Art World

15 Minutes With a Price Database Power User: Fine Art Conservator Julian Baumgartner on His Most Memorable Restoration Feats

The Chicago art conservator reflects on his time with the family business.

The Chicago art conservator reflects on his time with the family business.

Artnet Price Database Team

There is only one tool trusted by art world insiders to buy, sell, and research art: the Artnet Price Database. Its users across industries—from auction houses to museums, galleries, and government institutions—represent the art world’s most important players. We’re taking 15 minutes to chat with some of the Artnet Price Database’s power users to get their take on the current state of the market and how they’re keeping up with the latest trends.

Julian Baumgartner wears many hats at his eponymous Chicago restoration studio. As the sole proprietor of the city’s oldest conservation studio, started by his late father R. Agass Baumgartner in the 1970s, Julian serves the role of owner, conservator, secretary, janitor, accountant, shipping manager, and much more.

Ironically, Julian never dreamt of taking over his father’s business. Instead, he wanted to be a working artist, and studied painting and printmaking at the State University of New York’s Purchase College. But, when he began an apprenticeship with his father after graduation, he fell in love with the process of restoring the artist’s vision to the canvas.

Read on to learn about the greatest challenges of art restoration, and the John Singer Sargent painting that he would “give up a finger to own.”

A restoration work in progress. Courtesy of Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration.

Can you tell us about the history of Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration? What is the company’s mission?

The business was started in the late 1970s by my father after he immigrated to Chicago from Switzerland where he was a practicing conservator for many years. I began apprenticing under my father from the time I was born, as I spent many weekends, sick days, and holidays in the studio immersing myself in materials and artwork writ large. When I began studying studio arts in college, I worked summers at the studio sweeping and organizing—general grunt work that my father was all too happy to pass off. Slowly, I became more interested in the actual craft of conservation. When I graduated from university I asked my father if I could work with him, to which he responded “No.” My retort was that he should plan on me living in his house for many more years. He then told me that work started on Monday at 8 a.m. sharp. That was the beginning of a five- or six-year apprenticeship that saw me learn the art of conservation.

Did you always imagine that you would follow in the footsteps of your father to pursue art restoration?

Certainly not. I had dreams of being a working artist, and couldn’t fathom carrying on the business. Yet the more time I spent at the studio, the more seduced I became. Conservation would allow me to live in the world of art and work with my hands and materials while not having to shoulder the burden that so many artists face.

What is the greatest challenge of the art restoration process?

The coy answer here is that the paintings are easy, it’s the clients that are difficult. The reality is that balance is the most difficult part of the job, much like anywhere else. Making sure that the work is balanced so that deadlines can be met, sanity can be saved, and everything runs smoothly requires constant maintaining. The work itself is a pure joy so long as it’s not rushed or compromised by external actors.

