Art History

Why Is Murano Glass So Special (and Expensive)? Experts Give Us 8 Reasons

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Venetian craft became a global brand. Here's how that happened.

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Venetian craft became a global brand. Here's how that happened.

Menachem Wecker

The Getty shop justifies a colorful goblet’s $45 price tag by noting that it hails from the Venetian island of Murano, “famous for its highly prized, collectible glass.” Walmart writes that a $57.95 plum figurine embodies Murano’s “richness of color, originality, and unparalleled craftsmanship.”

Stunning yet pricey, Murano glass is frequently hawked this way: as the epitome of style and quality. But what, exactly, makes it so special? And how did it become an international brand name with such strong resonance in the United States?

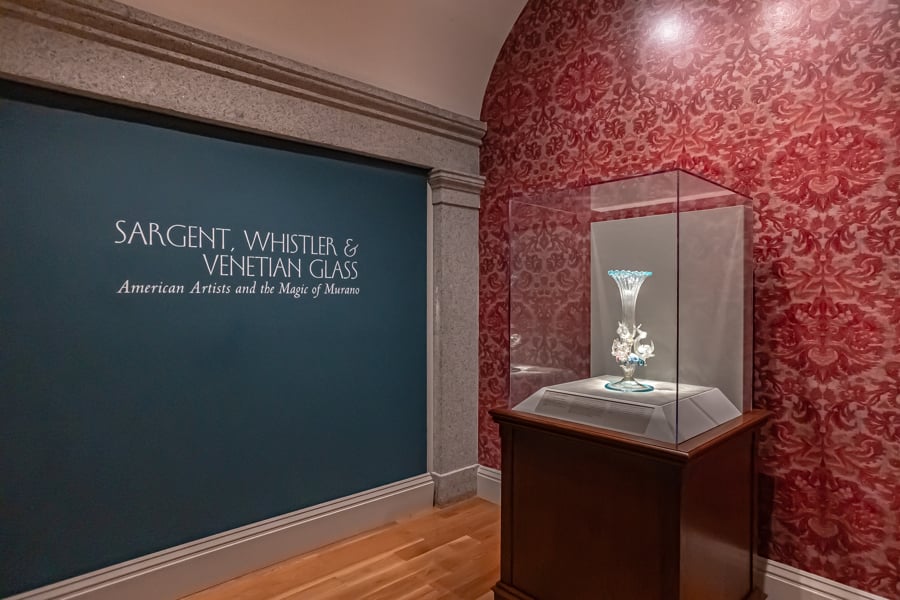

These questions are at the heart of “Sargent, Whistler, and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C. (The exhibition is on view until May 8, when it travels to Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum of American Art.)

We asked the exhibition’s curator Alex Mann, now chief curator of Savannah’s Telfair Museums, and other experts to give us the lowdown on this highly prized material. Here’s why it has captivated audiences around the globe—and commanded such high prices—for centuries.

Manufactured by Compagnia di Venezia e Murano (CVM), Vase with Dolphins and Flowers (ca. 1880s–1890). Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Murano glass comes in many shapes and sizes, from relatively simple forms to impossibly delicate and complex constructions. It is unified by one common trait, according to Mann: excellence. Murano craftspeople shared “an ambition to be at the very top of their field or skill set,” he told Artnet News.

The 150 objects in the SAAM show, which spans 1860 to 1915, reveal what American collectors considered excellent, which involved complexity, color variety, lightness, and delicacy. (“If you define ‘excellence’ as durability, Murano glass fails,” Mann quipped.)

Murano’s long and rich glassmaking history—which dates back to the Renaissance on Murano and to antiquity when Italy was part of the Roman Empire—contributes to its uniqueness. The high-quality materials used in the region “resulted in the creation of some of the most elegantly designed and expertly made glass found throughout Western Europe,” said Diane Wright, senior curator of glass and contemporary craft at the Toledo Museum of Art. From the moment it was produced, she said, “this glass was sold and admired around the world.”

