Art Criticism

The 2022 Venice Biennale Is an Artistically Outstanding, Philosophically Troubling Hymn to Post-Humanism

"Post-humanism" is the master key to the big show. But what does it mean?

"Post-humanism" is the master key to the big show. But what does it mean?

Ben Davis

The last edition of the Venice Biennale, the Ralph Rugoff-curated “May You Live in Interesting Times” from 2019, was a grimly elegiac show, full of portents of a civilization falling apart. I called it the “we’re-all-gonna-die-ennial.” Cecilia Alemani, the curator of this year’s 59th edition of the all-important international art show, was named in early 2020, just as the pandemic was set to hit Italy.

Since, there have only been more portents of civilizational collapse: the horrors of COVID, the war in Ukraine, the now terrifyingly close climate change point-of-no-return. Yet the 2022 Biennale, with the poetic title “The Milk of Dreams,” feels lighter, not darker—full of myth, color, and literal magic. As Alemani says in the interview that opens the mammoth, close-to-800-page catalogue of the show, “despite the climate that forged it, this is an optimistic exhibition, which celebrates art and its capacity to create alternative cosmologies and new conditions of existence.”

The Biennale’s opening gambit in the Giardini section of the show is actually positively whimsical. Orange telescopes have been installed around the lawn, so you can peer up at the roof of the Central Pavilion, where Cosima von Bonin has placed a row of capering cartoon sea creature sculptures. It’s as if the show is asking its viewer to look up from our present situation, into imagination.

Telescope pointed at the Central Pavilion as part of a work by Cosima von Bonin for “The Milk of Dreams.” Photo by Ben Davis.

There’s something to think about in the contrast between 2019 and 2022 Biennales. I think it is more than just a “return of beauty Biennale” after a “political Biennale” (an oscillation that has marked this event traditionally).

But first, some assessment of Alemani’s show on its own: It’s very good.

For a number of reasons, “The Milk of Dreams” feels destined to be remembered as a landmark, to be studied and debated. It’s full of surprises but is also unusually holistic and coherent throughout the Biennale’s vast spaces. It feels like a synthesis of a lot of recent conversations in art: the interest in the spiritual and the mythic; the recovery of historical women artists (a vast majority of the artists in the show are women); the attention to the legacy and continued relevance of alternative Surrealisms; the focus on undoing colonial structures of thought via art. But at the same time, “The Milk of Dreams” feels like a singular vision of Alemani, judiciously chosen, full of quirks and kinks.

There’s a focus on embodied experience, and a satisfying rhythm to the show. It is full of moments of thoughtful call-and-response between works.

Simone Leigh’s Brick House greets visitors in the opening gallery. Photo by Ben Davis.

The Arsenale begins with Simone Leigh’s giant bronze bust Brick House (2019), from her “Anatomy of Architecture” series of woman-architecture hybrids. Brick House shares its chamber with the haunted, smoky black-and-white images of the late Cuban printmaker Belkis Ayón, which draw on the lore of a Cuban secret society. Leigh’s Black female figure has no eyes, the artist’s symbol of centered interiority; Ayón’s works often dwell on the figure of a mythical princess, Sikán, who is conventionally shown as having only eyes.

