Opinion

The 100 Works of Art That Defined the Decade, Ranked: Part 2

In the second installment of a four-part series, our critic reveals his picks—number 75 through number 51—of the key art of the 2010s.

In the second installment of a four-part series, our critic reveals his picks—number 75 through number 51—of the key art of the 2010s.

Ben Davis

This is the second part of a series looking at the art of the 2010s. The other parts are here, here, and here.

Pierre Huyghe’s, Untilled (Liegender Frauenakt) (2015). Courtesy of MoMA.

Originally created for the immensely well-liked Documenta 13 in 2012, and becoming one of the images most associated with it, the French artist’s bee-headed sculpture has had a fertile afterlife.

Installation view of Jacob Hashimoto, Gas Giant at MOCA Pacific Design Center. Photo by Brian Forrest, courtesy of the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.

“Gas Giant” is actually the name of a trio of installations by Hashimoto, made between 2012 and 2013, making spectacular use of Japanese kite-making techniques. The installation is memorably delightful, a fresh kind of kinetic abstraction.

Fairgoers take pictures of Maurizio Cattelan’s Comedian, for sale from Perrotin at Art Basel Miami Beach. Photo by Sarah Cascone.

I knew that a work by Cattelan would be on this list, because his sour, media-smart humor has proved a major influence in the 2010s (despite his purported retirement). I was thinking it would be America (2018), his gold toilet at the Guggenheim. But I give in: The self-annihilating irony of the $120,000 banana at Art Basel Miami Beach is a one-liner, but it is a one-liner that people will be telling each other for a long time.

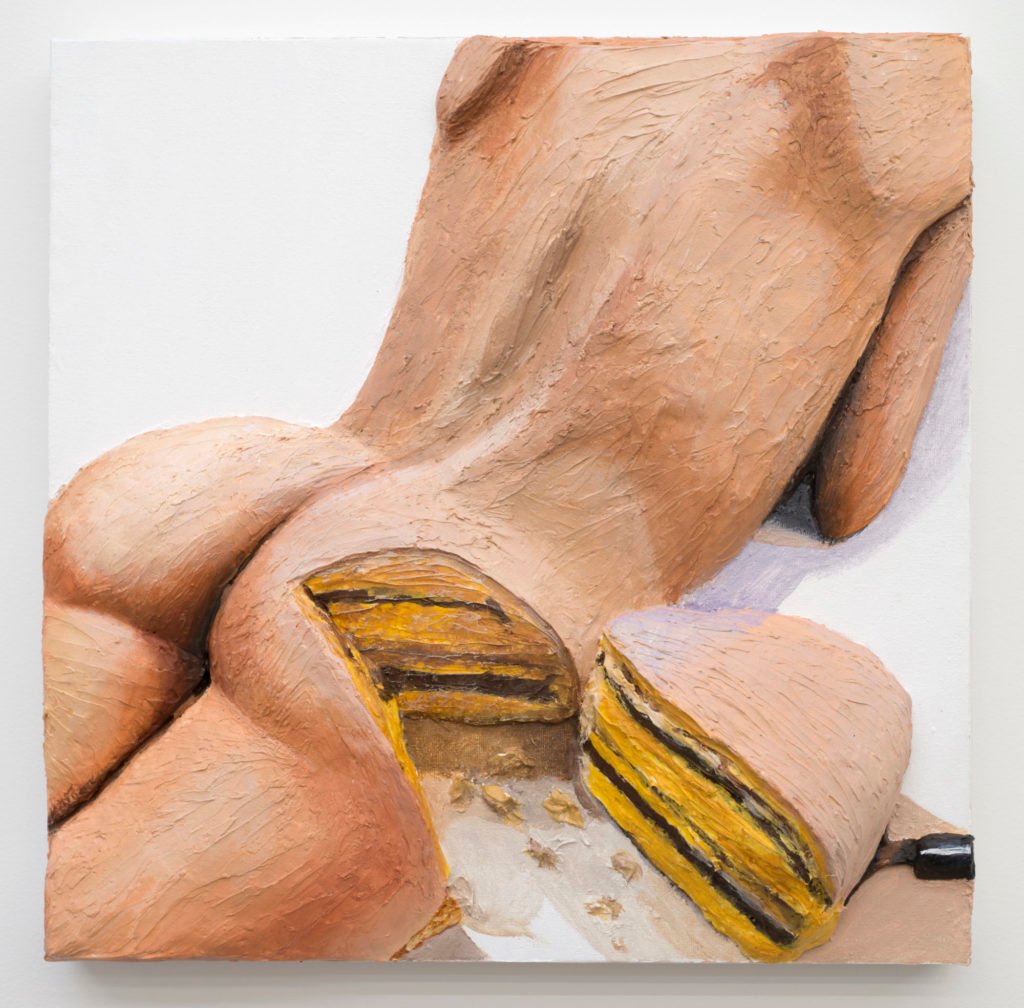

Gina Beavers, Cake (2015). Courtesy the artist

Just a tremendously weird, resonant painting, riffing on different kinds of appetites, and also giving a double meaning to Beavers’s thick, frosting-like surface. Try forgetting the image.

