Opinion

The ‘Quasi-Theological’ Turn in Art Criticism Is a Mirage Leading Us the Wrong Way

"Negative Reviews? Part 2," from a 2-part essay on contemporary art writing.

"Negative Reviews? Part 2," from a 2-part essay on contemporary art writing.

Ben Davis

This is the second part of a two-part essay. Read the first part, here.

Towards the end of Sean Tatol’s “Negative Criticism,” there’s a curious, even startling turn. Unexpectedly, the essay shifts into an almost priestly register:

In the contemporary context, becoming cultured requires a resistance to the prevailing culture, and could ironically be considered countercultural. Nevertheless the pursuit remains necessary, and perhaps even unavoidable, because it is intrinsic to our nature. Cultivation is the growth into a distinct individuality by means of culture, an understanding of oneself and the world that always seeks to more fully encompass this understanding, a knowledge of life, an intelligence. This aspiration reaches toward an absolute, an omniscience that is both desired by and denied to humans: something I might call God if I were religious, but that for our purposes we can call the good. This good is something we can only put ourselves in service to…

Here we get to what interests me most about in this essay. Tatol’s young Manhattan Art Review has people’s attention with its reviews, a real rarity. “Negative Criticism” makes a passionate effort to give this project an intellectual program—and that program sounds like a throwback to something that would have been considered fatally essentialist just a short time ago.

Is this “quasi-theological” language a provocation, like Tatol’s five-star art-rating system? If so, it’s one he takes very seriously, also like that five-star art-rating system—though with more disorienting implications.

As I understand Tatol, the reason he takes this turn is because “absolute” aesthetic standards are being held up as the bulwark against relativism, and aesthetic relativism is being framed as the root cause of the lack of concern with judgement or quality among critics today: “Today the mere suggestion that some things are better than others, particularly in the arts, is met with confusion and hostility.”

Tatol’s idea of artistic standards must exist at a plane above any specific artist’s limited, human self-justification to prevent recourse to statements of the kind “I just like what I like,” which rob us, in his telling, of a reason to aspire to be better, keeping us stuck in the mud of mediocrity, distraction, and half-assed art. An artwork isn’t good because you say it’s good; there is a higher standard that you should aspire to—not “my good” or “your good” but “the good.”

This turn towards a rhetoric of an aesthetic calling appears to be a reaction to the smarmy commercialism and lack of intellectual seriousness within contemporary cultural life—very real and very dispiriting phenomena. It also seems obviously an over-reaction. Since “Negative Criticism” is offered not just as an account of personal preferences but as a method to be emulated, let me explain.

At the outset, a few obvious dilemmas Tatol’s theory raises for me.

First, I’m not sure why you need to negate the idea of “guilty pleasures” to arrive at an appreciation of “serious art.” I appreciate the need to evangelize for difficult art, but I see nothing wrong with “guilty pleasures” on their own. Different forms of culture serve different purposes at different moments of your life. Why should one have to choose between the statements “I like reality TV” or “I like the films of Apichatpong Weerasethakul?”

To me, this either-or mentality reflects the abstract level that the theory is pitched at. (I’ve said before that at least part of what is perceived of as the dumbing down of culture is linked to the fact that people are overworked—an objective factor, not just a subjective failure of will. It’s hard to make the time for “difficult” high culture when you are just really, really tired from work.)

Second, if you concede the fact that taste really is fundamentally subjective and judgements are relative, does it follow logically that you must abandon all ability to argue that “some things are better than others?” I don’t think so. There can simply be multiple standards, multiple ways to grade things.

It is a fact that our society is more pluralistic than it was in the 1930s, when Clement Greenberg was writing “Avant Garde and Kitsch.” There are more active voices and more diverse cultural options, and some portion of postmodern “cultural relativism” was just a pragmatic and salutary acknowledgement of this fact. Aesthetic pluralism on this level is generally a good thing—even if it raises some new difficulties for developing unified standards of judgment.

Third, even if you say (as Tatol says) that the reference to a “quasi-theological” aesthetic standard is just an animating ideal, an aspiration toward transcendent values “desired by and denied to humans” that shakes you out of your self-regard, it seems delusive. The orientation on an “absolute” standard just takes your eyes off the fact that you as a human are seeing art from your own limited, socially conditioned standpoint, with notions of quality shaped by whatever familiar image of “good art” you have.

For me, part of the difficulty, and the fun, of art is how new ways of enjoying things are constantly emerging, how new communities of people invent unexpected new forms of taste that challenge your previous standards. This dynamic is actually represented with Tatol’s choice critical references: Theodor Adorno would have considered rock music absolutely anathema to serious aesthetics, the death of art; Robert Christgau developed his own hyper-refined and rigorous way of judging it.