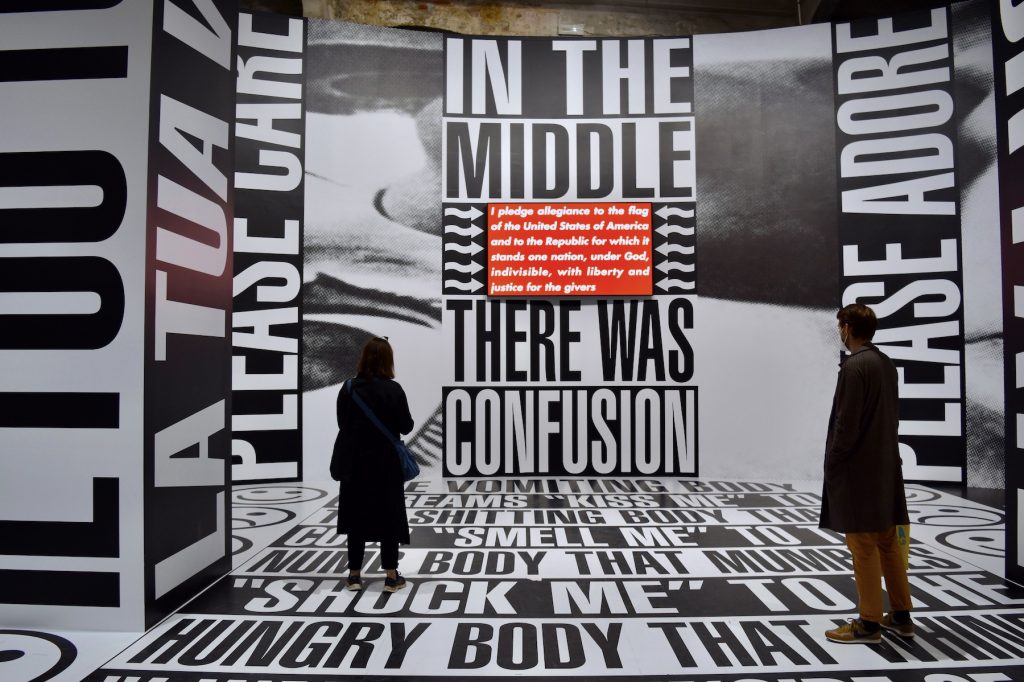

All the way at the other end of the long passageway of the Arsenale, the show comes to a first climax in another soaring chamber that feels like a deliberate contrast to the awe and reverence of that first room: Barbara Kruger’s Untitled (Beginning/Middle/End) (2022), full of monumentalized, ominous texts in her signature style. Here, we are in the anxious media battlefield of the present, full of free-floating unease.

Barbara Kruger, Untitled (Beginning/Middle/End) (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

Turning right, then, down the final leg of the Arsenale space, you arrive at the actual conclusion of the building’s display: Precious Okoyomon’s installation To See the Earth Before the End of the World (2022), a rolling garden, full of bushy human forms, a rumbling abstract soundtrack, a meandering path, and an actual brook. It could be about bringing you into alignment with the earth. Or it could be prefiguring a depopulated world (it’s filled with kudzu and sugarcane meant to overtake it in the course of its run).

Okoyomon’s room feels like it holds the spirit of the mysteries of the Leigh/Ayón room and the anxieties of the Kruger room together, in suspension. You pass from a sense of rooting in tradition and the past, to confronting a charged present, to a future that could go either way.

Katharina Fritsch, Elephant (1989). Photo by Ben Davis.

Over at the Central Pavilion space, things feel a bit less clear-cut as a narrative (but then the Arsenale is easier to read, as a linear space).

It begins with a giddy showstopper, Katharina Fritsch’s life-size green elephant on a pedestal. Exploring the show, you eventually ascend to a gallery featuring the only performance in “The Milk of Dreams,” Romanian artist Alexandra Pirici’s Encyclopedia of Relations (2022–ongoing), where a crew of performers loll, pose, embrace, sing, and do coordinated dance routines, combining and recombining in the space. It feels like walking into someone else’s dream.

So you go from the spectacle of Fritsch’s hyper-real simulation at one end, to the spectacle of “live sculpture” at the other.

Performers in Alexandra Pirici’s Encyclopedia of Relations (2022–ongoing). Photo by Ben Davis.

