Have you ever wondered what your rights are as an artist? There’s no clear-cut textbook to consult—but we’re here to help. Katarina Feder, a vice president at Artists Rights Society, is answering questions of all sorts about what kind of control artists have—and don’t have—over their work.

Do you have a query of your own? Email [email protected] and it may get answered in an upcoming article.

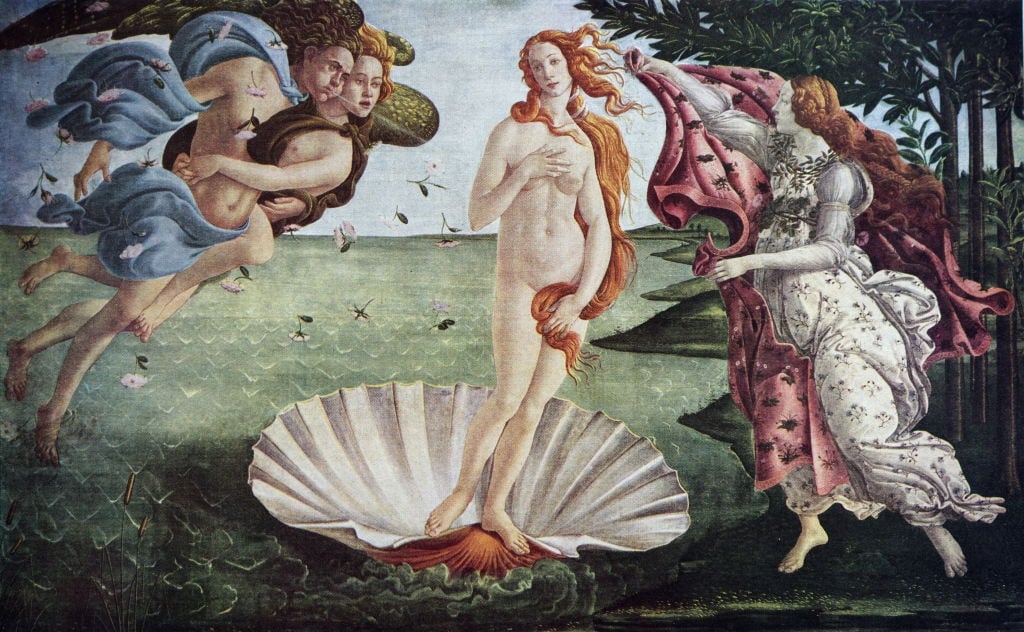

I read that the Uffizi is suing Jean Paul Gaultier over the fashion house’s use of Botticelli works on some t-shirts. I always thought that long dead artists like Botticelli were in the public domain. How is this lawsuit even able to happen?

I love a reader who knows her intellectual property. It allows me to go a little deeper from the jump. This one is for all the real IP heads out there!

When I speak about copyright expiration, I always try to be clear that I’m talking about the United States, where copyright lasts for 70 years past the death of the creator. But there are all kinds of exceptions within that—what about pseudonymous/anonymous works?—and when you start extending your focus internationally, well, we’d be here forever.

So now you have a French fashion house being sued by an Italian museum for appropriating the work of a long-deceased Italian artist. You can see extensive photography in Artnet’s write-up of the lawsuit. The “Le Musée” capsule collection bases its designs on The Birth of Venus, The Three Graces by Peter Paul Rubens, and Michelangelo’s The Creation of Adam.

Italian copyright law actually takes a page from America’s book and expires after 70 years, but the problem here is Italy’s Cultural Heritage Code, which protects its publicly owned artifacts. The Uffizi is a public institution—some say the world’s first, after having been founded by the Medici family in the 16th century. That means borrowing their material without remuneration is the equivalent of robbing the Italian people. The Guardian reports that damages in this case may even exceed €100,000 ($103,000). Stay tuned…

Actor Arnold Schwarzenegger on the set of Terminator. Photo: Sunset Boulevard/Corbis via Getty Images.

I’ve been rewatching James Cameron’s movies in anticipation of the Avatar sequel and couldn’t help noticing that in the credits for The Terminator it says “Acknowledgement to the works of Harlan Ellison.” As a fan of Ellison’s novels, I thought the connection between them and Terminator was always pretty obvious, so why such a small credit? What’s this about?

While I have seen the Terminator movies, I have not read or seen anything by Harlan Ellison so I can’t speak to the obviousness of the connection, or to its quality. Indeed, doing so might make me feel a little like Frank Sinatra in that famous Gay Talese piece, where he taunts Ellison by saying his movie is bad, despite the fact that it hasn’t come out yet.