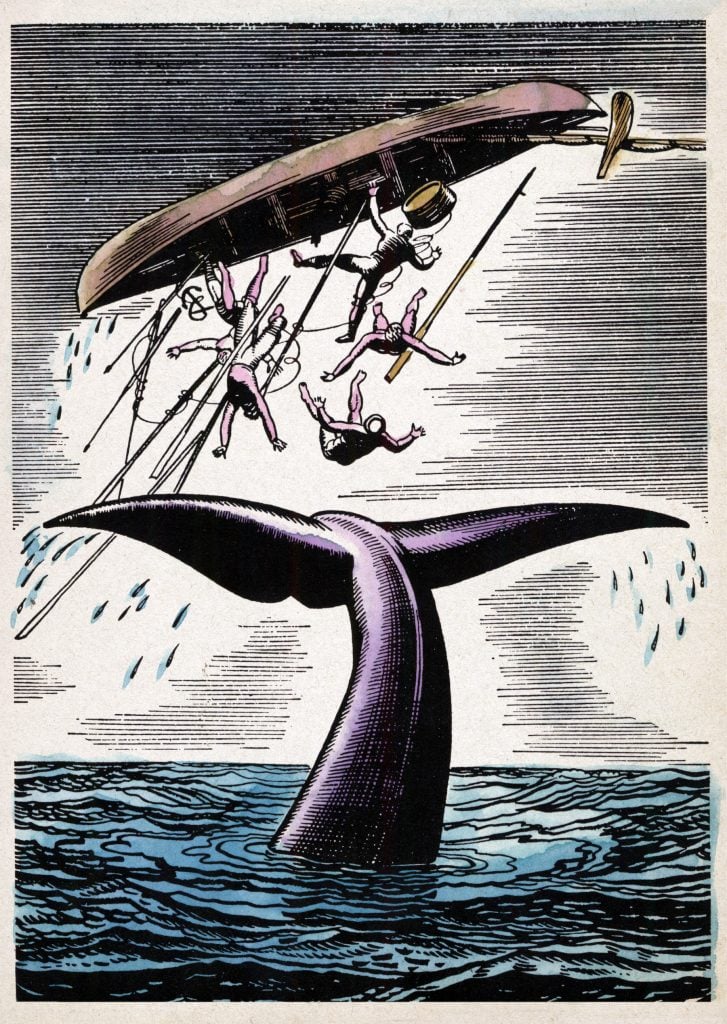

Woodcut illustration from the novel ‘Moby Dick’ by Herman Melville. (Photo by Fototeca Gilardi/Getty Images)

Here’s an example of this unintentionally delusive effect in action. In “Negative Criticism,” Tatol offers the following example to make the case that a generalized “subjective absolutism” (i.e. “I just like what I like”) has turned us away from making grander, more consequential judgments of quality: “A toddler will tend to prefer The Very Hungry Caterpillar to Moby-Dick, subjectively, but a twenty-year-old should be able to discern that the latter is an objectively better work of literature.”

The thing is, this statement is obvious because it is circular. We are comparing a book that defines the canonical sense of what literature is to something that isn’t trying to do the same thing at all. The statement has exactly the same merit as its reverse: “Any twenty-year-old should be able to discern that The Very Hungry Caterpillar is a better book to read to toddlers than Moby-Dick.”

Children’s books are their own genre with their own canon, their own highly developed standards, even their own critics. On the basis of these, Eric Carle’s classic ranks highly, with its fine watercolor illustrations, inventive die-cut format, and charming story.

The question of other people’s subjective values isn’t a distraction from the question of quality. The question of quality requires that you incorporate, at some level, other people. It has to start with the question: “better” for what and for whom?

Tatol writes, “Most contemporary art writing uses interpretation as a way of sidestepping the problem of quality, but interpretations are impossible to take seriously if the art itself is bad.” But again you can easily reverse the formulation: “Debates over quality are impossible to take seriously if the problem of interpretation is sidestepped.” It really does help to know that you are not judging something harshly for not doing something it is not trying to do.

Illustrator Eric Carle during a book signing at San Marino Toy and Booke Shoppe. (Photo by Vince Compagnone/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images)

I generally appreciate Tatol’s mission in “Negative Criticism,” that the point of criticism is role-modeling the “development of intellectual maturity” as it regards art. I think I have a different idea of what “maturity” means. Tatol lays great stress on the need to value difficulty and seriousness, transcending the kinds of easy, undeveloped pleasures one associates with being a kid. He sees strong “negative criticism,” which demands a lot from its object, as a way to vault yourself toward this transcendence.

I view intellectual “maturity” as also about knowing yourself in relationship to others. That is, moving from simply carving out your own sense of identity by defining a personal taste to being curious about why others like what they like and putting yourself in dialogue with those tastes, self-consciously. This is an active negotiation: I don’t want to just passively accept what other people tell me is good; I also don’t want to just arbitrarily impose my own sense of what is good on others.

Peter Schjeldahl offers a nice counterpoint to Tatol on the relationship between judgement and interpretation. Here he is, distilling a career’s worth of experience as a critic into 124 words:

I retain, but suspend, my personal taste to deal with the panoply of the art I see. I have a trick for doing justice to an uncongenial work: “What would I like about this if I liked it?” I may come around; I may not. Failing that, I wonder, What must the people who like this be like? Anthropology.

I assess art by quality and significance. The latter is most decisive for my choice of subjects, because I’m a journalist. There’s art I adore that I won’t write about, because I can’t imagine it mattering enough to general readers. It pertains to my private experience as a person, without which my activity as a critic would wither but which falls outside my critical mandate.