There are some galleries where I feel a little lost at the Central Pavilion, spatially and conceptually. But there are many more spectacular set piece moments: the gallery of Cecilia Vicuña’s imaginative, and quite funny, paintings; a dark-painted room dedicated to the hardcore fairytales of Paula Rego; Agnes Denes’s majestically intelligent work, displayed under glass, laying out the progression of tools that have shaped human consciousness since the Stone Age in a fantastic hieroglyphic chart; the display dedicated to the Danish-born Louis Marcussen, who adopted the gender-neutral name of Overtaci and dreamed up a parallel universe of cat-like female creatures while living in a psychiatric hospital.

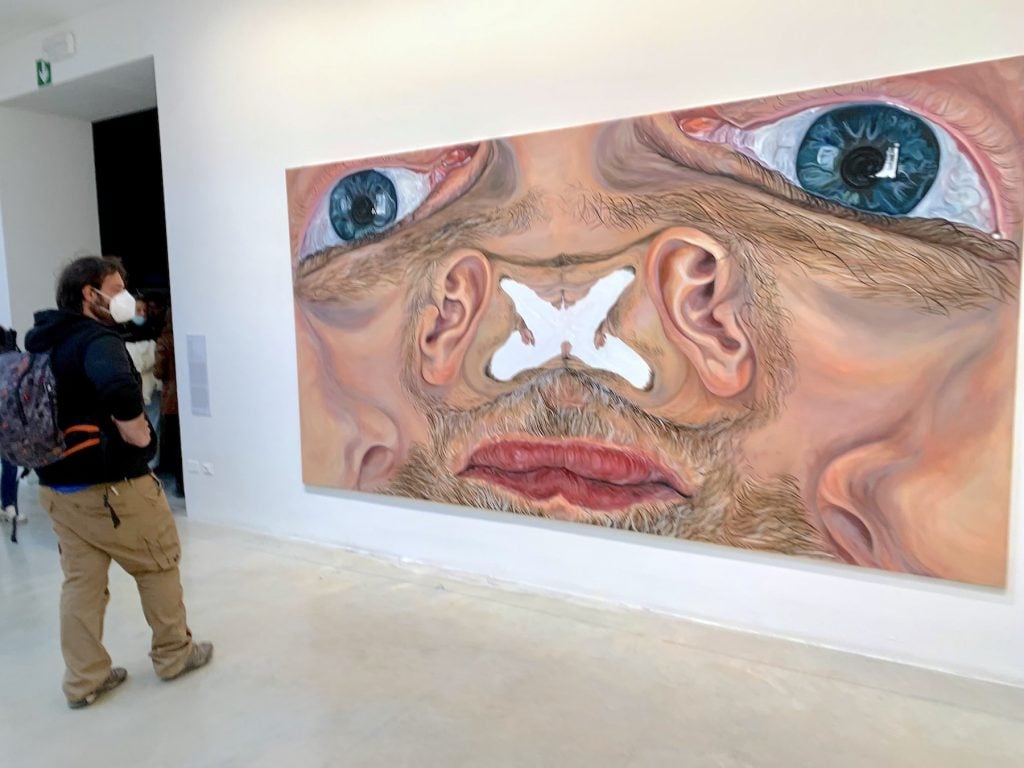

Neo-Surrealist painting is everywhere throughout the show, in lovely and engaging forms. Louise Bonnet’s Pisser Triptych is a gas; Jana Euler’s strange trick painting of an unravelling face is as odd as any painting I’ve seen recently.

Jana Euler, Venice Void (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

There’s also quite a bit of sculpture with an edgy mythological presence. Ali Cherri’s earthen beasts have an elemental power, as do Hannah Levy’s menacing, spidery constructions. Myths and monsters recur again and again.

As usual for big biennials, there’s a formidable amount of video. But it’s judiciously deployed and ultimately manageable. Of these, Marianna Simnett’s The Severed Tail (2022) is certainly the most talked about, with its hilariously grotesque S&M dog show full of humans dressed as animals, and its climactic encounter with a vomiting, perverted demon king.

Marianna Simnett, The Severed Tail (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

In a show full of references to myths past, Simnett’s opus feels closest to presenting something like a brand-new myth. I think I will have nightmares about it.