Michael Pinsky, Pollution Pods at the 74th United Nations General Assembly in partnership with the World Health Organization. Photo by David Buckland of Cape Farewell.

The product of a four-year Climart initiative to see if art can change minds about environmental issues and now tailing environmental summits around the world, Pinsky’s pod-environments are designed to give those who pass through them a literal whiff of the air quality in various cities around the world: London, Beijing, New Delhi, São Paolo, and Tautra, Norway (where it began its life). It takes the strengths of “immersive” installation art and puts them to agitational ends.

Titus Kaphar, Shifting the Gaze (2017). Photo: Jack Shainman Gallery, courtesy of the Brooklyn Museum.

Kind of an anti-painting painting, and symbolic of a much larger conversation: Working onstage during a 2017 TED Talk seen by about 1.5 million people, Kaphar displayed a copy of a 17th-century Dutch portrait by Frans Hals, Family Group in a Landscape (ca. 1645-48), explicating its compositional language and gradually painting over the principal figures to leave only the black figure otherwise overlooked in the background visible.

Dancers performing MEƎM 4 Miami: A Story Ballet About The Internet by Ryan McNamara. Image courtesy of the artist.

The winner of Performa 2013’s Malcolm McLaren Award, McNamara’s inventive dance/immersive performance featured viewers in movable chairs, being shuttled from one dance tableaux to the next, a groovy attempt to use the resources of live-ness to reflect on the gibbering, dispersive, but mesmerizing landscape of the internet.

“It took me 30 years to find a form that allowed me to free my images from the wall, from the matt and the frame,” the artist writes. Famed for her lyrical documentary images, Singh has this decade gone about rethinking the way she takes charge of the meaning of her archive, hitting upon the idea of these folding, handmade wooden frames, housing hundreds of images in temporary configurations as mini-“museums” of themes (one is on view in the MoMA’s Sixth Floor now). These can be reordered, opened up, or locked together to form labyrinths of images—encouraging a viewer to think of the photos as literal building blocks of meaning that exist in the world with you.

Kids art class. Image courtesy Immigrant Movement International.

With Creative Time and the Queens Museum, Bruguera founded the Immigrant Movement International as a test case of her idea of “Arte Útil,” pushing the “social practice” turn towards direct social-service provision to a limit. Her community service center for immigrants in Corona, Queens, has endured, and I gather it continues to evolve without her. (For the doubters, it’s worth checking out the Art21 documentary featuring painter Aliza Nisenbaum, talking about her experience teaching English through art to undocumented immigrants at the space.)

Josh Kline, FREEDOM (2015). Image: Benoit Pailley.

In contrast to the internet-themed Pop art of a decade ago, which was generally much more ironic and light-hearted, Kline’s work in general—and his Teletubby riot police specifically (seen at the New Museum Triennial in 2015)—provided the image of the new sensibility, in which our love of ironic junk came back to terrorize us.

Ian Cheng, Emissary Forks at Perfection (2015–16). Courtesy of MoMA.

Each chapter of Cheng’s “Emissaries” trilogy features a different animated digital landscape in which tiny AI-powered cartoon figures wander aimlessly as if they have been cut free from the background of some huger narrative. It has a slight retro-gaming aesthetic, but the entropic mystique has stuck around in my head, the retardataire feeling of its graphics starting to feel more and more meaningful as a symbol of being lost in a world of simulated memories and identities built around rootless mythologies.

Conflict Kitchen’s Schenley Plaza location, decorated for an Afghan menu in 2014. Photo by Ragesoss, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported license.

Serving dishes from countries in conflict with the United States, Conflict Kitchen was both a functional food stand in Pittsburgh and an informational kiosk promoting understanding and serving as a locus for debate with each new iteration. Rubin and Weleski, the artists behind it, are on to new things now, but the idea lives on as an example of art providing literal “food for thought.”

