When designer Alexander Díaz Andersson moved from Sweden to Mexico 14 years ago, he had only planned to live there temporarily. Fast forward to today: Díaz Andersson is the founder and creative director of ATRA, a furniture studio based in Mexico City, his adopted home. Through the years, he has become an integral part of the country’s emergence on the global design scene, his pieces combining the minimalism of Swedish design with a maximalist Mexican aesthetic.

Díaz Andersson refers to this as the “techno” element of his practice—something he shares with British designer Julian Mayor, who typically works with sheet metal. Mayor’s trademark is merging a highly technical, computer-based design process with hands-on welding and craft, and his pieces have a certain flashiness. While Mayor has primarily worked in the U.K. and the U.S., a recent visit to Mexico City inspired him in a new way.

Speaking for the first time, the designers shared with Artnet News their mutual admiration for traditional craftsmanship, how Mexico inspired their recent projects in collaboration with Maestro Dobel Tequila—for Mayor, an eight-foot-long bar at Art Basel Miami Beach in 2019; for Díaz Andersson, a Maestro Dobel Artpothecary furniture project at this year’s Design Miami, where ATRA was awarded “best in show”—and “the sense of soul,” Díaz Andersson says, that infuses both their work.

Julian Mayor and Alexander Díaz Andersson.

Courtesy of the designers.

What is the story behind each of your decisions to pursue a creative career?

Julian Mayor (J.M.): I’ve always enjoyed creating stuff with my hands. My dad was a woodworking teacher. I’ve got two brothers and we spent time making things [with him] as kids, like skateboards and ramps.

Alexander Díaz Andersson (A.D.A.): I was going to study finance, but my girlfriend [at the time] thought it was a bad idea. She really pushed me into studying design. My grandparents were in the furniture industry, my mother was in the furniture industry, and then my family started doing consulting for IKEA in the U.S. So when I came back from university, it became very easy for me to integrate my studies into [this work].

I never thought I was going to become a designer, to be honest. It took me 10 years, but I got kind of obsessed with woodworking, metals, and how materials work. And all of a sudden, 10 years passed. It became a real career at the end.

What do you consider to be the most urgent or interesting aspects of design at this moment in time, and how do you address them in your work?

J.M.: I’ve always been interested in the rational, geometric, scientific-based approach to creating an object. Computers are something that I use as a digital sketchpad and jump-off point to creating an object.

But then also, for me, the craft of making things by hand is very important. So my work is [those] two contrasting elements.

And I see that in [your] work, Alexander. I really like the detail and the patina of [it].

Mayor’s mirrored-steel Parallax chair. Photo: Armel Soyer.

A.D.A.: So I think I share that a bit with [you]—this combination of 3D design and engineering with traditional methods and craftsmanship. Even though you have this more mathematical approach, you still have…I don’t know if we [can] call it imperfection, but the soul of human hands being implemented in the product.

J.M.: The element of chance comes into it when you make things by hand.

A.D.A.: I think that also, most urgent—apart from the designer aspect—[is] this sense of sustainability. That’s something we have to address at the end of day. I’m using wood; I’m using stone; I’m using a lot of things. And my things are not very efficient. But I see [a] quality product or object that’s meant to be passed down [as] another [type] of sustainability—something that lasts for a long, long time.

In my house in Sweden, I grew up with my grandmother’s furniture, and her grandmother’s. It’s this idea that something can be acquired—the lives of different families, lifestyles, and experiences.

J.M.: I think making things sustainable is difficult, and it is a pressing question. I don’t make many things, and all the things I do make, I make by hand—[which] obviously limits the amount of pieces I can make.

A.D.A.: We’re at a point right now where I feel like we live in a very archaic system. So many things are happening—technology is growing exponentially; you have this whole blockchain thing going on; [everything] with the metaverse. So inside of this universe, [as] we’re becoming more technological, I think that the work that we’re doing is becoming scarcer. There are much less artisans. There are easier ways of making money. I think these objects and this kind of work [are] going to become even scarcer in the future.

We have this great opportunity to bring these works [into] that realm. I think that’s the way of becoming relevant, but also finding more sustainable models to create and build and grow.

One of Díaz Andersson’s ATRA designs, the Oberon Sofa Mach II. Courtesy of ATRA.

What do you believe is the most imperative factor in maintaining a career in the arts?

J.M.: I think maintaining a passion for your work. That’s something that I do have.

And then building an audience for your work is very important. Because sometimes when you’re making pieces, you’re not just making pieces for yourself. It’s like a collective dream in a way: you’re trying to create something that people will respond to.

A.D.A.: It took me a long time to acquire a language that I felt that belonged to me. It was a lot of work in a bubble for many years before getting out there. And I was so focused on woodworking, and I worked in a workshop for so many years, that when I [tried to come] up with something that was attractive, [there] was a big disconnect [between that and] what people wanted or were looking for.