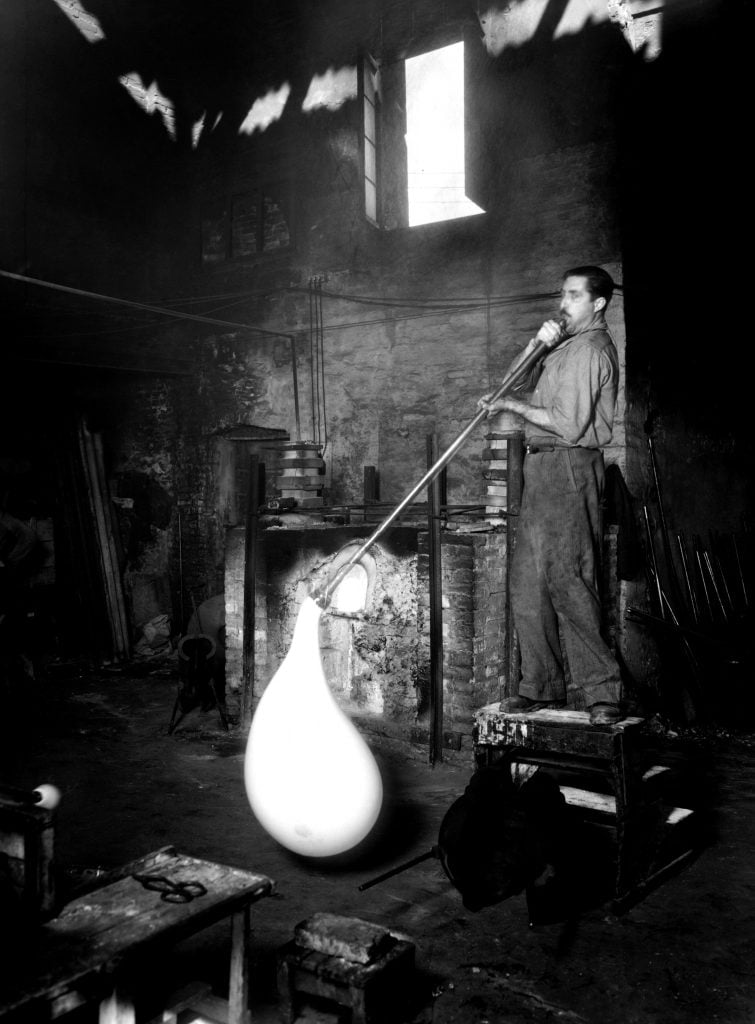

Processing of glass in Murano, 1955. (Photo by: Touring Club Italiano/Marka/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

An otherworldly aura surrounds Murano. The story of Italian glass production was compelling and mysterious to American buyers, since glassmaking wasn’t (and still isn’t) intuitive. “Unlike painting or drawing, it is complex in terms of its material and involves equipment and skills that need a little bit of extra explanation,” Mann noted. Even when one knows how glass is made, many still see “a little bit of magic or sorcery that’s happening.”

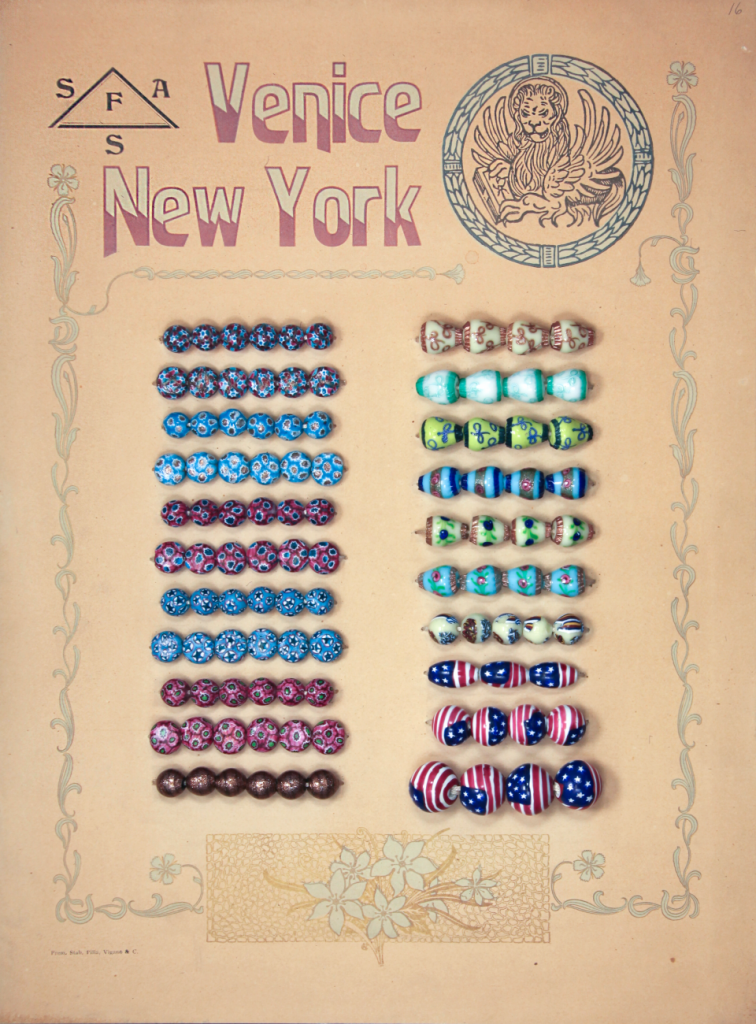

Venetian glass beads uncovered in Alaska. Photo: Lester Ross. Courtesy of Robin Mills.

