Opinion

The 100 Works of Art That Defined the Decade, Ranked: Part 4

In the final installment of this four-part series, our critic reveals his picks—number 25 through number 1—of the key artworks of the 2010s.

In the final installment of this four-part series, our critic reveals his picks—number 25 through number 1—of the key artworks of the 2010s.

Ben Davis

This is the fourth part of a series looking at the art of the 2010s. The first three parts are here, here, and here.

A mysterious beast sighted in Meow Wolf’s The House of Eternal Return. Image: Ben Davis.

Partially funded by George R.R. Martin (who now serves as its “chief world builder“), the art collective Meow Wolf’s installation environment/fun house in Santa Fe, complete with secret passages and a labyrinthine back story, has quickly exploded into something that has slipped out of the category of art and into a whole other new thing. In the brief years since the debut of the House of Eternal Return, the “Meow Wolf Model” has quickly spread, with the group opening massive, multi-million-dollar environments in other cities.

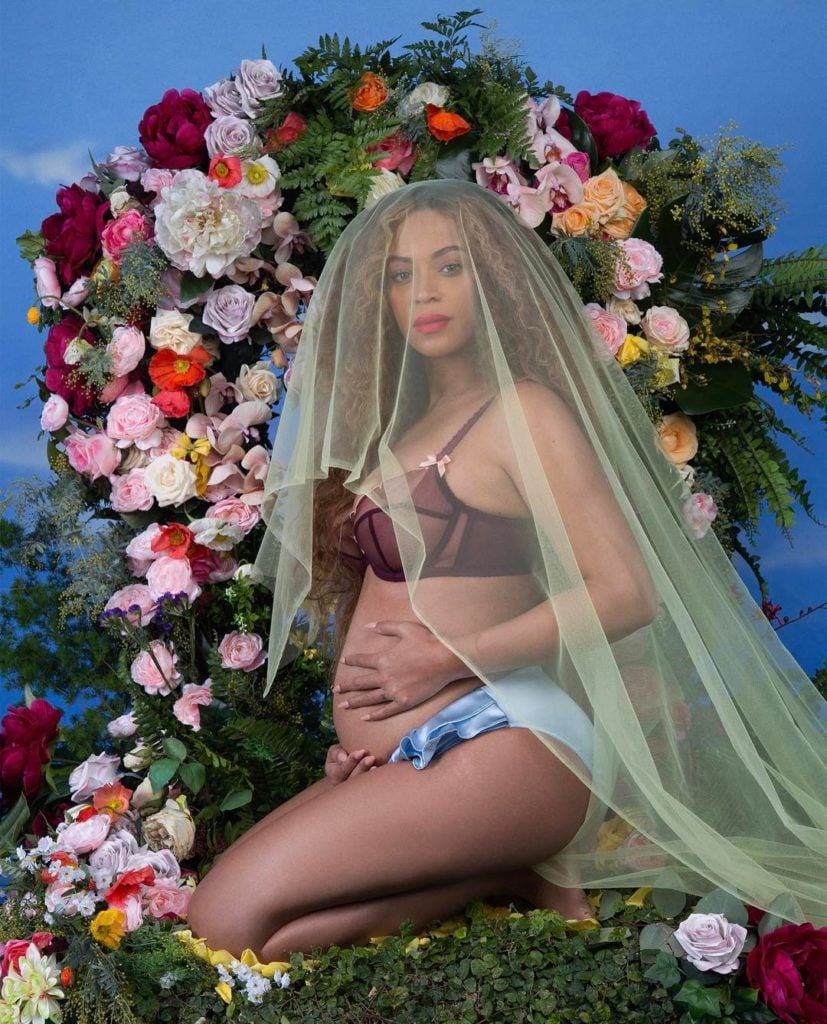

Awol Erizku’s Beyoncé pregnancy announcement photograph. Photo via Instagram.

Erizku himself is loathe to talk about his flower-bedecked portrait with Beyoncé, which was posted to her Instagram as the occasion for her to reveal that she and her husband had been “blessed two times” with twins. But with 11 million likes, it is one of the most viral individual artworks of all time, and definitely augured a new kind of symbiosis between celebrity, social media, and art.

Sotheby’s employees view Love is in the Bin by Banksy. Photo by Jack Taylor/Getty Images.

