Every Monday morning, artnet News brings you The Gray Market. The column decodes important stories from the previous week—and offers unparalleled insight into the inner workings of the art industry in the process.

This week, assessing a late-breaking case of museum mayhem….

SAY GOOD-‘BI’

On Friday and Saturday, eight participating artists publicly requested that their works be withdrawn from the 2019 Whitney Biennial. And the exodus suggests that it is time for the art world to apply a new caveat to the way it has traditionally documented and valued artists’ careers.

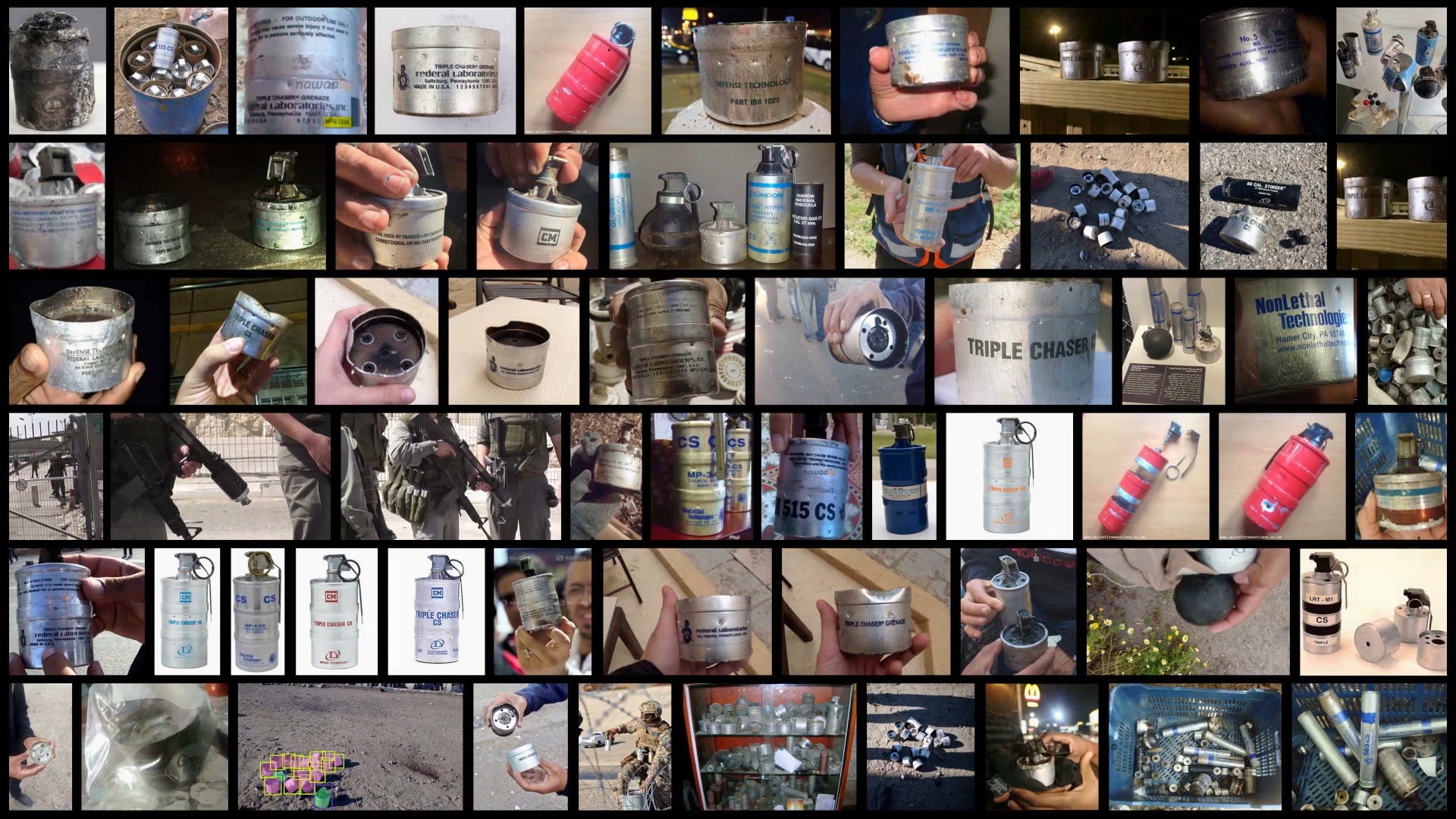

This new chapter opened on July 19 with a letter written by Korakrit Arunanondchai, Meriem Bennani, Nicholas Galanin, and Nicole Eisenman, which the signatories addressed to the biennial’s co-curators and published online at Artforum. At its core was the request that their works be extracted “for the remainder of the show” as a “condemnation of Warren Kanders’ continued presence as Vice Chair of the Board,” on account of his status as majority owner and chief executive of Safariland, one of the world’s largest manufacturers of tear gas and other “defense products.”

On Saturday, four more WhiBi artists—Agustina Woodgate, Christine Sun Kim, Eddie Arroyo, and the research collective Forensic Architecture—announced their intent to follow the original quartet out the museum’s doors. News of Woodgate, Sun Kim, and Arroyo’s defection broke wide via a New York Times report in which all three echoed the concerns, and in some cases the specific language, of the letter from Arunanondchai and company.

Later in the day, Hyperallergic reported that Forensic Architecture had also informed the exhibition’s curators that it would vacate the show. However, the group simultaneously asked that Triple-Chaser, its original biennial contribution, be replaced with “new evidence they’ve found that directly links” Kanders-backed products with possible war crimes. (It was not clear by publication time how each request could be granted without canceling out the other.)