The most distinctive curatorial flourish of “The Milk of Dreams” is the inclusion of five historically focused all-female capsule shows, two in the Arsenale and three in the Central Pavilion.

Each of these is marked off from the rest by a special color scheme and decor. But even apart from these installation flourishes—ocher carpet and low lights in the capsule called “The Witch’s Cradle,” or cerulean walls and giant black-and-white photos showing the included artists performing in “The Seduction of the Cyborg”—you would sense that Alemani’s Biennale has abruptly shifted gear in these rooms.

A display in “The Witch’s Cradle” gallery in “The Milk of Dreams,” showing Alice Rahon, Untitled (n.d.) and The Juggler (1946). Photo by Ben Davis.

In contrast to the lush clarity of the rest of the Biennale’s curation, here you are suddenly plunged into a lot of historical material displayed under glass or in dense clusters. Reading becomes essential. Different genres and modes of making rub shoulders, including things wholly outside what you traditionally think of as art.

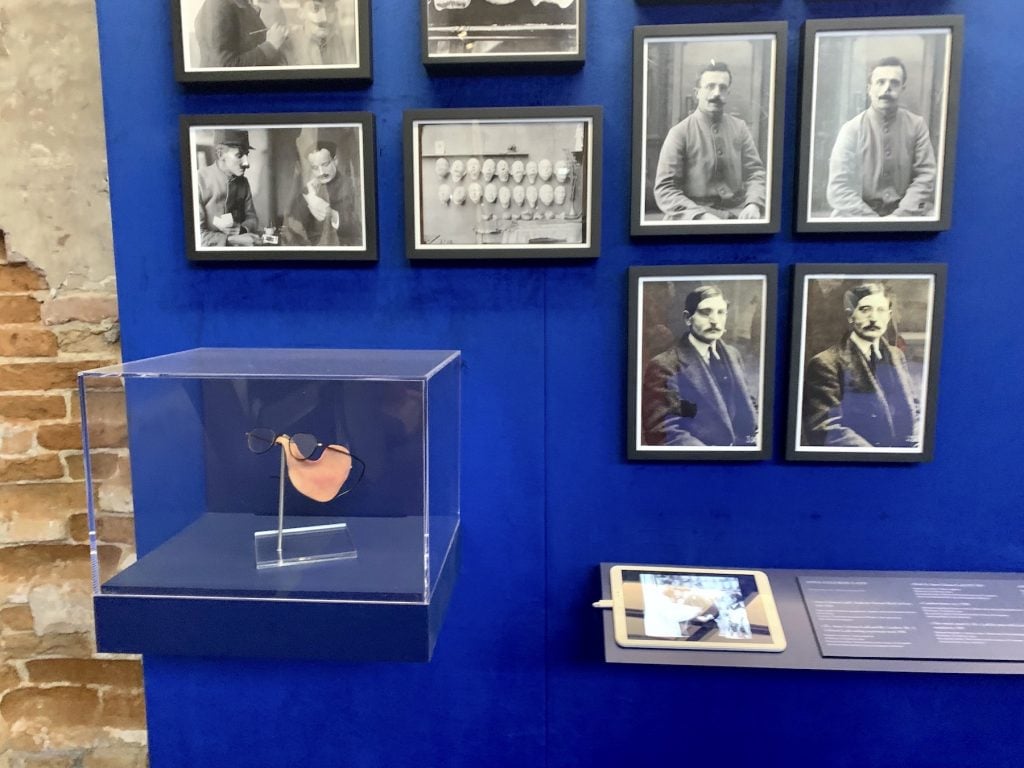

In one mini-show dedicated to the metaphor of the container or vessel, there are non-functional ceramic vase-sculptures (Hawaiian potter Toshiko Takaezu) paired with tiny medical models of the womb (19th century Dutch doctor Aletta Jacobs). In another mini-show about body augmentation, facial prosthetics for victims of war (Anna Coleman Ladd) dialogue with far-out Martian-themed costume sketches (Alexandra Exter).

