Art & Exhibitions

In Ralph Rugoff’s Venice Biennale, the World’s Artists Take Planetary Doom as a Given, But Search for Joy Nonetheless

There is much to be disquieted by in this year's Venice Biennale, artnet News chief art critic Ben Davis finds.

There is much to be disquieted by in this year's Venice Biennale, artnet News chief art critic Ben Davis finds.

Ben Davis

The title curator Ralph Rugoff chose for his 2019 version of the Venice Biennale is “May You Live In Interesting Times.” The phrase has a suggestive backstory: It is a fake Chinese proverb, first uttered by a British diplomat in the context of the rise of fascism in Europe. So the name contains a lot in it that potentially resonates with the world as it is unfolding around us, in Italy and beyond—about representation and mis-representation, about the struggle to find metaphors to describe a world slouching ever closer towards the brink of disaster.

At the same time, Rugoff has committed his show to celebrating the “multivalent” and the “richly ambiguous,” and pitched it specifically against art as “a form of journalism.” And he has also explained that “May You Live in Interesting Times” was simply “a phrase I thought was ambiguous enough to be interesting.” Which makes me remember that saying something is “interesting” is also the most stereotypical deadly place-holding judgment about art. If you asked your friends how they enjoyed the biennial and they said it was “interesting,” you’d know they thought it was mediocre.

So, the question has to be: What does this show really say about the times we live in?

Personally, I had a more-than-interesting time at the 2019 Venice Biennale. Rugoff—a United States-born curator based in London at the Hayward Gallery, whose avuncular manner reminds me of Hugh Laurie playing an American in Veep—has put his focus on this art show as an art show rather than a thesis statement. That approach, you can see, has definite virtues from the experiential point of view.

The entrance to the Arsenale for the 2019 Venice Biennale. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

There’s certainly plenty to look at, but the roster of almost 80 artists is less overwhelming than past editions. The central conceit—curating two separate shows of the same artists as “Proposition A” and “Proposition B,” in the Arsenale space and the Giardini pavilion, respectively—is a nice way to do things. It ensures that the individual exhibitions are pleasant as statements in themselves, while also giving the mind something bigger to hold onto, as you mentally compare and contrast.

Still, ideally biennials are more than pleasant. Ideally they define a zeitgeist through the filter they put on contemporary art in general and the juxtapositions they specifically create: the late Okwui Enwezor’s 2015 version was all about the heightening of political claims for art and re-centering on the non-Western; Christine Macel’s 2017 version now seems to have been prescient in its focus on a yearning for art as healing ritual. Rugoff’s curatorial declarations about “ambiguity” do not seem that promising for the event’s trendsetting purpose. It would seem to be a non-thought about a non-theme.

Otobong Nkanga, Veins Aligned (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The interesting thing (sorry) about “May You Live in Interesting Times” is that a rather clear theme, or at least a clear mood, does seem to emerge from its constellation of art, as if unbidden, like a pattern emerging from the tea leaves.

My colleague Julia Halperin joked that it’s the “we’re all gonna die-ennial.” A thread of despair, of seeing portents of a dark future, stands out.

Jon Rafman, Disasters Under the Sea (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

This is explicitly the point of Hito Steyerl’s pair of doomy video art installations about the evils of AI and the peril of a rising sea. It is the feeling of the digital hellscapes from both Ed Atkins and Jon Rafman.

Alexandra Birken, ESKALATION (2016). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

You catch it in Stan Douglas’s photo series imagining looting and abandonment in the wake of a New York City blackout, and in Alexandra Birken’s crushed, limp human silhouettes, hanging from the beams of the Arsenale ceiling or draped over ladders to nowhere.

Yin Xiuzhen, Trojan (2012). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

It’s plainly there in Yin Xiuzhen’s giant sculpture of a seated figure with its head in its lap as if braced for a plane crash, made from recycled clothing and therefore strongly hinting at a consumer culture about to slam headlong into the consequences of its waste and obsolescence.

When I actually take the time to categorize all the art in the show according to theme, I find this overall impression is misleading. There’s actually more of what I’d call “funky formalism” or “enigmatic imagism” than art that explicitly deals with eco-tastrophe or techno-dystopia.