In the event that you are only now emerging from a relatively extended descent into cryostasis, the Kanders controversy erupted last fall with a Hyperallergic piece linking him to Safariland and, crucially, Safariland to the tear gas used to repel migrants from a Tijuana-California border checkpoint in November 2018. This revelation has been followed by a steadily building hurricane of anti-Kanders activism, including separate open letters—one from the Whitney’s staff, another signed by more than 120 scholars and critics, and a third signed by over half of the biennial’s participating artists—as well as, more visibly, an escalating series of protests, all advocating for Kanders’s resignation or removal from the Whitney’s board.

If the requests of the exhibition’s eight departing artists were all to be granted immediately—a more realistic possibility for Arunanondchai’s video and Galanin’s lone tapestry than Eisenman’s monumental mixed-media sculptures—their works would exit the show almost exactly at the midpoint of its four-month run. And it is the timing of their about-face that creates a conundrum for the art world’s normal ways of operating, both inside and outside the market.

Nicole Eisenman, Procession, 2019. image courtesy Ben Davis.

PREMATURE EVACUATION

Although none of the exiting artists cited it as the catalyst for their respective reversals, an Artforum essay titled “The Tear Gas Biennial” hit the internet the day before the first four artists requested their works be withdrawn. Penned by artist and writer Hannah Black with the magazine’s Tobi Haslett and Ciarán Finlayson, the piece skillfully builds the case against both Kanders and various popular counterarguments justifying continued participation in this year’s biennial.

It’s a powerful piece of work, and no matter what the departing artists say (or don’t), it seems unlikely to me that the essay’s publication played a strictly incidental role in their decision. (For a recap of why Black’s testimony might carry outsize impact in the court of WhiBi ethics, remember her searing, widely co-signed open letter about Dana Schutz’s scandal-igniting Open Casket during the exhibition’s 2017 edition.)

As Black and her collaborators mention in the essay, resistance-minded artists have withheld or withdrawn works slated for prestigious exhibitions before. Most recently, they point to the 2014 Biennale of Sydney, from which multiple artists quarantined their contributions to pressure the show’s organizers to sever ties with Transfield Holdings, a major sponsor contracted by the Australian government to operate immigrant detention centers. The biennale did, and its chairman, who doubled as a Transfield executive, resigned.