I don’t blame you if you are sick of Banksy. But, you know, the street artist’s self-destructing work of art, which surprised everyone by shredding itself via a trick frame at the climax of a Sotheby’s sale, is just outright hilarious and unexpected. Nothing like it had ever happened before and nothing like it will happen again.

A real touchstone work about artists’ search for community, queer solidarity, class, immigration, and a lot more, focusing on Silver Platter, an LGBT LA bar—which becomes a literal character in the film, with a voiceover ventriloquizing its thoughts—and the events that ensue when Tsang and a group of young, queer artists of color organize a performance party, the titular “Wildness,” in the space.

Installation view of Sheila Hicks, Escalade Beyond Chromatic Lands (2016–17), at Biennale di Venezia, Venice, Italy, 2017. Photo by Andrea Avezzù. Courtesy of La Biennale di Venezia.

The climax waiting at one end of the Arsenale space during the 2017 Venice Biennale (and recreated whole at the Bass Museum), Hicks’s great vertical accumulation of colored pom-poms made the case for the sheer breadth of her textile art’s ambition and ability to hold attention. “This is about massive amounts of color and how it affects its neighbors,” Hicks explained.

Reenactors retrace the route of one of the largest slave rebellions in U.S. history on November 09, 2019 in New Orleans, Louisiana. Photo by Marianna Massey/Getty Images.

A pointed rejoinder to generations of Civil War reenactments, Dread Scott’s deeply researched mass recreation of the German Coast Uprising of 1811, aka “America’s largest slave revolt” (with an alternate ending), featuring hundreds of volunteers, probably permanently pushed a piece of history that had been literally stamped out back into the light.

The lead photo “Paddy Field” for the exhibition “Crossfire: An Installation by Shahidul Alam on Extra Judicial Killings.” Image courtesy Shahidul Alam/Drik/Majority World.

As a teacher and activist, Alam is a giant, infamously having been detained in 2018 by the government in Bangladesh for comments he had made that ran afoul of draconian laws. It was not his first time. In 2010, his “Crossfire” series also got him in serious hot water, with the show shuttered by authorities at the time of its debut. The series recreates the supposed sites of so-called “crossfire killings” by the government’s Rapid Action Battalion, an anti-crime task force whose extrajudicial violence has been the subject of international scrutiny. Working with researchers, Alam made images that serve the purpose of pointing out inconsistencies in official accounts (e.g. a field that appears undisturbed despite having been reported to be the site of a fierce struggle) but that also have a forensic clarity and eery vividness that makes them difficult to forget.

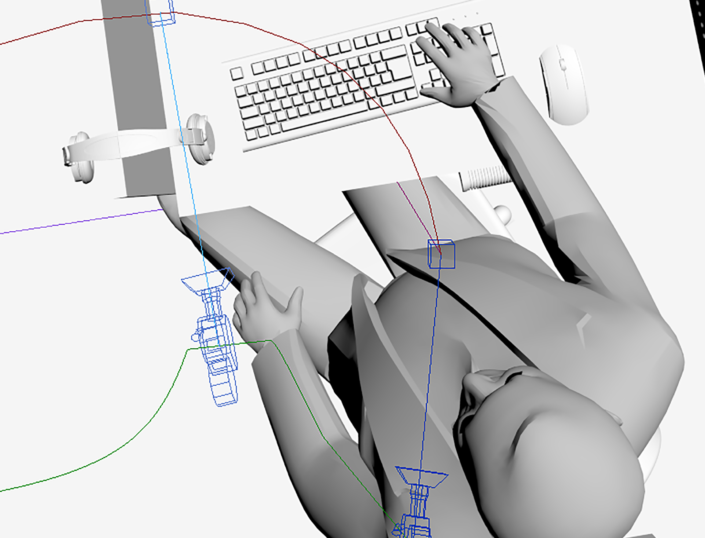

Poster for Community Action Center.

A three-year labor of love in every sense of the term, the traveling Community Action Center installation was, as Burns explained, an effort “to make a space for women and trans bodies to watch sexual content together, as well as to counter the way porn is now consumed on the personal computer.” The film itself doubles as document of and for a certain community and an experiment in utilizing the physical spaces of art to create a temporary autonomous zone for queer connection.

Installation view of Mark Bradford’s Pickett’s Charge at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Gardens, 2017. Photo by Cathy Carver, courtesy of the artist and Hauser & Wirth.