Display dedicated to the facial prosthetics of Anna Coleman Ladd (1878–1939). Photo by Ben Davis.

“Corps Orbite” is the name of a room in the Central Pavilion that includes displays of concrete poetry, but also Ouija board drawings and hoax seance photos. In “The Witch’s Cradle” mini-show—which is actually not about witches, and is harder to summarize the longer you stay with it—Laura Wheeling Waring’s Black Egypt-themed cover illustrations from the 1920s for W.E.B. Du Bois’s magazine The Crisis share a vitrine with a flamboyantly pleated pink dress once worn by Surrealist Leonor Fini.

I could spend a long, long time in these galleries, which brim with stories. I went in expecting them to be clearly defined surveys of discrete alternative art histories. It turned out that they were not. In all but the gallery dedicated to light and op art by women (“The Technologies of Enchantment”), they reveal themselves to be riffs on loose themes, melting together many historical paths.

Works by Laura Grisi in the “Technologies of Enchantment” gallery. Photo by Ben Davis.

The capsule shows serve to ground this show in a long perspective and fill up the surrounding contemporary art, which is so easily experienced as ephemeral trend and commercial product, with a sense of destiny and commitment. But they also seem to be another one of the many ways that this show celebrates unexpected pairing and hybrids.

There’s a lot in the show, but here’s what’s is not in the show: there is little of the protest imagery and images of environmental loss that is everywhere in recent art; little in terms of issue-driven photo documentary or lecturing video essay; little specific evidence of current events at all (the late insertion of a work by Ukrainian folk artist Maria Prymachenko into a symbolic place in the Central Pavilion is a sort-of exception).

Maria Prymachenko, Scarecrow (1967). Photo by Ben Davis.

Indeed, the Biennale’s biggest faceplant is its most didactic essay-style film: the normally good Lynn Hershman Leeson’s video Logic Paralyzes the Heart (2022), which has something of the air of a school play made from a New York Times article about the perils of Artificial Intelligence (albeit one with a cameo by Thor: Ragnarok actress Tessa Thompson).

Temperamentally, Alemani is indisposed to the didacticism of much “biennale art.” This is part of why “The Milk of Dreams” has such a warm, inviting atmosphere overall, even at its darkest points.

Yet the lyrical texture of the show is not simply presented as a matter of preference. It’s on a mission. This is a show, Alemani says, “rooted in the post-human,” seeking to “challenge the Renaissance and Enlightenment notion of the human being—especially the white European male—as motionless hub of the universe and measure of all things.”

With this framework in mind, a lot of different levels of this Biennale snap neatly into alignment: the curatorial focus on an alternative art history of women; the emphasis on sensation, imagination, and fantasy over “message art”; the specific set of recurring images (myths, magic, cyborgs, hybrid creatures, interspecies trysts). All flow from a diagnosis of what ails civilization: a selfish, instrumental, and masculinist rationality, out to separate itself from its others and dominate them.

Ali Cherri, Titans (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

Philosopher Donna Haraway, author of both the Cyborg Manifesto and the Companion Species Manifesto (the latter less cited but much more relevant here), is the patron saint of the wall texts. But Alemani has said that the show’s intellectual keystone is actually Deleuzian feminist philosopher Rosi Braidotti’s “Posthuman Critical Theory.” It is worth dipping into the catalogue to see what this offers. It comes down to this: a program, Braidotti writes, of “redefining traditional binary oppositions, such as nature/culture and human/non-human, paving the way for a non-hierarchical and more egalitarian relationship among members of the same species as well as between different species.”

Now, this is not entirely new as a big-art-show framing device: in the first half of the 2010s, it was very trendy for curators everywhere to be into “speculative realism” and “new materialisms,” earnestly musing about whether rocks could think (Braidoti weighed in on the speculative turn in art in the pages of Frieze at the time).

