Art History

Here Are Three Things You Might Not Know About Hokusai’s ‘The Great Wave’

The iconic Japanese print has inspired everything from Impressionism to Emojis.

The iconic Japanese print has inspired everything from Impressionism to Emojis.

Annikka Olsen

Katsushika Hokusai’s Japanese woodblock print colloquially known as “The Great Wave” stands as one of the most famous and widely reproduced images in the world. The famed composition crops up on everything from mugs and notebooks, to scarves and umbrellas, and even appears on the emoji keyboard.

The stylised rendition of “The Great Wave” first appeared on the emoji keyboard in 2015

Created roughly between 1830 and 1832 during the Japanese Edo period, this print depicts three boats encountering a rogue wave of gigantic proportions, with Mount Fuji in the distant background. The work’s official title is Kanagawa oki nami ura, or Under the Wave off Kanagawa, and it is the first print of the series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji”. It falls within the style and tradition of ukiyo-e, a genre of Japanese decorative art comprised of woodblock prints and paintings that frequently depict everyday people (often of lower social strata, like actors and courtesans) as well as landscapes, flora, and fauna.

Perspectives that float somewhere above the subject matter, flat planes of color, and precise and clear rendering are all common trademarks of the genre and remain identifiable as a distinctly historic Japanese aesthetic.

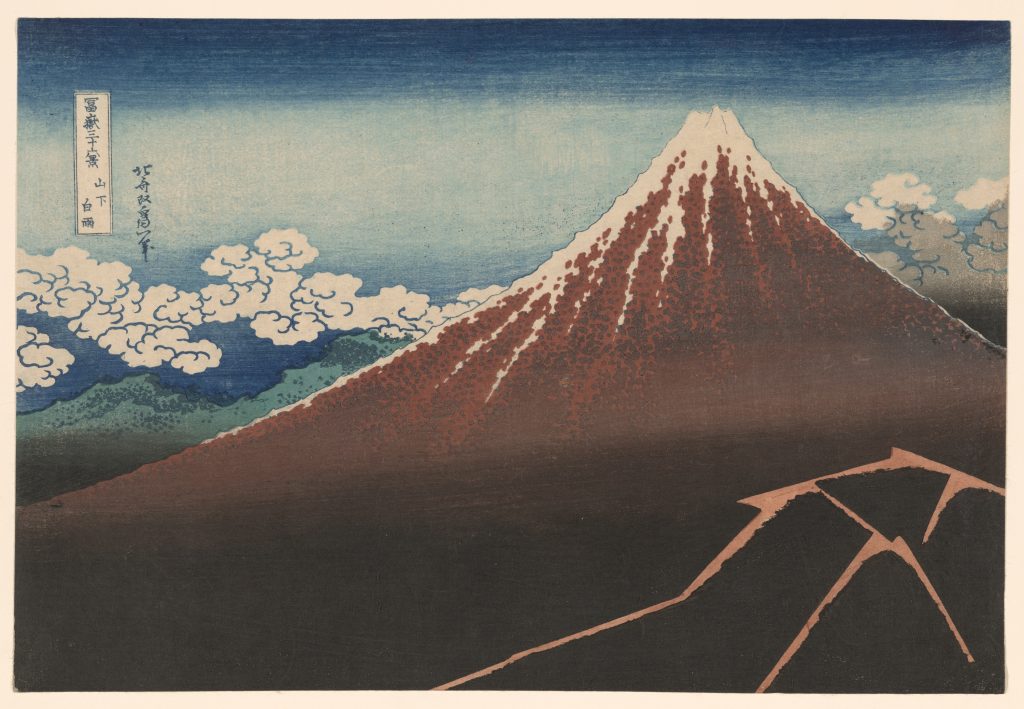

Katsushika Hokusai, Shower Below the Summit (Sanka hakuu) from the series “Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji (Fugaku sanjurokkei)” (ca. 1830–33). Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