Fine-art, blown Murano glass sucked up a lot of the island’s reputation among Grand Tour visitors, but Murano’s glass beads must not be ignored. They were Venice’s bread and butter when one-off luxury glass revenue ebbed and flowed. More than half of Murano’s glass workers made beads, according to Mann. (Beads, mosaics, and blown glass are distinct processes, produced in different furnaces and factories.)

Groundbreaking research published last year identified Venetian glass beads in Alaska decades prior to Christopher Columbus’s voyage, making them the earliest European objects discovered on the continent. But beneath their shiny veneer, Murano beads have a dark history. Scholars refer to them as “trade beads,” since they were exchanged, often in large quantities, in Africa, India, and China, and with Native Americans in North America. Beads were traded for enslaved people, gold, and gems in transactions that were often exploitative for those on the other end of the deal (not to mention those traded).

Attributed to Societa Veneziana per l’industria delle Conterie & Stephen A. Frost & Son, Sample Card with Millefiori and Flag Beads (late 19th century–1904). Courtesy of Illinois State Museum.

Although men worked in the Murano factories amid the heat and flames, women were very involved in making the beads. “Beadmaking was a multi-step process, in which some steps occurred outside of factory settings, given that some tasks—sorting and stringing—could be performed in domestic settings,” Mann said. Venice’s economy benefited from the ability of bead production to incorporate a wider workforce, which provided secondary income to individual households.

John Singer Sargent, A Venetian Woman (1882). Cincinnati Art Museum. Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

American tourists began to notice Murano in the 1860s, when Italy became independent and its glass furnaces returned to full swing. Artists were among the island’s most enthusiastic early visitors. John Singer Sargent, James Abbott McNeill Whistler, and others shared their Venetian experiences, including of glassmaking, with the American public, and 19th-century Americans appreciated Murano glass at their homes, offices, and world fairs.

The objects also began popping up in art. Once Mann had trained his eyes, he almost couldn’t unsee glass in paintings, particularly in interior genre scenes. Many viewers have likely seen paintings by Whistler and Sargent that portray glass without realizing it; one can return to them and take a page from “Where’s Waldo?”

Today, many successful American artists reflect Murano influence in their techniques and styles (think: Dale Chihuly, Josiah McElheny, Fred Wilson). “This speaks to the interconnectedness of artistic movements, as well as the importance of global experiences to foster creativity,” Wright said.

Installation photography of “Sargent, Whistler and Venetian Glass: American Artists and the Magic of Murano,” 2021. Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum; Photos by Albert Ting.

In recent decades, Murano glass has fallen out of fashion. Since the 1920s and ’30s, collectors and museums alike favored more streamlined, traditionally modernist forms over ornate glass. “In many institutions, the pieces are no longer on view,” Mann said. “In a way, we were discovering or cataloging and giving new attention to objects that probably had not been on view at those institutions—including the Smithsonian—for half a century or more.”

Vittorio Zanetti, Fish and Eel Vase (ca. 1890). Courtesy of Smithsonian American Art Museum.

In the late 19th century, the idea of art for art’s sake was strong—and this concept also extended to Murano glass. The Fish and Eel Vase (c. 1890) included in SAAM’s show is a sterling example of useless beauty. Despite the name, “it’s surprisingly not utilitarian,” Mann said. The complex object—which SAAM’s website notes has no historical precedent—seems to defy gravity. “There was definitely a premium placed on delicacy, fragility, and complexity that was promoting a specific set of ideals that are in line with the aesthetic movement,” Mann said.

Many Murano pieces are so fragile that quite a few have been lost to history. Stanford University’s collection was “tremendously injured” in the great 1906 earthquake, Mann noted, after which the Salviati company of Murano glassmakers donated objects to the university’s museum to replace those that were lost.

John Singer Sargent, Venetian Glassworkers (ca. 1880–82). Courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Mann sees a “web of lines” that spans the globe and stretches back in time, connecting contemporary glass collectors to late 19th and early 20th century glassmakers. Many pieces of that era replicated forms popular in the Renaissance or ancient Rome, so the objects, too, connect to the distant past. One example in the show is a copy of the Renaissance “Campanile” beaker (c. 1912), which was discovered broken in St. Mark’s Square in Venice after the bell tower (campanile) fell in 1902.

The history of Murano glass inspires Mann to consider objects in his personal collection, including those he inherited from his grandmother, and to ask questions about their layered journeys. “Each piece of glass,” he said, “is a starting point for telling stories.”