of-state music festival to avoid arrest while he had active warrants looming over him in 2015, and Indian prime minister Narendra Modi has campaigned by hologram in multiple locations at once for years.

Obviously, these possibilities are only possibilities right now. But they are made more likely by the music industry’s rush to embrace—and monetize—hologram technology to overcome its biggest stars’ deaths.

Continued public demand for performance works will only increase the pressure on the art industry to follow suit in the future. And if the genre’s most physically punishing works have taught us nothing else, it’s that we should never underestimate humanity’s ability to transcend the seemingly impossible.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: whether the result is a hologram, a painting, or a kid, anyone who creates anything is on some level trying to beat the reaper.