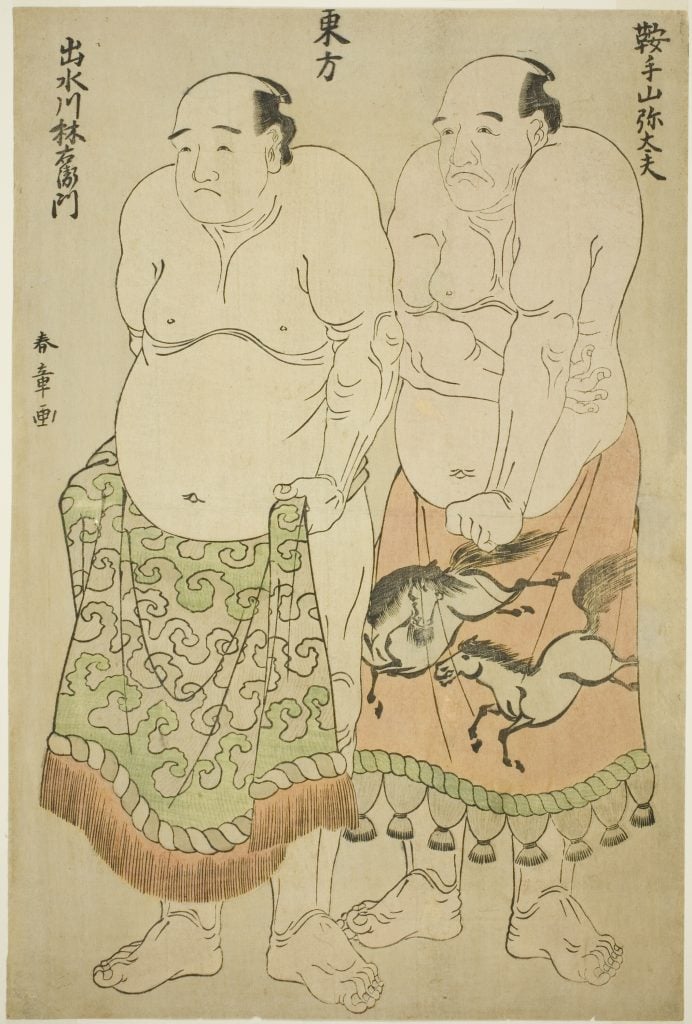

Hokusai was born in 1760 to a family of artisans and began painting—by some accounts—as early as the age of six. He apprenticed with a woodcarver at the age of 14, and at 18 he joined the studio of Katsukawa Shunshō, an artist who worked in the ukiyo-e style and focused on images of actors, courtesans and other common figures in Japan’s cities.

Hokusai’s first series of prints, depicting Kabuki actors, was published in 1779. He continued to work conventionally through the early 1790s, at which point he began experimenting with style and composition. This included adopting European art practices that he would have encountered in French and Dutch copper engravings. They filtered into the country despite a strict policy of national isolation, which finally ended in the mid-1850s.

Katsukawa Shunsho, Sumo Wrestlers of the Eastern Group: Kurateyama Yadayû and Izumigawa Rin’emon (1775–1785). Collection of the Art Institute of Chicago.

Hokusai, surname Katsushika, is just one of the names the artist was known by. He frequently adopted a new moniker as part of his life and practice, going by at least 30 iterations over the course of his lifetime. Although using different names was not atypical for Japanese artists of the period, this took it to another level. In retrospect, these regular changes have aided scholars and historians in codifying periods in the artist’s life and career. He began using “Hokusai” around the turn of the 19th century, which would remain his most widely known title.

Even with a career that spanned some 70-plus years, Hokusai’s practice was nothing short of prodigious. Estimates put his oeuvre at more than 30,000 works, including paintings, sketches and prints. Though insight into the history of Japanese art-making and the trajectory of Hokusai’s career can be found in any number of his works, Under the Wave off Kanagawa has continued to capture the eye and attention of the world, nearly two centuries after its creation.

Here are three lesser-known facts about the iconic print.

The pigment Prussian blue, or Berliner Blau.

One of the most captivating elements of Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa is the vivid and varied use of the color blue. Though today we might not think of these hues as exotic or remarkable in and of themselves, at the time the development of a stable blue was at the forefront of scientific discovery.

Around 1705, Swiss pigment maker Johann Jacob Diesbach set about making a red pigment, and accidentally used a compound containing a toxic oil created by failed German alchemist Johann Konrad Dippel, with whom he shared a lab to save money. The unintended result was a vibrant and stable (meaning not prone to fading or other deterioration) blue, later dubbed Prussian blue. Previously, similar shades were only achievable through crushing up the very expensive gemstone Lapis Lazuli, which was extracted from the mountains of Afghanistan.

Swatch of Prussian blue oil paint.

The new pigment led to a “blue fever” that swept Europe, with the color appearing in everything from clothes, to paintings, to wallpaper. Even tea leaves were dyed to follow the fashion, an act that was, as one might imagine, extremely toxic. It wasn’t until the early 1800s when a Chinese entrepreneur developed a new version of the recipe, that the hue arrived in Asian markets. Although at that point Japan maintained harsh import regulations, the blue pigment soon appeared in the printmaking scene of Osaka.