This essay is probably too long, but I hope it’s clear that I am trying to practice what I preach, trying to do justice to Tatol’s argument, interpret its stakes, and define where I part ways with it. Ultimately, though, his “Kritic’s Korner” reviews are entertaining, enliven the scene, and if I or anyone else disagree with this or that judgement, at least we are talking about gallery shows.

What makes all this a larger discussion, however, is that Tatol’s theory of “Negative Criticism” is articulating a frustration that reflects something bigger, which has an ambiguous, not-yet-settled significance. “The critical tide is turning, once again,” Anastasia Berg writes in the intro to the same issue of The Point that “Negative Criticism” hails from. There is now a lot of talk from critics—”and not just the old, curmudgeonly ones,” Berg says—about “standards” and “quality” and “beauty” and so on.

In part, I think this emphasis comes from a sense, which Tatol articulates directly and well, that hyper-consumerist media has weaponized the idea of “guilty pleasures” to justify stuffing our faces with really debased, shoddy aesthetic product, and that on many levels—film, music, and literature, as well as art—the cultural ecosystem feels like it is approaching a point of serious entropy. In part, it is a generational reaction to the everyone-gets-a-trophy pedagogy that middle-class millennials were raised with, as an emerging cohort is faced with narrowing, cutthroat, inaccessible avenues of social advance. In part, there is a backlash against the fact that a lot of canonical works of art that have been deeply meaningful to large numbers of people have been the subject of confusing and reductive critique in the recent period in the name of social justice, so that by now a critical mass among the smart set seems to view the term “social justice” itself as a synonym for anti-intellectualism. (These are our old friends “greed,” “indifference,” and “literal-minded sloganeering,” once again.)

The danger is that all this accumulated frustration can be channeled in a lot of different directions, and various sorts of ideological entrepreneurs are looking to capitalize on it.

In “Negative Criticism,” Tatol writes the following:

The process of learning to discern what separates the truly good from the seemingly good, and the failed attempts at the good from the irredeemably bad, does not follow rules. It cannot be learned like a scientific formula. In a society that has seen a universal decline of the cultural institutions that should exist to edify it, many will not even know that it is a process, or that there is any point in subjecting oneself to it. In this context it becomes doubly important, for the sake of culture as well as for one’s own good, to judge the differences between good and bad, the real, authentic, and profound versus the shallow, the crassly commercial and the uninspired.

This sounds similar to Jordan Peterson, the wildly popular, oddball-reactionary, neo-Jungian philosopher, talking about the evils done by postmodernists who bring a “hatred of quality and qualitative distinctions” to the arts:

The role of artists in a healthy culture is to bring to public awareness elements of being that have not yet entered public consciousness… Artists move us forward into the unknown… With young people you want to say… Look, there are true qualitative distinctions between things… There are heights that you can ascend to that are genuinely high, which means they are above where you are now. But the fact that there are those things to pursue gives your life deep meaning and significance and gives your struggle nobility and validity. And the postmodernists—neo-Marxists, as far as I am concerned—are absolute enemies of qualitative distinctions. So what they do is destroy everyone’s ambition.

Now, Tatol’s key philosophical references include Marcuse and Adorno, neo-Marxists both (and definitely not “absolute enemies of qualitative distinctions”). I’m almost certain he wouldn’t agree with Peterson’s larger conservative political worldview. And, understand, I am not comparing Sean Tatol’s theory of criticism to Jordan Peterson’s guru act as a dunk. Personally, I find unobjectionable the idea that a connection to art can be life-changing, is something to aspire to, and involves cultivating an understanding of how to make qualitative distinctions.

Jordan Peterson addresses students at The Cambridge Union on November 2, 2018. (Photo by Chris Williamson/Getty Images)

But if the vision for culture being offered is different from cultural conservatism in either its old-school or new-model forms, where a call to reassert aesthetic hierarchies is read together with a call to reassert social hierarchies, there’s good reason to be clear about how.

Peterson and others are babbling on about how “Western culture” and “Judeo-Christian values” are under assault by demonic feminists and perfidious cultural Marxists. When Tatol writes “becoming cultured requires a resistance to the prevailing culture, and could ironically be considered countercultural,” obviously, “becoming cultured” is a very charged term at a time of Category 5 “culture war” politics—yet there’s only a cursory attempt in “Negative Criticism” to set what Tatol is saying off from the surrounding climate of “anti-woke” bluster. (I too think Ulysses and Thomas Aquinas are great—but it does not help that all the examples of cultural “maturity” Tatol offers are traditional Western Canon fare.)

The simplest and philosophically cleanest way to make this differentiation is just to incorporate the reality of aesthetic pluralism as a positive force into the theory—to say that it is not always a name for intellectual laziness but can also be a name for intellectual curiosity, that it is not a barrier to having standards but their desirable starting point. And I do wonder whether on some level the “quasi-theological” turn, the call to root art criticism in an orientation toward “absolute” values that exist beyond all context, doesn’t serve as a way to avoid reckoning with the more unfortunate resonances of that call in our own actual fractious contemporary context.