I understood those pancosmic interests as a displaced reaction to the environmental crisis, as a way to seem world-altering enough to meet the times, while also being arty enough to base an art show on. Still, it often seemed to be borderline obscurantism. (Without making too much of it, I have to mention how striking it is that the first post-pandemic Venice Biennale takes aim at “Enlightenment reason” as what ails society, even though the pandemic saw a disastrous rise of anti-science thinking—as much among affluent and liberal New Age and wellness types as among conservative cowboys.)

Practically, is Braidoti’s “post-human” idea of undoing nature-culture hierarchies much more than just the realization that “we are one with nature”? Does it point us toward meaningful action, or just towards some kind of quasi-spiritual epiphany? It’s a merit of “The Milk of Dreams” that it takes its premise seriously enough to show what the stakes might be.

Among other books, the Biennale shop is selling Marxist environmental writer Andreas Malm’s hard-hitting How to Blow Up a Pipeline, whose very title stresses the need for urgent—and very definitely instrumental—action. But this is not the feeling given off by the art of the Biennale itself, whose “post-human” environmentalism is probably best illustrated by Hong Kong-based polymath Zheng Bo’s 16-minute video Le Sacre du printemps (Tandvärkstallen) (2021).

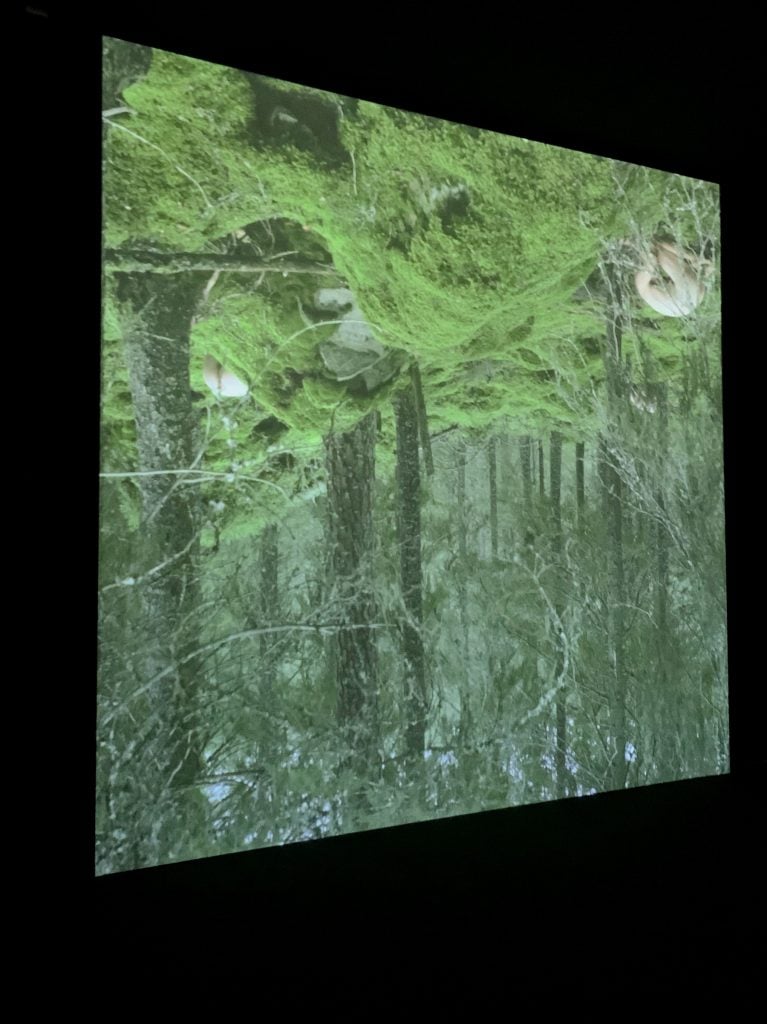

Zheng Bo, Le Sacre du printemps (Tandvärkstallen) (2021). Photo by Ben Davis.