The introduction of the blue had similar seismic repercussions as those seen in Europe, with artists adopting the color widely—including Hokusai. The Japanese referred to it as “Bero”, a derivation of “Berlyns blaauw”, Dutch for “Berlin Blue”, (the Netherlands had special dispensation to trade via a port in Nagasaki). The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Scientific Research team conducted a spectroscopic analysis of the museum’s edition of Under the Wave off Kanagawa and found that rather than wholly adopting the then-new blue hue, printers meticulously layered it with a more traditional pigment made from the indigo plant, which was steelier in shade.

The conclusion was that the first pass of the print included a mixture of Prussian blue and indigo, with the second laying down pure Prussian blue, to produce a more nuanced effect. The result is what we see today: a dynamic undulation of blue hues within the water’s surface, conveying a powerful sense of movement.

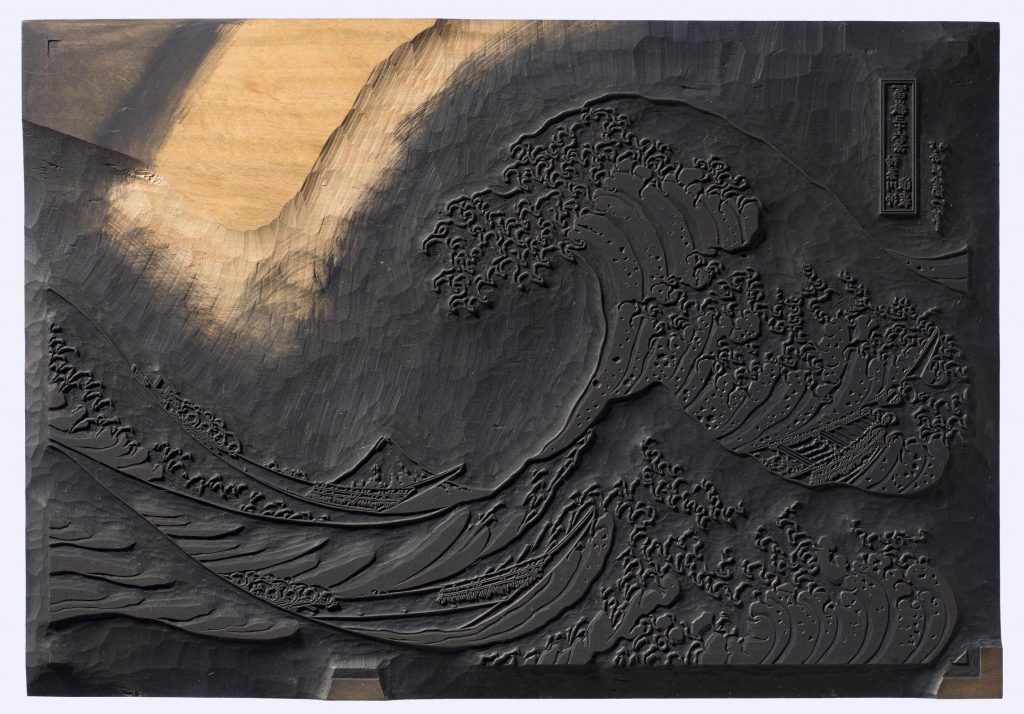

Printing-block (woodblock). Outline block (omohan) cut for a modern fascimile (2017) reproduction of Under the Wave off Kanagawa by Katsushika Hokusai. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

It is thought that 1,000 editions of Under the Wave off Kanagawa were originally printed, and upwards of 8,000 were eventually made in total. However, these prints—and ukiyo-e overall—were not considered “fine art” in Japan. They were cheaply made and sold, and thought of more as commercial design. Because of this, many of the prints were initially not very well cared for, with most becoming damaged or simply thrown away. Of the thousands originally produced, it is estimated that the number still extant is only in the hundreds. Rarifying the prints even more is the fact that in the woodblocks were customarily used until failure, meaning that later editions of the print show signs of wear and damage.

The non-art sentiment ultimately didn’t change until Japan opened several of its ports to other countries in 1859, after which a wave (pun intended) of ukiyo-e and other Japanese art forms flowed through the rest of the world. Fascinated by these works, they became a popular souvenir and export, leading to a renewed interest in the industry. Despite being considered a crude art form, the aesthetic of these woodblock prints was considered by the West as quintessential Japanese art. It is a notion that still persists today.

The obsession with ukiyo-e and specifically Hokusai’s Under the Wave of Kanagawa has remained strong. Earlier this year, an excellent iteration of the print sold at auction with Christie’s New York $2.76 million—exponentially more than the original price, which equated to a humble bowl of noodles.