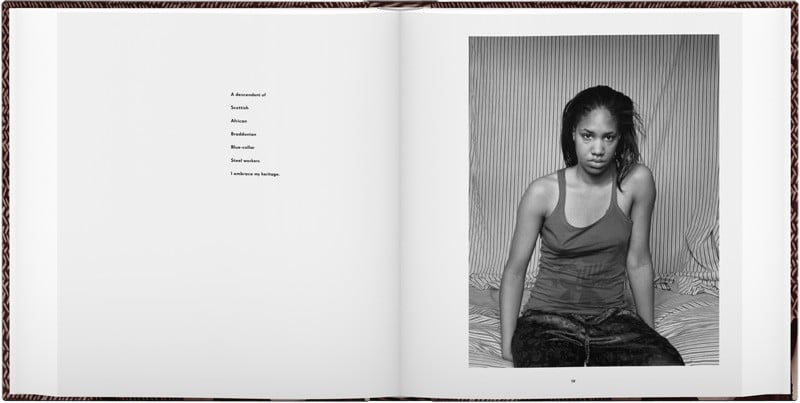

Spread from LaToya Ruby Frazier, The Notion of Family (2014). Image courtesy Aperture.

The story Frazier tells in the photos of The Notion of Family relates to the bleakness and abandonment of Braddock, Pennsylvania, the majority African American town where she grew up. The series is notable for the way that it combines the directness of black-and-white social documentary with a wrenchingly personal approach, returning again and again to the artist herself, her mother, and her grandmother. There’s just an overwhelming heaviness to The Notion of Family, everyone pinned still as if trapped.

A performer offers samples of Otobong Nkaga’s O8 Black Stone soap, produced in Athens for Documenta 14, outside the Neue Galerie in Kassel. Image: Ben Davis.

A work of wheels-within-wheels complexity, Carved to Flow is difficult to easily explain. It involved a soap-making workshop in Athens that became a project to have performers/vendors hawking Nkanga’s 08 Black Stone soap in Kassel, and then was finally meant to recycle those profits into the Carved to Flow Foundation in Akwa Ibom, Nigeria, which focuses on local ecologies. What I will say is that I think that Nkanga’s sensibility, where the discrete object is less important that the awareness about the networks of labor, business, and environmental impacts that flow into and out of it, is the emergent cultural mindset of the future.

Installation view of Anicka Yi, You Can Call Me F at the Kitchen. Image courtesy the artist and the Kitchen.

Yi’s installation of quarantine tent-like enclosures and ramshackle assemblages, incubating biological samples donated by some 100 other female-identifying artists, augured a whole new era of conceptually disorienting bio-art.

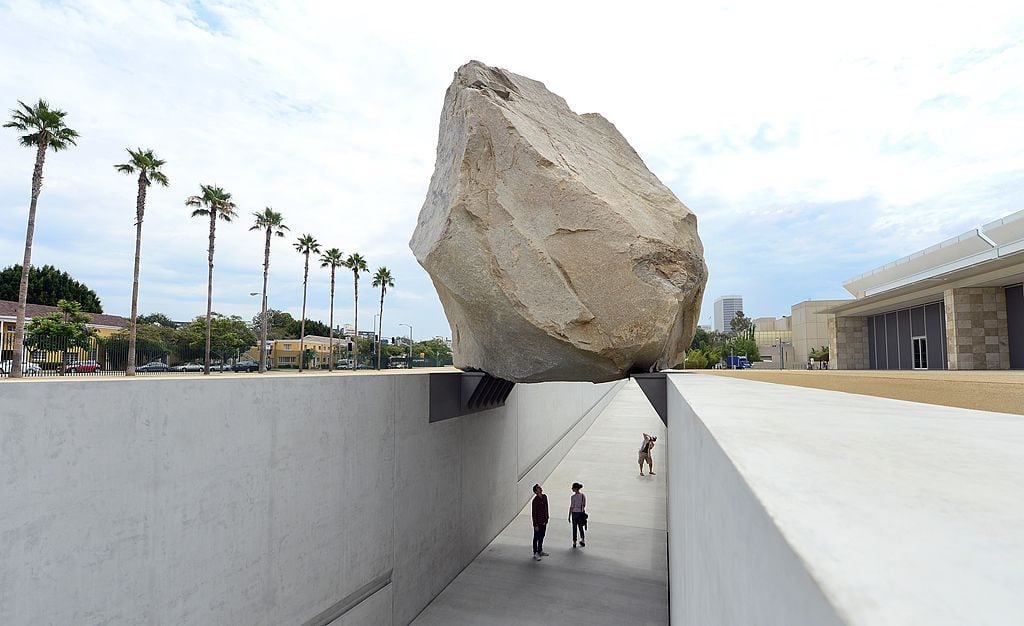

Michael Heizer, Levitated Mass (2012). Courtesy of Frederic J. Brown/AFP/Getty Images.