But I did a little research. From what I gather, in 1984, someone told Ellison that the Terminator script was similar to an Outer Limits episode called “Soldier,” which Ellison had adapted from his own short story, “Soldier Out of Time.” It was even reported by one of Ellison’s friends, Tracy Torme, that on the set for The Terminator, writer/director James Cameron said, of his research: “Oh, I ripped off a couple of Harlan Ellison stories.”

Likely perturbed by this information, Ellison inquired with the production company about the supposed similarities but did not receive a response. So, after sneaking into a preview of the film—he suspiciously wasn’t invited—he determined that there was enough overlap between The Terminator and his own work to claim that Cameron had committed copyright infringement.

Ellison said: “It was not my desire to find a similarity. I was sitting in there thinking, ‘Please don’t let it be.’ But if you took the first three minutes of my ‘Soldier’ episode and the first three minutes of The Terminator, they are not only similar but exact. By the time I left the theater, I knew I had a case against someone who plagiarized my work.”

Not only do The Terminator and “Soldier” begin with nearly identical scenes—laser beams flash across a desolate landscape—but they both feature an entity from the future, programmed to kill people, who is sent back in time to the mid-20th century.

In my Harlan Ellison deep dive, I learned that another episode of The Outer Limits written by Ellison, called “Demon with a Glass Hand,” also features a robot from the future, that believes itself to be a man, sent back in time to save humankind. Also, Ellison’s novel I Have No Mouth, and I Must Scream is about a master computer that becomes sentient and tries to wipe out the human race. All this is to say that I don’t think you need to be a Myles Dyson-level genius to see why Ellison was annoyed, sitting there in his Terminator screening.

Some people nerdier than me have suggested that the similarities alone were not so bad and that Ellison might have granted permission for free and without complaint had Cameron acknowledged his inspiration. Might Cameron have watched and read enough by Ellison that some of the themes and motifs naturally seeped into his unconscious, and unintentionally appeared in his own work? I’m sure many if not all creators are guilty of this on some level.

Perhaps motivated by Cameron’s bragging, Ellison launched a complaint—though an official lawsuit was never filed—and the issue was settled out of court, which resulted in the “acknowledgement” and somewhere between $65,000 and $400,000 in a settlement. Whatever it was, that’s a paltry amount compared to the amount the Terminator franchise has made over time, and Cameron has complained that this was a nuisance suit. He has a point. Plot is not eligible for copyright so the similarities I mentioned, though stark, may not have mattered that much.

It is perhaps appropriate that all this sturm and drang resulted in nothing more than a small fee and a tepid line buried in the credits. Isn’t that the point of the Terminator franchise, which demonstrates in each movie that all the time travel in the universe can’t change your fate?

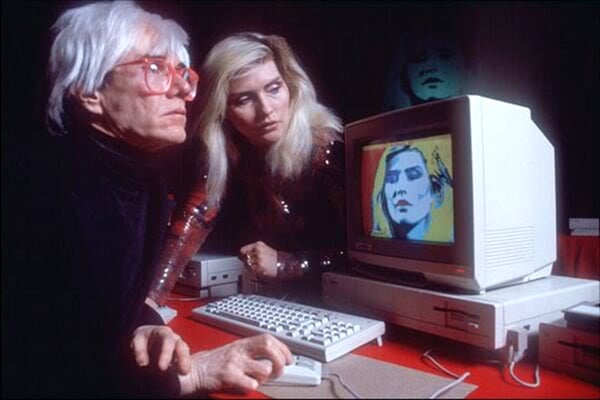

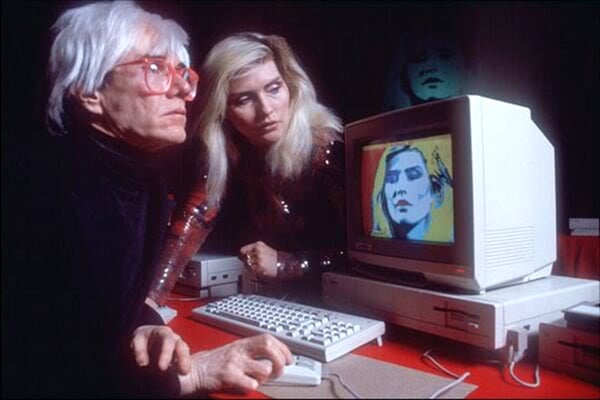

Andy Warhol and Debbie Harry using ProPaint on the Amiga 1000.

Via the Computer History Museum.

I own some 35mm slides of important early digital artwork, output in the 1980s directly from the computer. I understand that the copyright is owned by the original artists, but would like to show the work in a gallery. As the items are so small, they are hard to display. I presume I am not allowed to make a large print from the slide without permission, but if I use an old slide projector, is that considered a reproduction, or just a different way of viewing the original?

