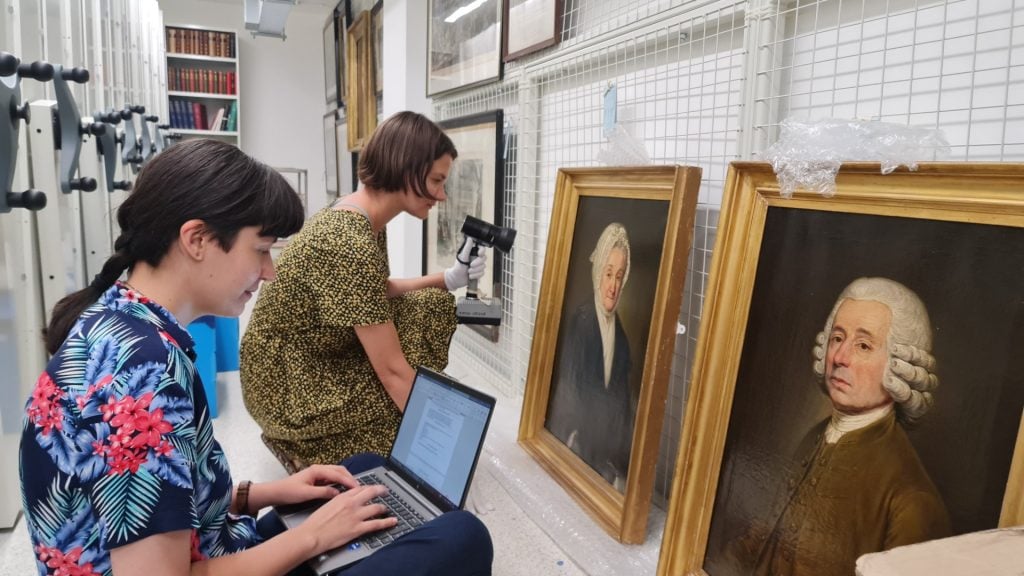

Two painting conservators from Ukraine who are currently living in the U.K. as refugees have been given the opportunity to practice their professions at the Huguenot Museum in Kent, England. Ahneta Shashkova and Valeriia Kravchenko both trained as conservators at the Kyiv Academy of Art and Architecture, but were forced to leave Ukraine after Russia’s invasion in February 2022.

The pair conserved the 18th-century portraits of goldsmith John Jacob, who was himself a Huguenot refugee, and of his wife Anne Courtauld, the daughter of another Huguenot goldsmith who had been a refugee. The paintings have gone on public view at the museum this week in commemoration of Refugee Week.

Starting in August 2022, the pair worked under the guidance of the Ukrainian-born conservator Katya Belaia-Selzer, who has been living and working in the U.K. for many years at her studio in Buckinghamshire. She set up a society of Ukrainian conservators in 2014. Since Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, she has arranged for 15 of her colleagues to flee the war-torn country and settle in England.

“The Huguenot Museum gave an incredible opportunity to two Ukrainian refugees, professional paintings conservators, to continue practicing their craft and find dignity and meaning in spite of the appalling events currently unfolding in their homeland,” said Belaia-Selzer in a press statement.

The portrait of Jacob was on a very fragile canvas with the paint beginning to flake. Both paintings had grown dull over the years thanks to dirt and old darkened varnish. In some cases, the original pigments used were highly sensitive and required a careful hand in cleaning.

Unknown artist, Anne Courtauld, Mrs Jean Jacob (c.1787-93). Photo: © Huguenot Museum, Rochester.

“One could finally see all the details in the dress—the buttons, the lace, the quality of the fabric—as well as all the little artistic changes in composition, which is extremely exciting,” Belaia said of the cleaning process. “It is like seeing the artist at work.”

The Huguenot Museum has particular resonance for the history of refugees. In 1685, the King of France ruled that Protestants living in France would be barred from leaving and forced to convert to Roman Catholicism. Over 200,000 managed to escape and around 50,000 ended up settling in the U.K., introducing the term “refugee” to the English language.

The project took place thanks to funding from the British-based Idlewild Trust and Leche Trust with further contributions from the Faith Project, Bishop Auckland and a descendant of John Jacob.

The museum is also marking Refugee Week by exhibiting Our Family Quilt, a textile stitched in collaboration between Ukrainian women living locally and their British host families. Each square in the quilt bears the name of a Ukrainian town that the refugees are from or the place where they are currently living.

More Trending Stories:

A Bejeweled Prayer Book in a Cambridge Library Has Been Identified as Belonging to Thomas Cromwell, Henry VIII’s Chief Minister

The Brooklyn Museum’s Much-Criticized ‘It’s Pablo-matic’ Show Is Actually Weirdly at War With Itself Over Hannah Gadsby’s Art History

Rubens Painting Lost For 300 Years and Misidentified When Last Sold at Auction Will Star At Upcoming Sotheby’s Sale in London

In Her Cinema-Inspired Paintings, Eunnam Hong Captures the Uneasiness of the Alternative Identities We All Put On

London’s National Portrait Gallery Responds to Rumors That Kate Middleton Pressured It to Remove a Portrait of Princes William and Harry

French Archaeologists Decry the Loss of 7,000-Year-Old Standing Stones on a Site That Was ‘Destroyed’ to Make Way for a DIY Store

Excavations at an Ancient Roman Fort in Spain Have Turned Up a 2,000-Year-Old Rock Carved With a Human Face and Phallus