People

‘I Make These Beautiful Mistakes’: Nathanaëlle Herbelin on Her ‘Bad’ Paintings and the Sublime Ones Collectors Can’t Get Enough Of

The artist’s quiet figurative work has been stirring tastemakers in Paris and beyond.

The artist’s quiet figurative work has been stirring tastemakers in Paris and beyond.

Devorah Lauter

Nathanaëlle Herbelin can be found with her paint palette, hunched in the heat of the Negev desert against crumbling rocks, or in her northern Paris apartment on a typically gray day, where she captures the intimate life of things, and those around her. To free herself of ever-accumulating ideas, she will paint just about everywhere, she told me when I caught up with the French-Israeli painter. At the time, she was ensconced in a spacious studio in the Bronx, New York, where she was wrapping up a productive residency—demonstrated by the slew of new works around the room, some of which revealed her playful sense of humor (the artist requested I keep the unfinished works “between us”).

Herbelin makes uncanny renderings of experiences drawn from her own life, often laden with “ghosts” or pentimento figures of birds, faces, and scenery lurking from behind washes of pigment. The resulting panoramas of the mind have earned her a dedicated, and growing, fanbase.

Represented by Jousse Entreprise in Paris, she has caught the attention of the art world. Her paintings, sometimes compared with Morandi’s, or evocative of Danish artist Vilhelm Hammershøi, are “extremely solicited,” by institutions and collectors alike, said Sarah Nasla, the artist’s liaison. (The artist said her roots in the warmer Israeli climate contrast her paintings with Hammershøi’s, but she “feels him emotionally … the light between every hair of the brush.”)

Her work has been shown at institutions in Europe, China, and Israel, and is in the collections of major institutions including SMAK, FRAC Champagne-Ardenne, Lafayette Anticipations, and the Pinault Collection. She has shown with Emmanuel Barbault Gallery in New York, and will be included in a group exhibition curated by Florian Krewer at Michael Werner in March 2023.