Good on you for recognizing that the original artist owns the copyright here. But you’re also planning to show another person’s artwork in a gallery, regardless of whether you make a print from the slide or choose to show it via a projector. Maybe the projector route feels a little less icky to you, because there’s no way someone could buy a light projection on the wall. Nostalgic good vibes notwithstanding, this is an artwork you did not make, for which you do not own the copyright.

Now for the good news: There’s nothing in copyright law that says you can’t show work you didn’t make at a gallery show. Museums and galleries, after all, don’t own the copyright for the works they show. They’re only showing the works they own physically, or have asked the owners to borrow (the artist being the “owner” of their new work).

I tried to find an example of an artist suing when their work was shown in a gallery or museum setting without permission. I came up empty, aside from this 2020 Cady Noland lawsuit over the display of some of her work in Germany, but that was more about conservation. The fact is, most artists want their work to be seen—they just tend to like to know about it in advance.

A 2015 report by the Center for Media and Social Impact found that copyright concerns in exhibition planning is a salient issue without a lot of case law. The art world, they found, is a “permissions culture,” where not much proceeds without approaching the artist, either for fear of lawsuits or burning bridges. I suggest you track down the artist or her estate before you display your slides at this show. That way, you may even be able to sell something, should you meet another enthusiast of old-school digital art at your opening. Just make sure you give the creator their fair share.

High Museum of Art campus. From left: the Memorial Arts Building, Table 1280, Anne Cox Chambers Wing, Wieland Pavilion and Stent Family Wing surrounding the Sifly Piazza. House III by Roy Lichtenstein and The Shade by Rodin in foreground. Photo courtesy of High Museum of Art.

Hello! I’m an Atlanta-area model and in February 2019, I went to the High Museum of Art and did a photoshoot with a photographer I know based in the city. In November that year, the photographer reached out to let me know that the High Museum was working on an advertising campaign, and was interested in using one of the photos from our shoot. In March 2020, the photo was posted in numerous billboards, newspapers, and magazines all around Atlanta. I did not sign a release form granting them permission to use the photo, although the photographer did. The campaign was to remain up until May 2020. Fast forward to September 2022, and the photo can still be seen all over the city. The more I think about it, the more I believe I should be compensated for the situation, as the photographer claims he received some benefits, but did not want to tell me the details.

Museum marketing can be pretty weird these days. The art tends to take a back seat to attractive and well dressed people hanging out or thoughtfully journaling, scenes that probably don’t accurately represent the museum experience for the majority of people. Where are the screaming children? Where are the selfie sticks? I try to go on weekday afternoons.

I’m very sorry to hear about this frustrating situation, it sounds like it’s been eating at you. Your question concerns that unique element of intellectual property that we call personality rights or right of publicity. Whereas most other areas of IP, like trademark and copyright, concern things that a person makes, right of publicity is about you and the image you put into the world, an outgrowth of your First Amendment rights.

It’s the reason signs are posted when you enter a concert where documentary footage might be filmed, and it can even apply to voices, as Tom Waits and Bette Midler have successfully sued over sound-alikes in commercials.

My favorite right of publicity case involves the actress Kathrine Heigl suing Duane Reade for $6 million when they Tweeted a paparazzi photo of her entering the pharmacy saying that it showed that real New Yorkers loved the store. Don’t get it twisted Duane Reade: we use the store, but we certainly don’t want anyone to see us stumbling out of it with toilet paper. New York actually just beefed up its right of publicity laws to protect images of the dead, so you won’t see a digital Ray Liotta selling motor oil anytime soon. Or not without the consent of his estate, anyway.

I point out this update because, unlike copyright and trademark, right of publicity is not federally guaranteed but enacted state by state. It is of particular interest in states with a lot of celebrities, like New York and California, and so it exists for everyone who lives in those states. In Georgia, it only exists under common law, so I’m not sure how it’s enforced. I’m not a lawyer, but to me it seems that the spirit of the law would reflect that you should have been paid.

Unlike the Duane Reade situation, I would say that your beef here is with the photographer, not the museum. If he had proposed shooting something commercial with you—say, an album cover—you would have negotiated a modeling fee and negotiated a proper contract regarding the use of your likeness. That’s not what happened. You embarked together on what sounds like an artistic endeavor, and then, I assume, he posted it on his Instagram and lucked into a payday when the High saw the photo and asked to use it.

I wouldn’t sue him, because it’s not likely that he received that much money and you might be past the statute of limitations for such kind of civil actions in Georgia. But I think you should make a personal appeal, if only for the sake of your peace of mind. Send him this column if you have to. Ask him to make this right. People can surprise you, they often want to do the right thing.