Some 400 feet long in all, Bradford’s sweeping series of murals has tremendous verve. Made from cutting and tearing up images of the battle of Gettysburg, it packs a heck of a lot of gravitas into a turbo-charged abstraction.

Wael Shawky, Cabaret Crusades: The Path to Cairo (2012). Courtesy the artist and Sfeir-Semler

Gallery Berlin/Hamburg.

This cycle of films captures the Crusades in all their glory, or infamy, through Arab eyes (it is based on the work of Lebanese historian Amin Maalouf). The fact that the tale is told with puppets—the first episode alone features more than 100 antique marionettes—may sound trivializing, but the choice allows for the telling of a story huge in scope, makes vivid another time in a way that shocks you out of your received images of it, and lures you in for something that is both really moving and really perspective-shifting.

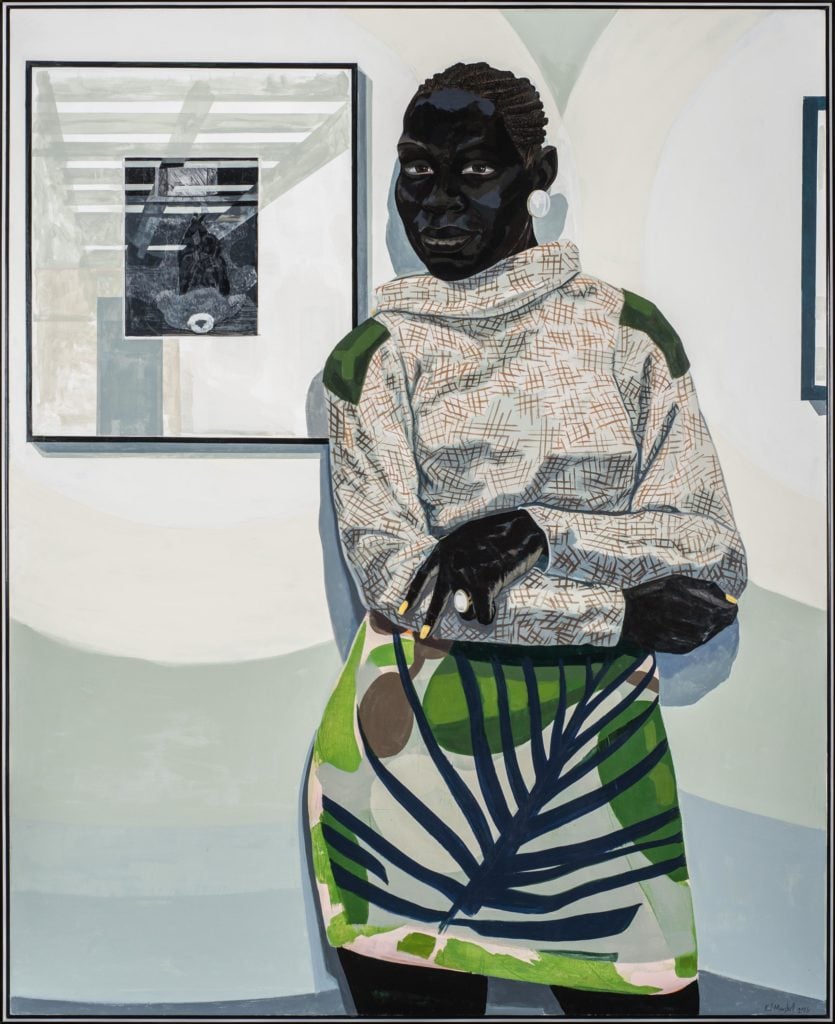

Kerry James Marshall, Untitled (Gallery) (2016), Carnegie Museum of Art. ©Kerry James Marshall, Courtesy the artist and David Zwirner, London

Kerry James Marshall emerged in the 2010s as a major, powerful force in contemporary painting, and his touring retrospective, “Mastry,” was much-loved. You could certainly pick any number of his amazing images as “best-of” material. This stylish five-by-four painting stands as a literal invitation for black museumgoers to claim the galleries. It was acquired by the Carnegie Museum, amid much hype, the year it was painted, and featured in “20/20,” a show it organized with the Studio Museum the following year.

