Pop Culture

From ‘Parasite’ to ‘Titanic’: 10 Iconic Art-Filled Films to Watch Over the Holidays

Which artists and artworks have made surprising and memorable cameos on the big screen?

Which artists and artworks have made surprising and memorable cameos on the big screen?

Eileen Kinsella

Think art is just a prop in movies? Think again. Major masterpieces often making unexpected appearances on the big screen and can even be integral to the plot. From the haunting childlike drawings in Parasite to Seurat’s serene masterpiece in Ferris Bueller’s Day Off, these carefully chosen works of art add layers of meaning, symbolism, and visual flair to our favorite films.

With the holidays approaching—and plenty of time to stream and relax—we’ve rounded up 10 films filled with art for you to enjoy. Happy holidays and happy viewing!

Song Kang-ho, who plays the destitute Mr. Kim, holding the suseok in Parasite. Photo ©2019 CJ ENM CORPORATION, BARUNSON.

In a particularly humorous scene from this hit Oscar-winning film, a young woman named Ki-jung (Park So-dam) poses as an art therapist to land a lucrative job in the household of a wealthy Korean family. The childlike drawings were made by up-and-coming Korean artist Zibezi. After a friend recommended his artwork to Parasite director Bong Joon-ho, it sent his art career soaring.

Ray Liotta, Robert De Niro, Paul Sorvino, and Joe Pesci pose for a publicity portrait for Goodfellas (1990). Photo: Warner Brothers/Getty Images.

In the beloved gangster movie about real-life mobster-turned-informant Henry Hill (Ray Liotta), one of the most famous scenes takes place in a kitchen where director Martin Scorsese’s real life mother, Catherine, plays the role of mother of wise-cracking Tommy De Vito (Joe Pesci), and she’s showing off one of her paintings.

Many assumed the painting is fictitious, but in fact, it was based on a photograph by Adam Woolfitt from the November 1978 issue of National Geographic, where it was included in a feature on the River Shannon in Ireland. The hilarious ensuing mobster art critique of the painting is one of the film’s funniest moments.

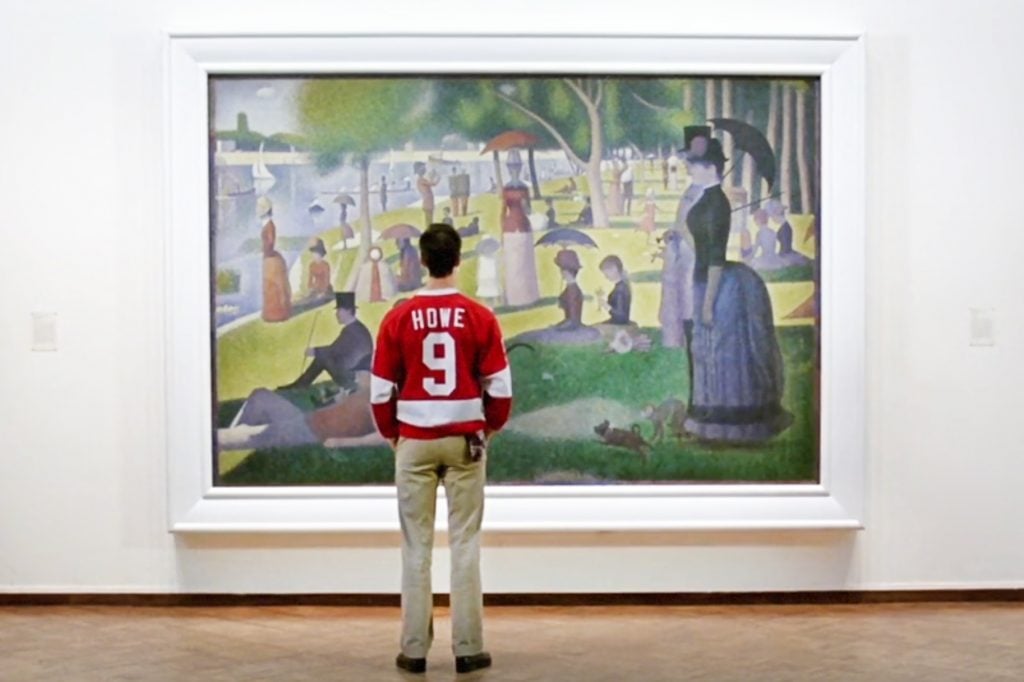

A still from Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986) set in the Art Institute of Chicago. Courtesy of Paramount Pictures.

Amid a full-day of school hooky hijinks in the Windy City, the film’s three main characters, Ferris Bueller (Matthew Broderick), Sloane Petersen (Mia Sara) and Cameron Frye (Alan Ruck), make a stop at the city’s beloved, masterpiece-filled Art Institute of Chicago. As The Smiths’ famous song “Please Let Me Get What I Want,” soars in the background, the group takes in the masterpieces, including a beautiful close-up of Georges Seurat’s iconic Pointillist masterpiece A Sunday on La Grande Jatte (1884).

Kate Winslet in Titanic (1997), holding a replica of Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). Photo: Screen grab.

