Archaeology & History

Ancient Scroll’s Secrets Unlocked Using State-of-the-Art Technology

With cutting-edge tomography, researchers were able to "digital unroll" the brittle scroll.

In 2018, in the north of the Alps, archaeologists unearthed an ancient silver amulet, which they later recognized as the oldest known Christian artifact to be found in the region. What they couldn’t crack, however, was a scroll tucked into the small relic—one that could not be unrolled for fear of crumbling the brittle paper. Now, six years on, researchers in the German city of Frankfurt have gotten an unprecedented glimpse into the mysterious artifact, thanks to state-of-the-art technology.

Measuring a mere 1.3 inches, the amulet itself was found on a burial ground in the Roman city of Nida, now known as Frankfurt, and is thought to date back to between 230 and 270 C.E. The scroll it contained was already evident during excavation, but because it had spent centuries rolled up, any attempts to unfurl it would cause it to fall apart, researchers believed. Microscopic analyses and X-rays, too, proved unable to offer further insight into the scroll’s contents.

Archaeologists excavating the amulet. Photo: Michael Obst, courtesy of Denkmalamt Stadt Frankfurt am Main.

An answer ultimately arrived in the form of cutting-edge computer tomography developed by the Leibniz Center for Archaeology (LEIZA) in Mainz, which allowed researchers to “digitally unroll” the brittle silver foil earlier this year—not unlike the type of technology used in the efforts to decipher the Herculaneum scrolls. What it yielded was a high-resolution 3D model of the scroll’s 18-line-long inscription.

The silver amulet containing a scroll. Photo: Archaeological Museum Frankfurt.

The inscription is written in Latin, an unusual choice for Christian amulets of the time. It contains invocations to Jesus Christ and Saint Titus, a Greek missionary who lived during the 2nd century C.E. More typical of early Christian amulets, it celebrates the power of Heavenly Father while referencing passages from the Bible. Unlike other early Christian artifacts, however, the amulet bears no mention of the Judaic and pagan traditions that influenced the still-evolving religion.

“[In the name?] of Saint Titus / Holy, holy, holy! / In the name of Jesus Christ, Son of God! / The Lord of the world / resists with [strengths?] all attacks(?)/setbacks(?) / The God(?) grants / entry to well-being,” the inscription reads in part.

“Sometimes it took weeks, even months before I had the next idea,” Markus Scholz of Frankfurt’s Goethe University, who led the research project, said in a statement. “I called in experts from the history of theology, among others, and we approached the text together, piece by piece, and finally deciphered it.”

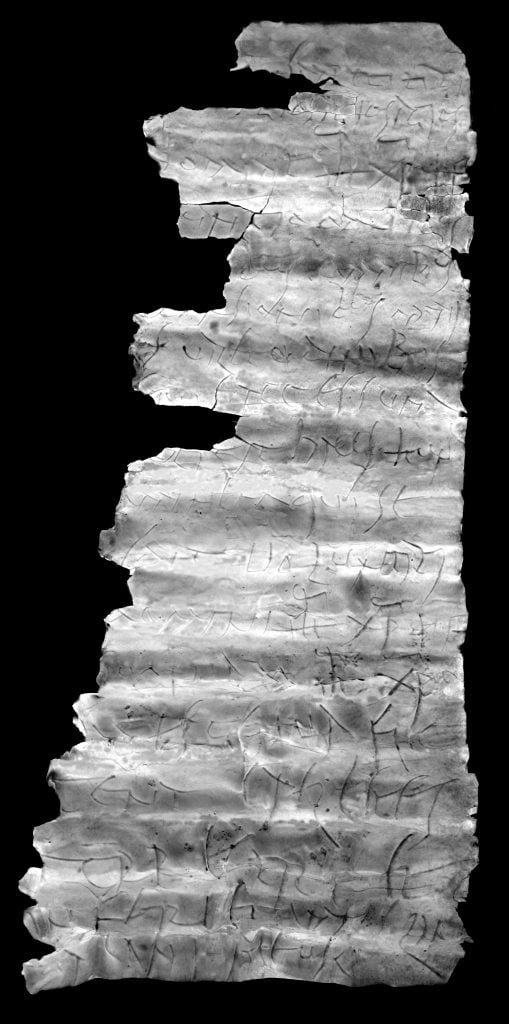

Photograph of the inscribed text, unrolled. Photo: LEIZA.

“What is unusual,” he continues, “is that the inscription is written entirely in Latin. Such inscriptions in amulets were usually written in Greek or Hebrew.” The quality of the inscription, not to mention its minuscule size, suggests it was made by a trained scribe or craftsman.

The amulet provides direct evidence of Christian communities living in Upper Germania and Gaul, a region of modern-day France, during the late 2nd and 3rd centuries C.E. Most other evidence dates from the early 4th century C.E., after emperor Constantine’s Edict of Milan turned Christianity from a persecuted cult into an officially recognized, tolerated faith.

The find is not only significant to research into early Christianity but also to the cultural and historical heritage of the city of Frankfurt.

“This discovery,” the city’s mayor, Mike Josef, remarked in the wake of the inscription’s deciphering, “is a scientific sensation. It will force us to turn back the history of Christianity in Frankfurt and far beyond by around 50 to 100 years. The first Christian find north of the Alps comes from our city: we can be proud of that, especially now, so close to Christmas. Those involved have done a great job.”

The inscription’s deciphering is sure to resurrect debate among scholars of early Christianity and Roman history, two deeply interconnected subjects with muddled but culturally relevant origins.