Vincent van Gogh, The Starry Night (1889). Collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

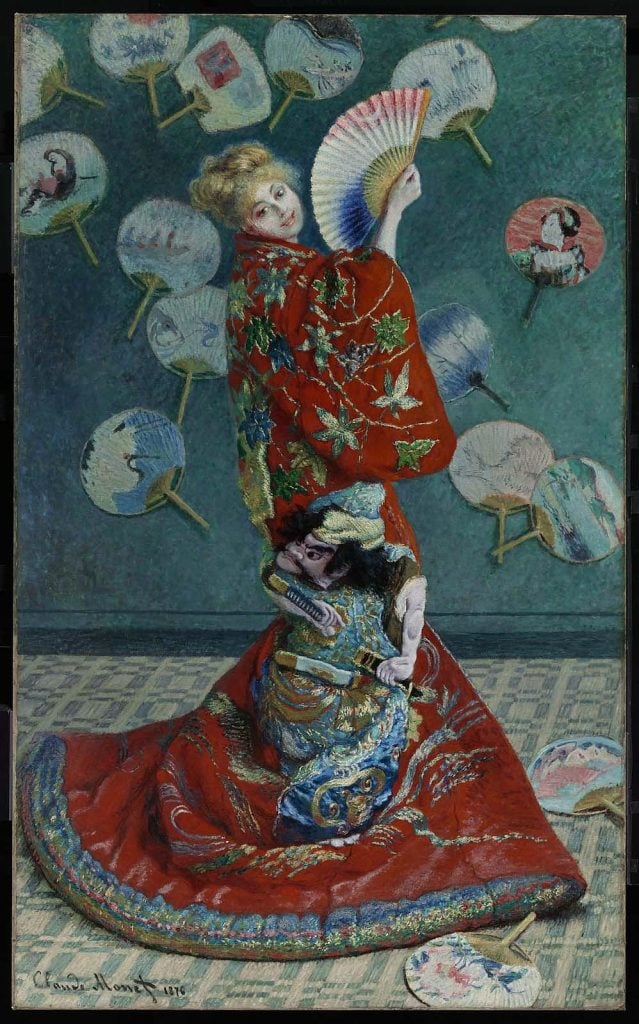

The influx of Japanese art, craft, and other cultural materials into Europe in the 19th century was profoundly influential, leading to the rise of what has been termed “La Japonaise” or “Japonisme,” a French term referring to the frenzy for all things Japanese in the western world. The effect of this craze is widely seen in the work of the Impressionists, with artists such as Claude Monet including traditional Japanese garb and fans in a painting of his wife, titled Camille Monet in Japanese Costume (1876). Following his move to Giverny in 1883, he added a Japanese footbridge to his garden, which became a fixture in many of his paintings.

Taking inspiration from woodcuts specifically, Mary Cassatt created a series of etchings that use similar fields of color, line work, and perspective, as can be seen in her Maternal Caress (1890–91).

Claude Monet, La Japonaise (Camille Monet in Japanese Costume) (1876). Collection of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

Recent considerations of Hokusai’s Under the Wave off Kanagawa and its influence have connected the image to another artwork that vies for the position of most famous worldwide: Vincent van Gogh’s The Starry Night (1889). It has been long known that van Gogh was a collector and admirer of Japanese prints, but in 2018 Martin Bailey—a Van Gogh specialist and the Art Newspaper correspondent—published a piece connecting the two iconic works.

Bailey cites letters written by the artist to his brother Theo, (“[Hokusai’s] waves are claws, the boat is caught in them, you can feel it”) and observes parallels in the rich use of the color blue and swirling compositions. He suggests that Van Gogh’s encounter with the ukiyo-e artist and his work was inspirational and possibly significant to the completion of The Starry Night.

More Trending Stories:

Conservators Find a ‘Monstrous Figure’ Hidden in an 18th-Century Joshua Reynolds Painting

A First-Class Dinner Menu Salvaged From the Titanic Makes Waves at Auction

The Louvre Seeks Donations to Stop an American Museum From Acquiring a French Masterpiece

Meet the Woman Behind ‘Weird Medieval Guys,’ the Internet Hit Mining Odd Art From the Middle Ages

A Golden Rothko Shines at Christie’s as Passion for Abstract Expressionism Endures

Agnes Martin Is the Quiet Star of the New York Sales. Here’s Why $18.7 Million Is Still a Bargain

Mega Collector Joseph Lau Shoots Down Rumors That His Wife Lost Him Billions in Bad Investments