Nabuqi, Do real things happen in moments of rationality? (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

There are plenty of lushly hermetic, arty objects: Chinese artist Nabuqi, whose installation of a cow sculpture on a train track circling the room is meant as a funny non-sequitor; US painter Avery Singer’s brainy post-digital canvasses of hyper-abstracted faces; Indonesian artist Handiwirman Saputra’s wonky monumental sculptures; Haris Epaminonda’s gorgeous, 30-minute video Chimera, which floats placelessly through shimmering landscapes, close-ups of animals, lingering shots of cut gems.

Three works by Handiwirman Saputra. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

There are also other sub-themes that don’t seem so gloom-and-doom. There’s plenty of “poetic science project” art. That includes Ian Cheng’s quirky artificial intelligent serpent-creature, BOB, rattling around contentedly onscreen in his virtual cage, and Anicka Yi’s large lantern-like constructions dripping water and containing “animatronic moths.”

Anicka Yi, Biologizing the Machine (tentacular trouble) (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

That’s how I’d also categorize Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s psychedelic virtual reality experience (sadly, a real disappointment once you wait through the long line), and Antoine Catala’s amusing installation The Heart Atrophies, which has a plastic letter “A” hooked up to a pump so that it pulses in and out like a living thing.

Antoine Catala, The Heart Atrophies (2018-2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

And yet even so and still, the “end times” impression lingers.

And as I went back over the whole thing, I realized that it is partly textual. Aside from phrasemaking about the virtues of ambiguity, the show labels find portents where you wouldn’t necessarily see them.

Lee Bul, Aubade V (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Thus, Korean artist Lee Bul’s Aubade V (2019), a steel-and-LED construction that looks like a radio tower, flashes a text that, we are told, “seems to imply that the earth will survive catastrophic climatic upheaval.”

Works by Gabriel Rico. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

And then there’s Mexican artist Gabriel Rico’s fussy found-object constructions, which look like typical bits-and-bobs contemporary sculpture to me. The text says they “address the relationship between environment, architecture, and the future ruins of civilization.”

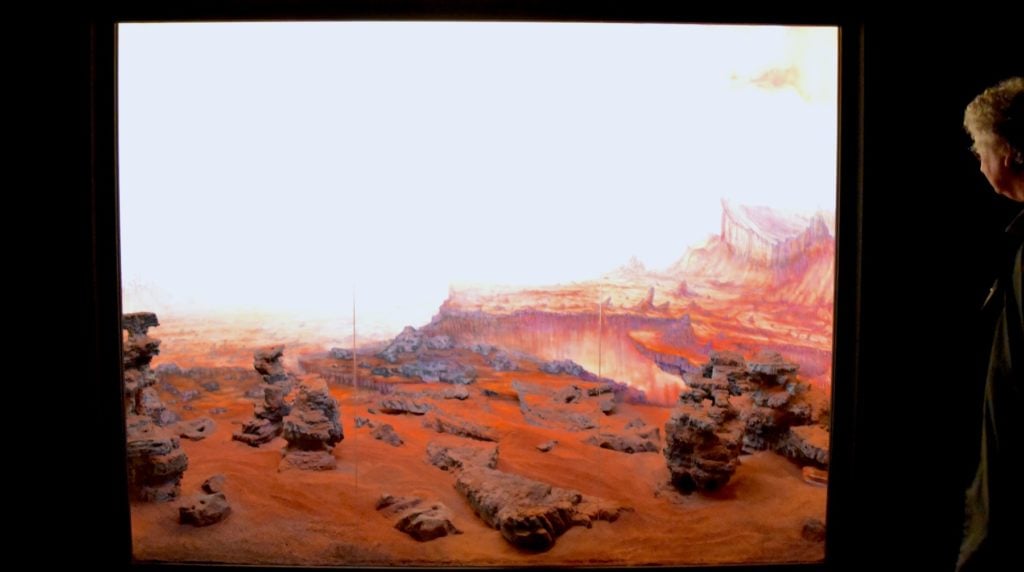

Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster, Joi Bittle (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

And over in the Giardini pavilion, Gonzalez-Foerster’s diorama of a barren Martian landscape (complete with a copy of Ray Bradbury’s Martian Chronicles nearly hidden beneath a red rock) is explained thusly: “At a time when a looming climate crisis threatens life on Earth, her attention has turned to Mars.”