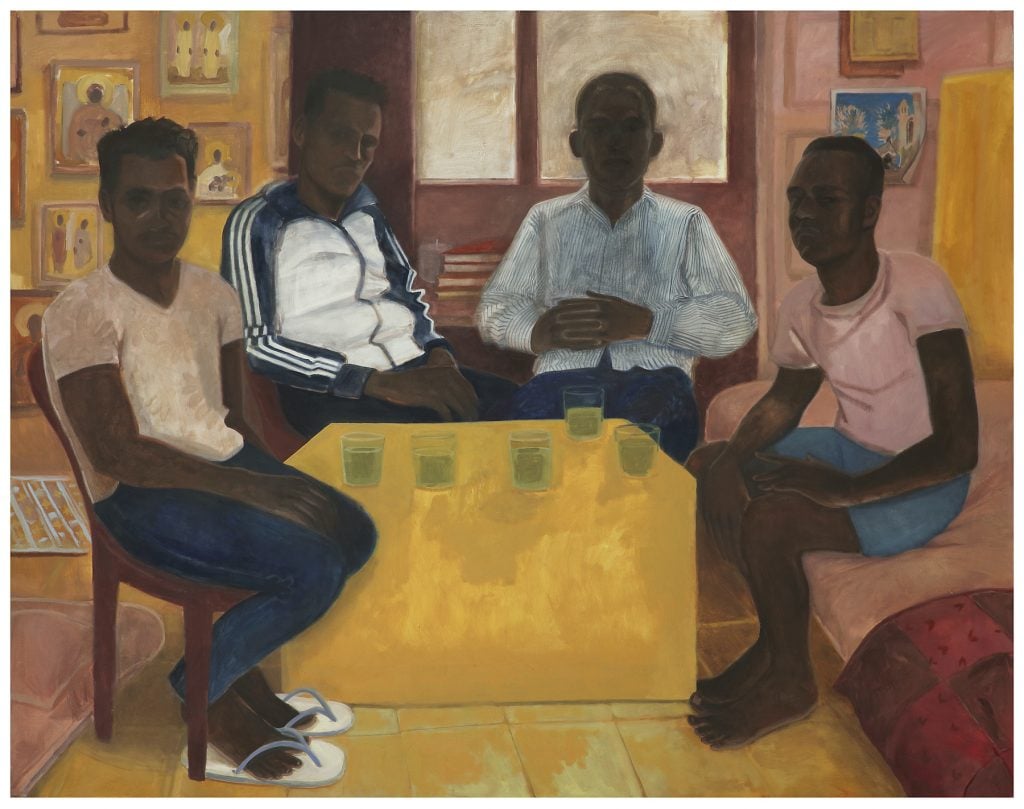

Nathanaëlle Herbelin, Michel, Emmanuel, Berhe and Zina, Levanda 1 (2020). Courtesy the artist and Jousse Entreprise.

Born in 1989 in Tel Aviv to an Israeli mother and French father, Herbelin lives between the two countries, and paints what she knows. Her gestural works in thinly scraped or brushed oil on canvas or wood, take us inside apartments in Paris and Tel Aviv, placing us at eye level, to lock gazes with a friend, neighbor, lover, or sister (with whom she occasionally collaborates, and hopes to do more). Elsewhere, she paints en plein air in the Negev desert, depicting landscapes and Bedouin tents, or in her hometown, a strawberry field about to be destroyed by a building project.

Her from-life method is performative, physically demanding, and key to her process. It “makes the conditions so complicated and sometimes you have to paint so fast, that it will make awkwardness that is … so human,” Herbelin told Artnet News. “I make these beautiful mistakes … That’s what makes the painting more moving,” she added, referencing similar distortions in Alice Neel or El Greco’s paintings.

In more recent, critically acclaimed works featured in Paris + by Art Basel in October, Herbelin’s pentimento forms originated from “failed” paintings she had revisited. For years, Herbelin said she gave her French grandmother all her “bad paintings that didn’t work,” which were promptly hung all over the house. When her grandmother passed away recently, Herbelin got back “a treasure … of awful paintings.” She began transforming these old obsessions into narrative underlayers, as in the haunting, Mental Landscape (2021), which sold for a price in the range of €28,000–€30,000 (along with eight other paintings priced between €8,000–€10,000; €13,000–€18,000; or €28,000–€30,000) by the end of the second day of the fair.

Nathanaëlle Herbelin, Mental Landscape (2021). Courtesy the artist and Jousse Entreprise, Paris. Private Collection.

Herbelin is easily her own toughest critic, and she approaches her own work with self-deprecating humor, balanced with youthful, matter-of-fact confidence. “I’m pretty happy with everything I’ve made, including one big, shitty painting,” she said of her N.Y. residency, where she spent much of her time painting, seeking out Giotto at the Met, and looking for food while pregnant with her first child. When I apologized for not having seen all of her work yet, she answered in a beat: “I’m glad you haven’t.”

While she’s as ready to point out “good” paintings and her “power” as an artist, maintaining the freedom to experiment through aforementioned “shitty” paintings is something Herbelin cherishes, despite any outside noise or related success.

“I don’t paint because I want someone to buy it or not. I paint from a very deep hole in my heart,” she said. The same goes for her subjects that can have their own social and political dimension, which she depicts in poetic form, absent of categoric messaging.

“I care a lot about the subject, and it was an honor for me to do my first Israeli show in a Palestinian art center, but the paintings—I just want them to be free from all of it,” said Herbelin. And though she still keeps her studio in Tel Aviv, and paints often in the desert, Herbelin came to France to gain distance from the political tension in her native country.

Upon arrival in Paris in 2011 for her studies at the Ecole nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris (ENSBA), she was “was very happy to not paint in such a political environment … and play with art,” but admitted that she also “felt guilty, and still [does] sometimes.”

At the same time, some of her subjects, like the nomadic Bedouin community, or her Eritrean neighbors who told her of their marginalization in Israeli society, are charged with an inherent political complexity, which transfers to the painting. Herbelin instinctively seeks these paradoxes. “Everybody who is coming from Israel and this territory… feels the contradictions all the time, like in the Bible … It’s not black and white.”