In a famous but deleted scene towards the beginning of James Cameron’s hit film, Rose’s (Kate Winslet) maids carry her collection of modern art into the luxury suite. “Who’s the artist?” one of the maids asks. “Something Picasso,” Rose answers. The painting in question is Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), painted five years before the Titanic set sail from Southampton. Also on board are reproductions of L’Étoile (The Star) (1878) by Edgar Degas and a canvas from Claude Monet’s series of “Water Lilies.” Rose’s fiancé Cal (Billy Zane) disdainfully dismisses the paintings as a “waste of money” and opines forcefully that this Picasso guy “will not amount to a thing.”

Zawe Ashton and Jake Gyllenhaal in Velvet Buzzsaw (2019). Photo courtesy Netflix.

In this surreal art world satire, where people become victims of violence at the hands of the artworks themselves, critic Morf Vandewalt (Jake Gyllenhaal) asks a cataloguer named Gita (Nitya Vidyasagar): “That’s a Freud?” a reference to famous portrait painter Lucian Freud, whose works have sold for as much as $86 million at auction. Vanderwalt is looking at a large canvas in the corner of the room, a picture of a nude man, staring directly at the viewer. Gita responds drolly: “It’s been in a crate since ’92, and it’s going back in one.”

Nicole Kidman in Eyes Wide Shut (1999). A painting by Christiane Kubrick hangs in the background. Photo: Screen grab.

Stanley Kubrick’s much-hyped 1999 film featuring Tom Cruise and Nicole Kidman as married couple Bill and Alice featured a healthy sampling of works by Christiane Susanne Harlan, a German-born painter who met Kubrick on the set of 1957 antiwar film Paths of Glory. They eventually married.

She started painting after studying art in California, building a successful career with exhibitions in Rome, London, and New York. Christiane’s most prominently featured work in Eyes Wide Shut is titled Seedbox Theatre, a long landscape depicting a garden with graphically rendered flowers, which hangs in the couple’s dining room.

Gary Oldman and Keanu Reeves in Bram Stoker’s Dracula (1992). Photo: American Zoetrope © 1992.

Francis Ford Coppola’s 1992 cinematic take on this well-trodden subject matter features Keanu Reeves as young British solicitor Jonathan Harker. In one of the movie’s foreshadowing scenes, Harker is seated at a dining room table inside a Transylvanian castle, speaking with the lord of the castle, Count Dracula (Gary Oldman), who is his new client.

While dining, Harker points out a nearby portrait depicting a saintly, longhaired, bearded man, and notes a family resemblance to his host. Unbeknownst to Harker, the model in the painting is in fact a young Vlad Dracula, in his pre-vampire state. The artwork is immediately recognizable as a replica of German Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer’s Self-Portrait at Twenty-Eight. The original painting, completed in the year 1500 just before the artist’s 29th birthday, is regarded as Dürer’s most significant artwork.

Amy Adams in Nocturnal Animals (2016). Photo: Atlaspix / Alamy Stock Photo.

In Tom Ford’s award-winning 2016 psychological thriller Nocturnal Animals, gallery owner Susan Morrow (Amy Adams) receives the manuscript of a novel written by her estranged ex-husband Tony (Jake Gyllenhaal). The book follows a man seeking revenge.

Not surprisingly, Susan constantly finds herself surrounded by art. Some works, like Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog or Alexander Calder’s Snow Flurry, were specifically written into the screenplay by screenwriter Austin Wright to reflect the character’s emotions. Perhaps most telling is a a black-and-white painting with Christopher Wool-esque stacked letters spelling “REVENGE,” in front of which Susan pauses.

Donatas Banionis in Solaris (1972). Photo: Mubi.

The sci-film directed by Andrei Tarkovsky revolves around a space station orbiting the fictional planet Solaris, where a scientific mission has stalled because the barebones crew of three scientists has fallen into emotional crises. Psychologist Kris Kelvin (Banionis) travels to the station to evaluate the situation, only to encounter the same mysterious crisis.

Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s The Hunters in Snow (1565) depicts a group of figures returning from a hunt, with a wintry village vista unfolding in front of them. While the character Hari sits alone in the space station’s library, gazing at the painting with cigarette in hand, the camera pans slowly over it.

The everyday landscape joins others in Bruegel’s painting cycle, “The Months,” works of which depict harvesters (The Hay Harvest) and cattle herders (The Return of the Herd), and which were also recreated for Solaris‘s library.

But it is Hunters that Tarkovsky draws viewer attention to. The snow-white setting further recalls an earlier scene in the film when Kris plays an old home video for Hari, in which a young Kris is seen running in the snow with his father, while his mother stands at a distance smoking and clutching a small dog. “I don’t know myself at all,” Hari responds. “I don’t remember.”

Catherine Keener in Synecdoche, New York (2008). Photo: Cinematic / Alamy Stock Photo.

Screenwriter Charlie Kaufman, famous for penning Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, made his directorial debut in 2008 with Synecdoche, New York which follows a marital conflict between two artists living in the quiet upstate town of Schenectady. Neurotic theater director Caden Cotard (Philip Seymour Hoffman) sees his life crumble when his wife Adele (Catherine Keener), who paints miniature paintings, takes off for Germany with their daughter Olive.

Each tiny detail and narrative in the film relates to the film’s overarching themes, and naturally to Adele’s artwork. The works, which are created by artist Alex Kanevsky, often depict Adele’s lovers in a blurry, Impressionist style. This reference and echoes a key part of the plot: that nothing is what it seems, and that we can never truly know another person beyond our superficial assumptions of them.