In exquisitely respectful, static long shots, Zheng’s video presents a group of nude Nordic men dotted across a lush green woodland landscape, as they have sex not just in the forest, but with the forest—silent at first and then building to grunting, pale butts pumping in and out.

For one long passage, the men stand on their heads and writhe against the trunks. The image is turned upside-down so that the forest floor is at the top and the slender trees seem to be supporting it like pillars, a device that seems to stress that Zheng is out to flip expectations. (“Of all the set criteria for Posthuman Critical Theory…,” Braidoti writes in the catalogue, “the most important is the tactical method of defamiliarization, that is to say, disconnection of the subject from familiar and habitual patterns of identity.”)

The wall text for Le Sacre du printemps explains: “Zheng Bo is committed to all-inclusive, multi-species relationships. Through a socially and ecologically engaged art practice, he forges an alternative path that de-emphasizes a human-centric worldview and strives instead for interconnectedness of all living beings.” Elsewhere, he has said that his work emerged from his concern with climate change and his effort to explore “how plants practice politics.”

As a depiction of the delights of an eco-queer sexuality, the video is brazen and memorable (albeit a bit solemn for an erotic celebration, IMO). But if pleasuring yourself in (with?) the woods is somehow being proposed as the model for the earth activism we need now, that starts to lose me.

That starts to make it seem as if the allure of “post-humanism” represents the global intellectual classes, in despair about the possibility for human action to affect the problems weighing on the world, taking refuge in magical thinking…

I think it’s fair to raise questions. Debating the stakes of a “post-human aesthetics” will surely be part of the legacy of this Biennale.

But asking for a mission or a program is itself a very instrumental way to think about an art show. And for my money, what is great about this show’s framework is its aesthetic richness, not its philosophical rightness.

Delcy Morelos, Earthly Paradis (2022). Photo by Ben Davis.

When I think about this show, I’ll really think of thoughtfully planned, “you had to be there” details. Of Colombian artist Delcy Morelos’s Earthly Paradise (2022), at the midpoint of the Arsenale, a low-slung structure made of bales of earth. Its smell, very much part of the work, is a subtle and very pleasant cinnamon-y perfume. It may be the central “image” I take away.

Or I’ll think of the moment in Alexandra Pirici’s performance where the performers ask you to stand with your eyes closed, and hold out your hands to make a new “haptic memory.” Something soft and spiky appeared on my palm, gently turning. And, as promised, I still do have an imprint of its shape and texture and movement in my brain, without having let myself know what the mystery object was.

Or the bend in the Arsenale where three artists, all influenced by Haitian Vodou, are put together. The intricate, storybook detail of Célestin Faustin’s 1979 painting of a lush, orderly Garden of Eden stays with me as a vision of imagined plenty.

Célestin Faustin, Jardin d’Eden (1979). Photo by Ben Davis.

The tenor of the times demands a high burden to claim relevance, and the result can be a muted and dutiful tone in art institutions. If all the elastic “post-human” framework of the 2022 Venice Biennale does is to bring together a great many unexpected and deserving figures into a configuration that feels personal and purposive and greater than its parts, then it is doing a great deal, actually.

I do believe that art, like dreams, can be a resource to discover “new conditions of existence,” as Alemani promises of this Venice Biennale. Dreaming can change reality, but you don’t generally dream in order to change reality. It is enough—and it is important—that dreaming gives your mind what it needs so that you might come back to face reality refreshed.

“The Milk of Dreams: The 57th Venice Biennale” is on view at the Arsenale della Biennale di Venezia, Campo de la Tana, 2169/f, 30122 Venice, Italy, and the Giardini della Biennale, C. Giazzo, 30122 Venice, Italy, April 23–November 27, 2022.