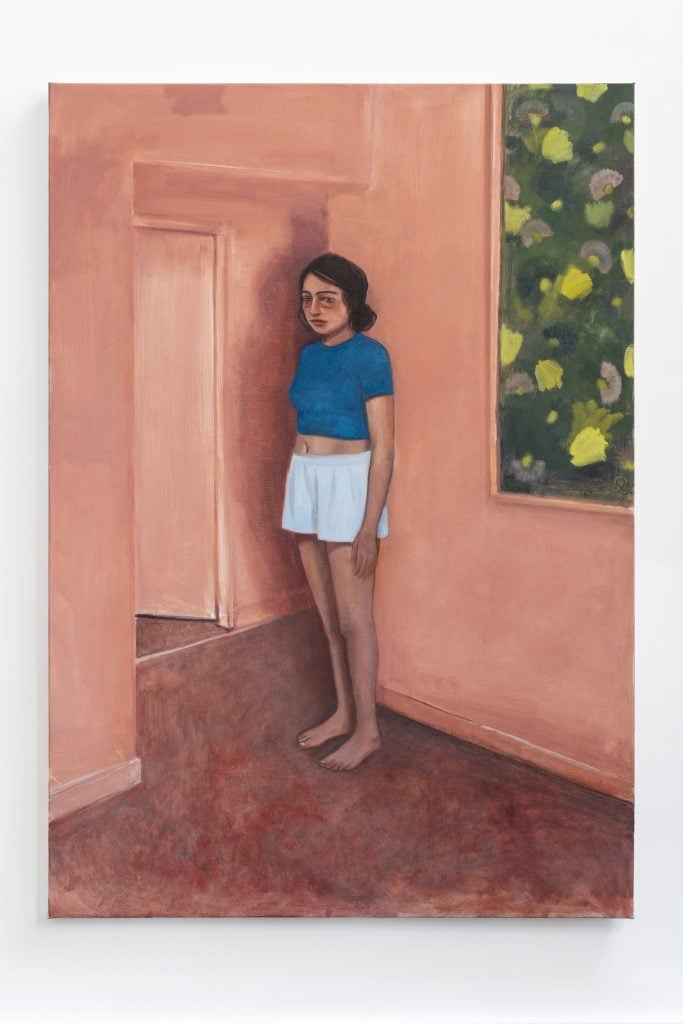

Nathanaëlle Herbelin, Zhenia (2021). Courtesy FRAC Champagne Collection.

Meanwhile, having made much of her life in Paris, living as a part-time expat with regular periods of time spent home in Israel, comes with strings. Herbelin feels “excluded” for now, from the Israeli art scene, where she doesn’t spend enough time, and “longing is a thing that stays,” she said. “It’s getting harder all the time.”

Growing up in Zoran, a small village in central Israel, Herberlin didn’t have models of professional artists, other than her “hard-core” Russian art teachers. She assumed she’d teach art, particularly to special needs children. Once at ENSBA in Paris “I was hallucinating,” she said, when “I saw that my teachers are just teachers for fun or something.”

But Herbelin was supported by her family, a mother (businesswoman), father (an engineer), “arty” grandmother in France, and siblings also now in the arts, who all recognized her tireless work ethic. “Psychologically, I need to paint all the time, everywhere… It’s completely neurotic,” she said, adding she plans to continue to paint in the studio with her soon-to-be-born child.

In Paris, Herbelin matured away from her early technically proficient, academic style. “The French spoke a lot about ‘sensitive painting.’ I started to explore this … to look at Morandi,” she said. “Less was all the time more, and I started to know where I was going. Silence was interesting to me in painting … I would never make—especially at the time—a painting that would bark.”

Her works also “slowly and happily” dialogue with abstraction. “I have all my life” to make an abstract painting, she mused.

A key turning point in her visibility came from a 2021 solo show at Jousse Entreprise, when artists and a “diverse audience that isn’t necessarily used to coming to art exhibits,” showed up at the sold-out show, said the gallery’s Nasla, who confirmed works currently cost under $52,000, and that there is not yet an active secondary market.