This two-mile-long, temporary monument composed of 26 tethered balloons bearing the “open eye” symbol and bridging Douglas, Arizona and Agua Prieta in Sonora, Mexico is meant as an image of both trans-border connection and the persistent vitality of Native cultural power. For the curious, some sense of the massive effort and community-building that went into the piece—and which is definitely part of the piece—comes in the form of the documentary about its making.

A counter investigation into the murder of Halit Yozgat. Courtesy Forensic Architecture.

Ai Weiwei, Sunflower Seeds in the Tate Modern Turbine Hall. Courtesy of Tate.

Created before his detention by the Chinese government made him an international cause célèbre, Ai’s Turbine Hall commission probably marks the absolute apex of his work as an installation artist. The vast bed of individually crafted porcelain sunflower seeds showed off all the artist’s innate skill for public engagement, while also lending itself to complex thoughts about art and labor in a global world and reclaiming a sense of the individual within the collective.

John Akomfrah, The Unfinished Conversation (video still) (2012). Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy the artist; Smoking Dogs Films; Lisson Gallery.

The Unfinished Conversation is less poetic that other Akomfrah works such as the stunning Vertigo Sea, but it’s the work that seized me by my collar and told me to pay attention when it was shown as one of MoMA’s new acquisitions. A three-channel experimental documentary about the life and work of Stuart Hall, the activist, theorist, and founder of “cultural studies,” it offers a personal, lived-in history that uses its form to give a sense of a life lived straddling multiple worlds.

Marina Abramović, The Artist is Present (2010). Courtesy of the artist and Sean Kelly Gallery.

Also known colloquially as “the staring contest,” Abramović’s marathon performance as part of her retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in 2010 changed the status of performance art in the media imagination, from something that was essentially esoteric, difficult, and kind of the butt of a joke (à la Maude Lebowski in The Big Lebowski) to something that was glamorous, popular… and still often the butt of a joke, but a different kind of joke now.

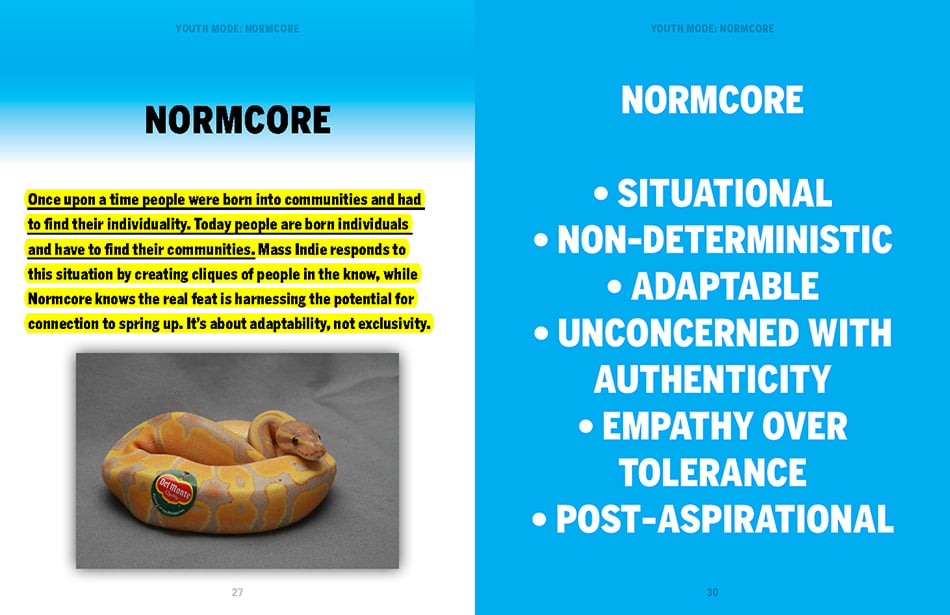

A page from K-HOLE’s Youth Mode: A Report on Freedom (2014).

Founded by Greg Fong, Sean Monahan, Chris Sherron, Emily Segal, and Dena Yago, the art collective K-HOLE defined a new potential mode of operation for artists—as satirical branding agency—which, in an astounding turn, actually broke out to affect the language of the culture at large. Released at the Serpentine’s 89Plus Marathon, the “Youth Mode” report was essentially an art parody of fashion futurology, looking at how you can carve out a sense of difference in an age when “be different” is the norm, hitting upon the idea of “normcore,” which went on to enter the popular lexicon, unironically.