The authors also point back to the 1970 New York Art Strike, inaugurated by Robert Morris’s premature shutdown of his own solo exhibition at the Whitney in response to a series of governmental affronts ranging from the Kent State shootings to violent suppression of black rights in the American south to the Vietnam War’s mission creep into Cambodia. As part of the same strike, Adrian Piper also withdrew her work from a solo exhibition at the New York Cultural Center, substituting a written statement that framed her move as “as a protective measure against the increasingly pervasive conditions of fear.”

Of these examples, Morris looks to me like the best predecessor of the eight artists who have now pulled the ripcord on their participation in the 2019 biennial. He’s the only one to actually claw back work that was already on view after an ethical turning point. The Biennale of Sydney artists withheld their work before the show opened, not after, and although the details are still a little hazy to me based on what I could find over the weekend, Piper appears to have done the same. (Her CV, current as of September 2011, lists “One Man (sic), One Work” at the New York Cultural Center in 1971, which may or may not be the same exhibition that received her “fear” statement instead of more traditional work.)

Installation view of works by Eddie Arroyo at the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

QUIZ SHOW

This comparison also unleashes a flood of questions about how to understand, memorialize, and value the short-lived participation of the eight departing WhiBi artists.

First off, should we view their gesture as equivalent to that of Michael Rakowitz, the lone artist to publicly reject the Whitney’s invitation to the 2019 biennial? Almost certainly not. Rakowitz never agreed to participate in the show, let alone produced or exhibited any work there. He simply said “no” at the outset.

The opposite is true for the others. Even if they were to demand the museum retroactively erase their presence from the show’s internal archives—none of them has yet, and I doubt that will change—external sources would still document their participation. Their work has been cited in published reviews and other press. It appears in the exhibition’s printed catalog and marketing materials. Untold hundreds or thousands of visitors have included it in social-media posts. It can never be fully expunged from the public record.

So should the evacuating artists scrub the 2019 Whitney Biennial from their CVs—and demand that their galleries do the same? This too is odd territory. Again, it seems absurd to deny having done something when an armada of evidence can prove otherwise. But if they want to divest themselves of the show as completely as possible, self-editing their history is at least something they themselves can do, similar to the way Gerhard Richter has disavowed early works he no longer wants to be a part of his narrative.

And yet there is very little precedent for doing so amid the examples in “The Tear Gas Biennial.” Morris’s CV, current through January 2019, still lists the 1970 Whitney show he closed mid-run. And only two of the nine artists who threatened to boycott the Biennale of Sydney on ethical grounds, Charlie Sofo and Gabrielle de Vietri, appear to have stayed out of the show after the expulsion of Transfield Holdings, according to the catalogue and the artists’ CVs. Which leads us to perhaps the thorniest aspect of this situation from both a historical and a commercial standpoint….

Nicholas Galanin, White Noise, American Prayer Rug, 2018, at the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

ON SECOND THOUGHT

The dilemma here, as smart people both inside and outside the art market vocalized over the weekend, is that the departing artists arguably get the best of both worlds, at least as judged by traditional art-world standards: all the prestige and value-accumulation that comes from having participated in the Whitney Biennial, and at least some of the moral authority that comes from having withdrawn from it.

To be clear, I am not—repeat, not—accusing these artists of cynically trying to game the system. The situation already looks torturous enough from my vantage point as a straight white guy with an industry-sanctioned platform and the luxury of some distance from the issue. I can’t imagine what it feels like to be inside this gauntlet, especially as someone with less privilege than I enjoy through the sheer randomness of the cosmos.

Still, we can’t ignore that the departing artists have to some extent discovered an escape hatch that also happens to have a treasure chest inside. Even setting aside the press and publicity materials already produced, other curators, dealers, and collectors have seen their work in the biennial, and at least some sales and future shows have undoubtedly been lubricated by its inclusion. These details make the evacuees’ careers fundamentally different from either Rakowitz, who rejected the museum outright, or the other 67 artists who remained in the show as of this weekend.

In fact, it’s even arguable that the eight evacuees have inverted the cost burden of the exhibition for their fellow artists. Before the publication of the biennial’s artist list, invitees were sacrificing something (a valuable career opportunity) by opting out. But once the first four artists withdrew mid-stream, the remaining artists may be sacrificing something (their reputations among many of their colleagues) by continuing to opt in. In essence, it is an amplified, higher-stakes sequel to the participating artists’ petition to remove Kanders prior to the biennial’s opening—which, again, nearly half the potential signatories chose to ignore.