A completion of a certain symbolic journey for Land Art, with Heizer’s massive rock making the journey back to LACMA to loom—sublime nature tamed as an urban photo op. Its transit to the site became a sort of grand civic spectacle all on its own.

There’s something unforgettable about the gonzo grit of Iraqi artist Hiwa K’s performance This Lemon Tastes of Apple, which saw him walk into the thick of anti-corruption demonstrations on April 17, 2011 in Sulaimany, in the Kurdish region of Iraq, harmonica in hand playing an Ennio Morricone riff from Once Upon a Time in the West, as events rage around him. “The work,” writes the artist, “occurred within the protest and is not a work about the protest.”

Blas’s multi-pronged project, making aggregated data of facial features into eerie, melted wearable abstractions, is both unnerving as an image and a practical protest against the biases baked into facial recognition software (well, semi-practical).

Favianna Rodriguez, Migration is Beautiful (2013). Image courtesy Favianna Rodriguez.

Oakland-based Rodriguez, a printmaker, activist, and founder of CultureStrike, developed the image of the Monarch butterfly, which naturally migrates between Mexico and California, into a metaphor for immigrant solidarity in 2012, as a response to President Obama’s record-breaking deportations. It caught on. It’s still inspiring people in the age of Trump.

Jennifer Packer, Say Her Name (2017). Image courtesy Ben Davis.

As a slogan, “Say Her Name” was a response to media silence around cases of police brutality against black women and caught fire around the case of Sandra Bland, whose death in a Texas jail touched off a national outcry in 2015. Packer’s quietly vivid still life goes the other way, letting a painted funeral bouquet for Bland stand on its own, contemplated as an act of memorialization, withdrawing the case from the spectacular circulation of traumatic imagery.

Image from Jill Magid, The Proposal, blue diamond ring with inscription, “I am wholeheartedly yours.” Courtesy of the artist; LABOR RaebervonStenglin; and Galerie Untilthen.

Magid’s attempt to repatriate the archives of beloved Mexican architect Luis Barragán to Mexico, involving her successful quest to turn part of his ashes into a diamond engagement ring as a ploy (it’s too complex to explain here, and the New Yorker has done a better job of it anyway) sounds like something an artist would do in a movie. And, indeed, Magid has made a film of her quest, which is worth seeing on its own.

lauren woods, A Dallas Drinking Fountain Project (2015). Image courtesy the artist and Creative Capital.

woods has become a go-to figure for the counter-monument movement in the United States. She is on to much bigger things now, with her “American MONUMENT” project, an audio archive relating to police killings of black victims. Still, her “interventionist multimedia monument” at the old Dallas County Records building offered a deft new way to engage history in public space: marking the traces of a “White Only” sign lingering over a drinking fountain, it caused a video to activate about the history of Civil Rights struggle when you hit the button for water, an inconvenience that insists on the importance of not letting the past be washed away.

The name of the “96 Acres” project, founded by Gaspar, refers to the immense space taken up by the Cook County Jail in Chicago, effectively a city-within-a-city. It produced an acclaimed, years-long series of “community-engaged, site-responsive art,” among them Radioactive, which involved workshops with inmates on how to tell their story that became animated projections using the exterior walls of the jail as a screen. Gaspar’s impulse has inspired prison art-making initiatives elsewhere.

A still from the video for Khaled Hourani’s Picasso in Palestine (2011). Image courtesy the artist.

Artist and curator Khaled Hourani’s elaborate efforts to get Buste de Femme, a 1943 work by Picasso in the collection of the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven, to be seen at Ramallah’s International Academy of Art, has become, among other things, a widely seen documentary and a series of paintings. But really the entire project was consciously designed as a kind of critical gesture, a way to use the value of art and the difficulty of transporting it as a way to throw into relief the absurdities of life under occupation.

Danh Vo, We The People (detail) (2011–14). Photo: James Ewing. Image courtesy the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel.

Danh Vo’s idea for We The People—remaking the cladding of the Statue of Liberty, but disassembled, so that the plates become abstractions—is so elementally evocative and symbolically potent that you are amazed that it hasn’t been done before.