Eliza Douglas in Anne Imhof’s Faust at the 2017 Venice Biennale. Photo courtesy of Vincenzo Pinto/AFP/Getty Images.

The most-talked-about event of the 2017 Venice Biennale was Imhof’s severe performance-art environment, which featured dogs, vacant-eyed performers, and a glass floor beneath which parts of the miasmic five-hour action took place. The blurring together of audience and performer, and of an arch, clearly fashion-derived affect with an unsettling sense of human beings malfunctioning, strikes me as reflecting a very contemporary purgatorial feeling.

Hito Steyerl, Factory of the Sun (2015). Installation view at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo. Photo: Eduardo Piva.

Hard to explain, so let me allow the official explanation to do it: Factory of the Sun “tells the surreal story of workers whose forced moves in a motion-capture studio are turned into artificial sunshine.” Steyerl’s experimental style of theoretical writing exploring the consequences of the collision of technology, art, and rapacious digital capitalism (collected in her 2017 book Duty-Free Art) has surged into the center of discussion in recent years. This funny and disorienting sci-fi narrative, which started out at the 2015 German Pavilion of the Venice Biennale and then took over museums in the years thereafter, was probably the best translation of her theoretical sensibility into lasting images.

Lina Lapelytė, Vaiva Grainytė and Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Sun and Sea (Marina) (2019). Performance, Lithuanian Pavilion at the 58th Venice Biennial, May 11 – October 31, 2019. Photo by Laima Stasiulionytė.

While an opera about climate change may sound like a very Portlandia idea, Sun and Sea (Marina) actually worked. Staged with performers presented lallygagging on a beach and singing reflectively from a future vantage point on life in a blighted world, the work—presented most recently in the Lithuanian Pavilion at the 2019 Venice Biennale—was art for the age of “climate grief.” Its taking of the Biennale’s top prize probably marks the arrival of the subject at the very center of art.

Exhibition view of “Kate Crawford, Trevor Paglen: Training Humans” Osservatorio Fondazione Prada, through Februrary 24, 2020. Photo by Marco Cappelletti, courtesy Fondazione Prada.

A team-up between an artist and a computer scientist, ImageNet Roulette was both an art installation and an intervention into the debates about the ethics of facial-recognition software. After it went viral, it actually caused a kind of modest real change, with the scientists behind the most commonly used dataset that governs computer vision, ImageNet, admitting that the artwork exposed dangerous flaws in how images were categorized. Given how central virality has been to this decade, what I think is particularly significant about ImageNet Roulette is how it launched as an actual app, allowing you to upload an image of yourself, see how the computer was tagging you in often unnerving ways, and share the results. Social media normally can be accused of soft-pedaling digital surveillance by incentivizing self-exposure. In this case, the creators used these same energies to turn the tables, at least in a small way.

Ragnar Kjartansson, The Visitors (2012). Photo: Elísabet Davids. Courtesy of the artist, Luhring Augustine, and i8 Gallery.

I wouldn’t be the first to put Kjartansson’s dreamy, multi-channel, hour-long video at the top of their list of faves. The Icelandic artist calls himself a “neo-Romantic,” and the film, set in the disheveled grandeur of the rooms of Rokeby Farms in New York, features multiple musicians setting up, then jamming together on separate screens, slowly coming together, and then breaking up. It casts a spell that is hard to describe (see a clip here). Seven years after I saw it at Luhring Augustine gallery, I can still sing the hook from The Visitors in my head.