So how does the art world at large deal with this twilight zone, in which artists both participate in and withdraw from prestigious exhibitions? Right now, the only guidepost I can think of is, perhaps weirdly, the greatest modern scandal in… Major League Baseball.

Agustina Woodgate, National Times (2016/2019) at the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Image courtesy Ben Davis.

THE ASTERISK ERA

Even people who would never consider themselves MLB fans know about the so-called Steroid Era: a roughly 30-year epoch between the late ‘80s and late 2000s during which evidence and testimony suggest many records were set thanks to players’ use of performance-enhancing drugs (PEDs).

As a category, PEDs encompassed everything from human growth hormone for quicker recovery to anabolic steroids for increased strength. Yet league officials didn’t ban steroids until 1991 or initiate mandatory drug testing until 2003. In other words, the rules were late-arriving, soft, and easy to break. Very few violators were ever caught. Their penalties were generally relatively light.

Most importantly, the records set during the Steroid Era remain in place to this day, even though revelations about the widespread use of PEDs effectively calls into question every athletic feat achieved during those years. For the most part, the players responsible for them can be neither definitively confirmed as clean nor definitively rejected as dirty. Which makes them too compromised to fit comfortably within the rest of baseball history, yet too important to exclude. They are simultaneously present and absent—lodged in a purgatory that many, if not most, baseball analysts agree should be marked in a specific way.

That way hinges on the asterisk. Anti-PED hardliners insist that asterisks should be affixed to every record set during the Steroid Era, as a symbol that says, “This thing is not quite like the others.” The historical record stays intact, but it also reflects the unique complications of the age.

Maybe the 2019 Whitney Biennial ushers in the Asterisk Era of institutional exhibitions: a time in which unprecedented access to information about museums, their boards, and their affiliations elicits unprecedented pressure on artists to withhold or withdraw works from shows at any point.

Setting aside the exhibition’s history as a political flashpoint in the art world, the 2019 Whitney Biennial is no longer extraordinary. Major institutions around the world—and the artists who partner with them—are now being judged guilty by their association with opioid producers, fossil fuel giants, private prison companies, cyberweapons firms, and many other offenders. In short, the pressure is not going away. If anything, the vise will only tighten as it produces more actual change.

Meriem Bennani, detail of MISSION TEENS: French school in Morocco (2019) at the 2019 Whitney Biennial. Courtesy of Ben Davis.

To be clear, asterisks for the Steroid Era are an imperfect analogy, but the imperfections are the point. If added to the record books, they would mark individuals who in some sense benefited from within an ethical gray zone. Asterisks in the art world—which could hypothetically be applied to artists’ CV entries for any show from which they pulled out late—would do the same.

They would notate that some informed observers view the outcome as tainted, while others simply view it as symptomatic of a time in which the rules of the game were in flux. They would add nuance to the historical record while acknowledging that, in the moment, the market had to accept the circumstances as they were. Just as the 2001 San Francisco Giants had to pay big money for Barry Bonds, who suddenly broke the all-time home-run record at age 36 despite obvious suspicions about his “training regimen,” collectors have to pay the increased market rate for artists included in prestigious institutional exhibitions knowing they could vacate the show at any time after it opens.

Would asterisks do more than solve an art-world record-keeping problem, though? And is it possible the decision to pull out will only heighten these artists’ reputations as key players in a major moment in museum history, transforming that asterisk into a gleaming halo? Finally, should we even be spending time on such possibilities at all in light of the need for structural reform in the institutional sector?

Right now, I think the answer is “yes,” because how we define and visualize an issue determines how we try to think through it. But given the recent trajectory of art activism, as well as the rising stakes of problematic patronage affiliations, it’s something we all need to spend more than one wild weekend considering.

That’s all for this week. ‘Til next time, remember: even if you’re through with the past, the past may not be through with you.