J.M.: I feel like [that’s something] we have in common. You do have a strong design language, and it’s very clear. My experience of your work was that it’s sort of sophisticated and elegant, but it also has a touch of punk rock in there.

My work isn’t quite as elegant; maybe it’s a bit more punk rock–y. But you certainly have that element in your work, Alexander—that sort of rule-breaking defiance.

A.D.A.: It’s super-[funny] that you say that, because when something is too polished or too perfect, like I need to give it [grit and] character.

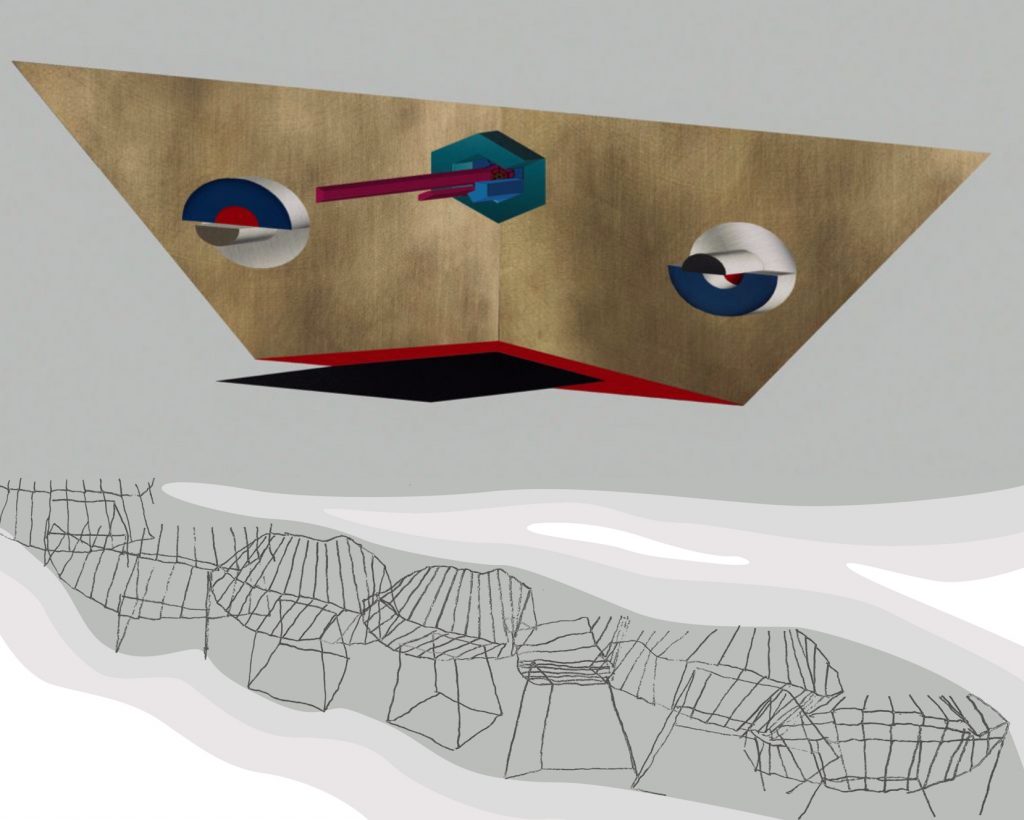

Mayor designed a bar with Maestro Dobel, inspired by Mexican agave. Courtesy of the designer.

What drew each of you to Mexico? Why is it a fruitful setting for your artistic production?

J.M.: I recently collaborated with Dobel. My inspiration for the project was agave—I designed a sculpture based on [the] plant, and it progressed into a bar. I went to Mexico City to get the vibe, and I loved it.

I stayed with a friend who lives there. We [did] the Dobel Tequila experience. It was a kind of virtual tasting session, but there [were] also VR goggles and stuff. It was bonkers. It was great.

It really opened my eyes.

A.D.A.: For me, the collaboration [with Dobel for Design Miami] was more creating this dialogue between Dobel, [ATRA] design, and the food [from chef Jorge Vallejo of Mexico City’s Quintonil].

I [came] to Mexico 14 years ago, when my family moved [here] from Sweden. And I kind of got stuck here. I wasn’t planning on staying—it [just] kind of happened.

It’s a very generous country. And it’s very fertile. Everything is new. When I started in design, there were not many players on the scene. Everyone was buying the Italian designer, or German, or Swiss, or Swedish, or Danish, but they certainly were not buying Mexican designs. It was like 10 years being there in a non-existing industry.

What was like a desert is today becoming a [global] design reference. We’re still very far away geographically from [other] design [hubs], but I feel like the Internet and social media makes [us] closer every day. Even so, there is a very strong value proposition coming from Mexico—a very distinct DNA, and it’s very cool to be a part of that.

Maestro Dobel Artpothecary’s The Fruit Chemist at Design Miami, with furnishings by ATRA. Courtesy of Maestro Dobel.