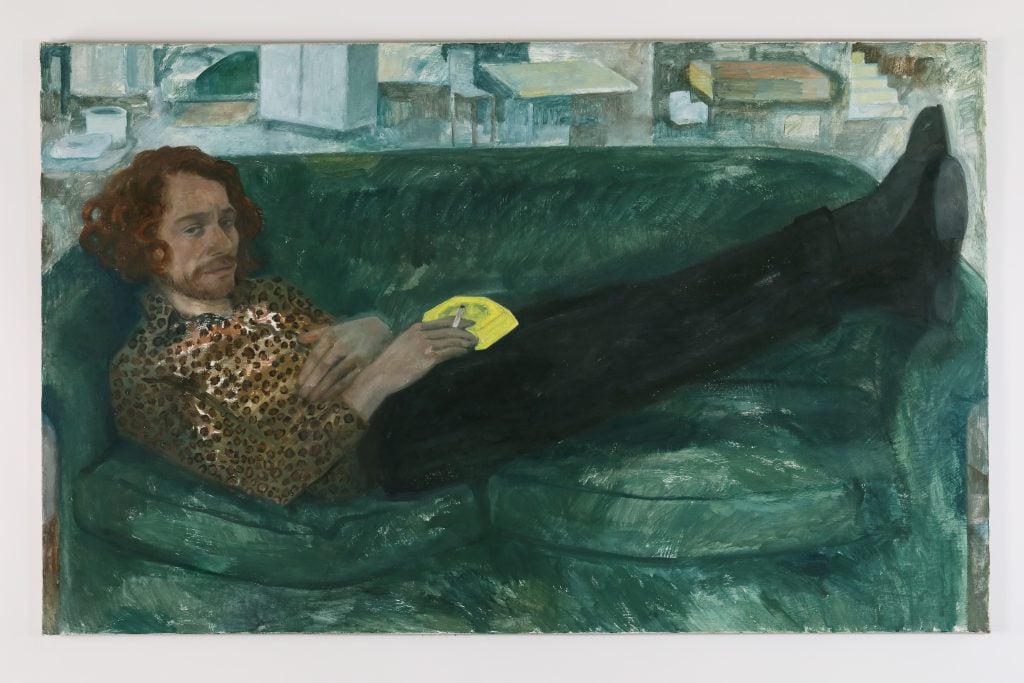

Nathanaëlle Herbelin, Augustin (2022). Courtesy the artist and Jousse Entreprise, Paris.

While figurative painting is trending, Herbelin’s work stands out, striking a chord among viewers with less of a penchant for the genre. In many contemporary works of “the super-fashionable Parisian scene, there’s an immediate representation of something we recognize … in a very pop – y way,” said Noam Alon, who curated her duo show with artist Anne-Charlotte Finel, Veillée d’armes at Paris + by Art Basel. “But in Nathanëlle there is a simplicity that is not trying to create any kind of impression.”

“Her work is very rich. You pull one thread, and others follow,” enthused Anne Dary, curator and former director of the Musée des beaux-arts de Rennes. Dary is particularly proud of acquiring Herbelin’s Gabriel Garcia Marquez, 100 ans de solitdue, Paris, éditions du Seuil, 1968, page 49 (2017) for the museum about 5 years ago, a strong example of the artist’s interest in literature.

Dary included Herbelin in a 2023 itinerant exhibition she curated about “young figuration in France,” to start at the Musée des Sables d’Olonnes. She “is part of an informal group of young artists who stick together and support each other,” added Dary. They include Cecilia Granara (born in Saudi Arabia), Elené Shatberashvili (born in Georgia), Simon Martin (born in France) and others. Many were exhibited at Jousse Entreprise in an influential 2019 exhibit curated by Anaël Pigeat and Sophie Vigourous, which continued at the Fondation d’entreprise Pernod Ricard earlier this year.

This month, Herbelin and French artist Jean Claracq (born 1991) were also invited to curate an exhibition at Mendes Wood DM’s Brussels space, “because we recognize their valuable contributions to the Parisian contemporary art scene, and particularly their support for young artists,” a representative for the gallery said.

Now Herbelin is facing the happy problem of learning to say no, but insists on using her success to champion fellow artists in her circle, because “artists did it for me, when I needed help,” she said. “I just don’t want artists to feel they’re in an individual kind of path – I can’t stand it. I come from Israel—kibbutz style—and I just need everybody to work together, because it’s more fun, and less lonely.”