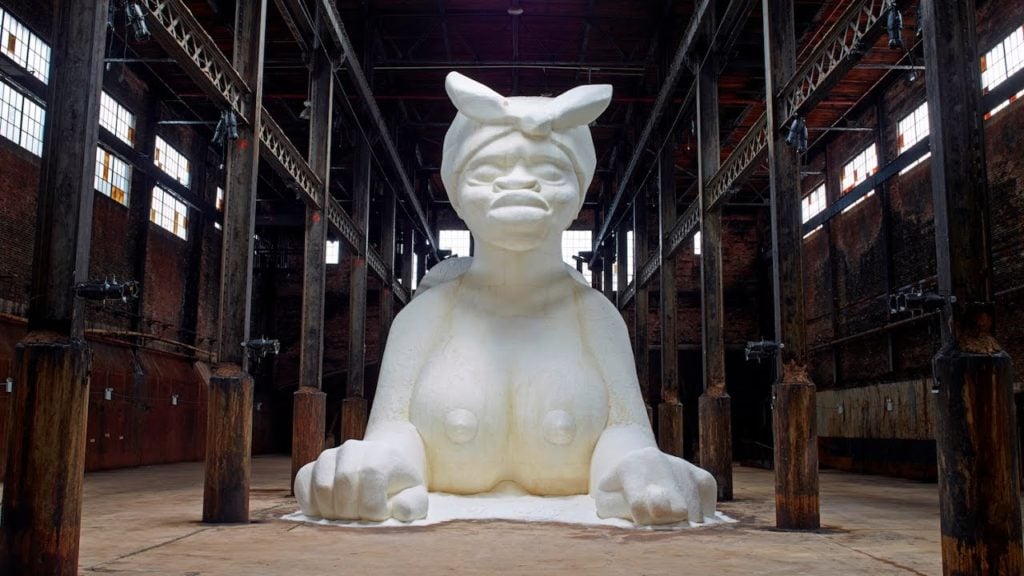

Kara Walker’s A Subtlety… at the Domino Sugar Factory in 2014. Image courtesy Creative Time.

Scale can be a substitute for interest, and working with a symbolically charged material, a substitute for meaning. But Walker’s sphinx, made from some 35 tons of sugar, probably marks a high point for doing something actually meaningful and interesting while working at that kind of scale. It draws you in with a spectacular image in a spectacular site, but its idea is audacious and multifaceted enough that it has entered the culture in a lasting way.

Christian Marclay, The Clock at the Walker Art Center. Image courtesy the artist and Walker Art Center.

A work recognized as a classic almost as soon as it came out (shoot, I called it a “New Classic” for a series in Slate in 2011!), Marclay’s The Clock is an idea so perfect that it feels almost elemental: clips of film from throughout cinema history, each featuring a clock or some reference to time, but organized so that whatever moment the characters are experiencing onscreen lines up with the moment you are in, right in the gallery. It was a tremendous achievement that was rewarded with vast popularity; there are people who showed up and sat through all 24 hours.

It’s worth saying why, though: The Clock takes the fragmented, atomized, atemporal way we have come to consume media, digs into the guts of the mechanism, and rewires it to reconnect with a sense of continuity, actuality, and a collective experience of the present. In that sense, it is a work with an almost healing power. And it is also just wonderfully, innately lovable.

Arthur Jafa, The White Album (2018) at the Venice Biennale 2019. Image: Ben Davis.

Arthur Jafa’s Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death seemed to compress the entire hyper-charged media landscape, where images of racialized ultra-violence circulate alongside affirmation and commodification of black culture, into one seven-minute video collage. This decade’s social media explosion made escaping traumatic images of violence impossible, stimulating both demands for justice and feelings of vulnerability for targeted communities. But processing these images into art without seeming to compromise their reality seemed equally impossible. Jafa’s artwork steered straight into this traumatic paradox, the video’s movement between extremes of horror and celebration capturing a sense of psychic crisis. Arriving at Gavin Brown’s enterprise in New York just at the moment of Trump’s election in 2016, it became a symbol of the anger and grief of that moment. It drew lines.

In this list, I’ve tried to have only one work by a given artist, just to keep this totally arbitrary exercise interesting. I gave myself an exception for Jafa, because it seems to me that Love Is the Message, the Message Is Death makes sense at the top for the reasons I just mentioned—but the artist himself spoke about being suspicious of the over-celebration of his work by a white audience, which makes total sense given that it is about how the celebration of black culture coexists with the reality of oppression (the title of the work literally states this message). The White Album was his response to that problem, this time stitching a found-image portrait of white America: of vigilante violence, of awkward internet rants from people alternatively spouting clueless shit or struggling towards a language of anti-racism, of inane viral goofiness that doesn’t seem so goofy anymore in this context, asking you to sit with what it all means together. The same compression of highs and lows, but with the mirror turned around.

These two works felt unexpected and difficult in the way truly new kinds of art do. Their form, collaging found and viral-media images with appropriated music, was radical but also a vernacular and accessible language. They felt both unusually direct and honest but also meticulous and careful with their material. People will still be processing them in the 2020s.