And so on. There’s more.

This is just atmosphere, really. We can take Rugoff at his word that he has not tried to curate a thematic biennial. (He actually expressed surprise, at the official press conference, that a journalist had suggested that there was a motif of evil tech in the show.)

But that, in a way, is the striking thing about it: the sense of doom just organically emerges from what he has thought of as “interesting,” rather than being a theme he has selected for. Which seems to point to the fact that future civilizational collapse has now become hegemonic within the imagination. This premonition isn’t a theme anymore; this is just the context in which all art takes place.

Does “May You Live in Interesting Times” offer anything like hope?

Teresa Margolles, Mura Cuidad Juárez (2010). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

There are works that actually do propose very specific objects of critique (Lawrence Abu Hamdan, Teresa Margolles, Rula Halawasi), and therefore suggest potential for the rallying power of critical thinking.

There are a number of works that propose various kinds of upcycling or recycling as a strategy (Neïl Beloufa, Zhanna Kadyrova, Andra Ursuţa). And a number of works incorporate this or that model of prosocial activity as part and parcel of their aesthetic project (Gauri Gil, Christine and Margaret Wertheim, Augustas Serapinas).

Christine and Margaret Wertheim, works from the “Pod World” series (2006-2016). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

But most of the positive energy is carried, here, by the notion of “redemptive representation.” The coolest spin on the theme may be LA-based filmmaker Kahlil Joseph’s BLKNWS project, installed at various sites around the two shows, which imagines an experimental news channel, equal parts funny and brainy and bracing, about African American culture.

Korakrit Arunanondchai, No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5 (2018). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

The most complex spin on the theme may be Korakrit Arunanondchai’s lavish three-channel video installation No history in a room filled with people with funny names 5. It juxtaposes meditations on how media coverage of the 2018 Thai cave rescue bolstered conservative politics in Thailand with footage of the glam, intense performance artist boychild, an icon of post-gender aesthetics—as if to say that thinking beyond the rigid conventions of gender might also promise a way to think critically about the media.

A huge part of this show is about minority voices, of various kinds in this global show, carving out space to claim a new visibility. Over and over, there are self-portraits with the gaze leveled out at the viewer, a sign of self-conscious assertion.

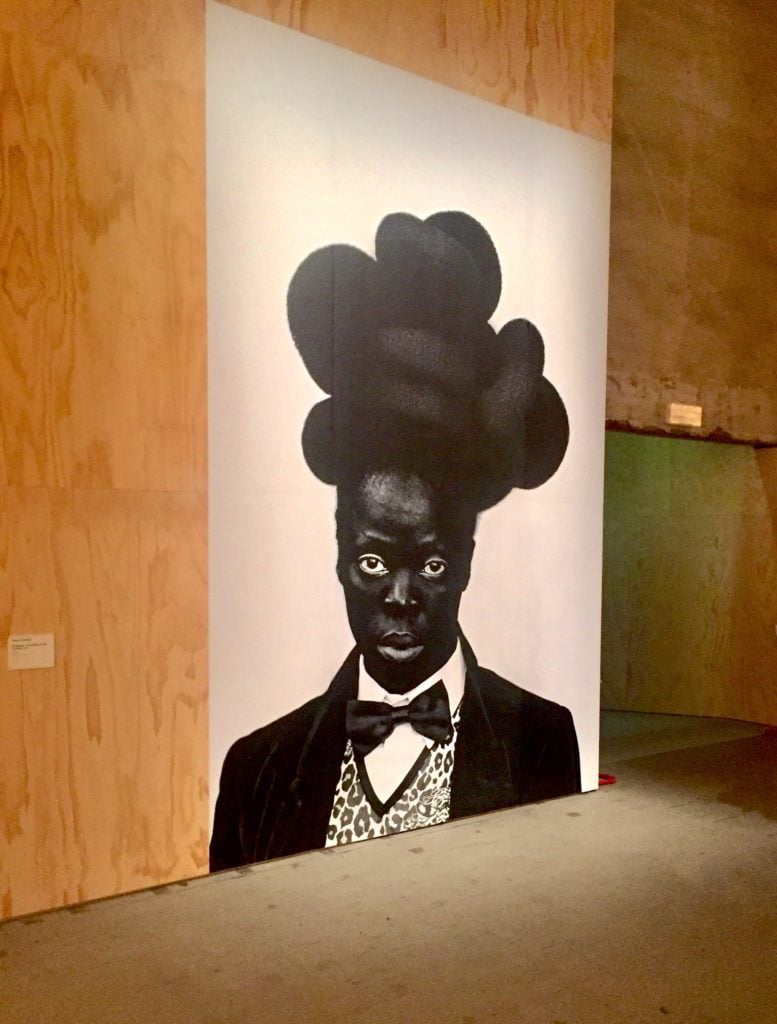

Zanele Huholi, Phaphama, at Cassilhaus. North Carolina (2016). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

In the Arsenale, South African photographer Zanele Muholi’s starkly black-and-white blown-up self-portraits stand as punctuation marks throughout the show.

Martine Gutierrez, Body En Thrall. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

Then there are the witty, canny set-up self-portraits from Martine Gutierrez’s Indigenous Woman magazine project, aping the look of fashion magazines or playing with archetypes—a real highlight.

Japanese artist Mari Katayama, born with a condition that led her to have her legs amputated at a young age, depicts herself striking various poses, highlighting what would likely be branded as a disability via various creative prosthetics and props, as if to show it as a source of creative strength.

This is a major and accelerating current in contemporary art. Surveyed here in such prominence, but so close to the apocalyptic stuff, you realize that its deployment might have a double meaning: on the one hand, it is about giving overdue space to once-sidelined kinds of identities within the Euro-American art industry; on the other hand, it is freighted with that same art industry’s desperate hunger for some kind of redemption narrative, some kind of anecdote to its own depression, some excuse to feel good.

Arthur Jafa is ahead of the curve of critique here in his video The White Album, seen here in the Giardini space. Jafa became a sensation a few years ago with Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death, a found-media video collage about black life—and black death at the hands of white people. But amid the turbo-charged wave of praise, the artist has said that he began to find it too automatic, as if images of black suffering were being consumed as a tool to have an emotional catharsis: “People were getting this eight-minute epiphany,” he explained. “Even when people said, ‘Oh I cried,’ the very cynical part of my brain suspected some kind of arrested empathy with regard to the experience of black folk.”

So here, in this follow-up, Jafa has turned to catalogue the imagery of whiteness in his raw internet-surfing style. Among other things, we see clueless YouTube pundits, a sinister paramilitary type, and his own dealer Gavin Brown, whose face lingers on the screen, scrutinized, as if it were a synecdoche for the gatekeeping establishment.

Arthur Jafa, The White Album (2019). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

At one point, there is a clip of the bleachers at a Celtics game. As Bon Jovi’s anthem Living on a Prayer blares, the camera alights on a young man, exuberantly dancing and singing along, becoming more and more over-the-top and comical as he realizes the camera is on him. (In fact, we know that his name is Jeremy Fry; the clip is from 2009.)

This is one of those viral moments that seem like pure joy when you discover them on the internet—but Jafa juxtaposes it closely with chilling, becalmed security camera footage of the murderous Dylann Roof, entering and then, a beat later, leaving the site of the 2015 massacre at the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston.

Now, as a fellow awkward white guy, I identify with the embarrassing dancer. The juxtaposition of his abrupt eruption of exuberance with Roof’s sociopathic coldness, just before he commits methodical racist violence, brings me despair—as if the one outburst connected, symbolically, to the other. Somewhere in the background, Jafa is probably also making a connection to the over-effusive reception of Love Is the Message, The Message Is Death.

What I take the artist to be saying is that, no matter how pure you think your reaction is, you are caught in the symbolic web. There will be no symbolic redemption for the evils of the world—not on the level of consuming images, at least. In that way, The White Album’s aura radiates out through the whole show, troubling it all, asking what exactly it is its audience finds interesting in these times, and why.