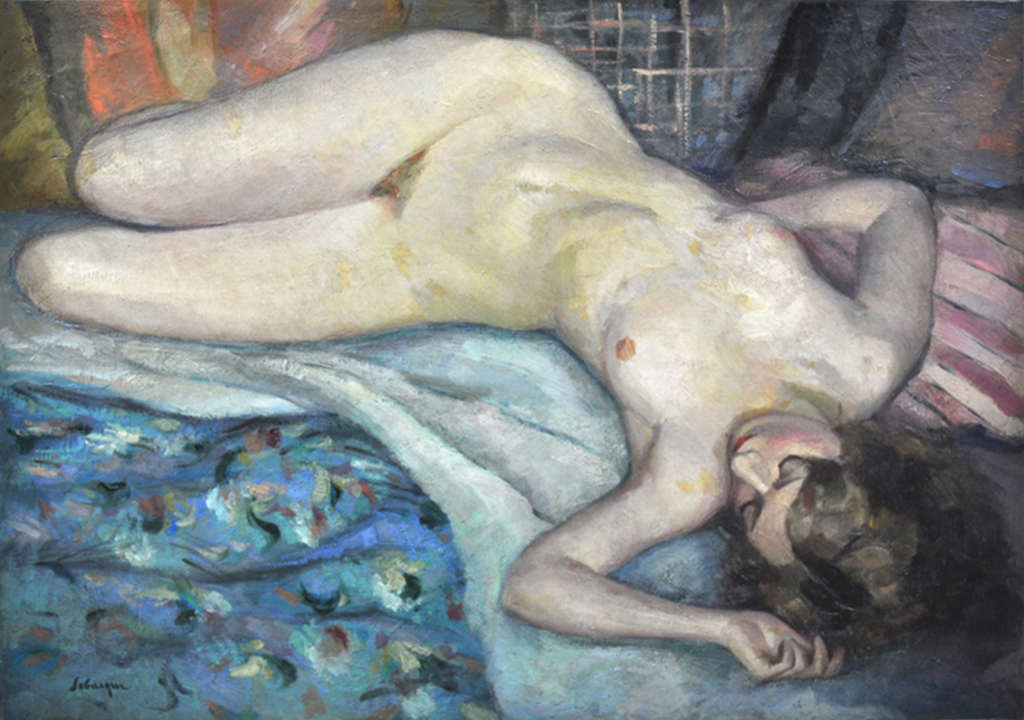

Untitled (Reclining Nude) by Henri Lebasque was successfully attributed with help of Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration. Courtesy of Julian Baumgartner.

What steps go into restoring a painting from first evaluation to the finished product?

I often say that I work first for the artist in the preservation of their abstract idea, second for the object in making sure that it can have an existence in the future, third for the client in understanding and meeting their wants and needs, and finally for myself in ensuring that the work I execute is archival, fully reversible and in accord with the AIC code of ethics. It’s the responsibility of the conservator to find a way to balance all of those sometimes conflicting elements, and if done well, success is a matter of execution. Beyond that, every artwork is unique, even two pieces from the same artist, so it is paramount that preconceptions be checked and fresh eyes are brought to every project.

Beyond restoration, you also conduct research to attribute paintings to their artists. What is the most memorable research project you have conducted?

Purchased at auction, the painting Young Fisherman, Hudson River Palisades sat for several years with the owner until inquiries from known galleries and dealers piqued their interest. With no signature and no provenance, the artist remained a mystery. Through extensive research, the owner had narrowed down possible artists but had come to an impasse as there existed no history of the work. The owner brought the painting to the studio and after an examination, including ultraviolet and infrared photography, the remnants of a previous sketch were discovered. This sketch, invisible to the naked eye, turned out to match exactly a page from the sketchbook of George Caleb Bingham, a noted Hudson River School painter. Working with the owner and the author of Bingham’s catalogue raisonné, the painting received legitimate attribution, a working title and inclusion in the next printing of the raisonné.

Young Fisherman, Hudson River Palisades by George Caleb Bingham. This work was successfully attributed by Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration. Courtesy of Julian Baumgartner.

How do you envision the future of Baumgartner Fine Art Restoration? What about the restoration industry as a whole?

Restoration and conservation are ever evolving fields, and any operator within that space must understand this and embrace it. I, along with my colleagues, are always looking to new approaches, materials, and technology to assist our pursuits, and as such we must design our business around the core principle of being supremely adaptable. What was common practice 20 years ago is no longer the norm and techniques that were used 100 years ago but fell out of favor 50 years back are now being revisited. The methods of art making have changed radically in the last 40 or 50 years and untested materials, novel construction methods, and unique practices of artists will present unimaginable challenges for conservators in the future. It’s an incredibly exciting time to be a conservator.

Do you collect any art? If so, what is your favorite item in your collection?

I have a small collection of varied works of art. Many from friends and some that have simply caught my eye along the way. The great part of being a conservator is that I spend my days inside an ever revolving collection of art that fulfills all of my artistic appetite.

If you could own any one artwork on earth, regardless of price or size, what would it be?

John Singer Sargent’s Lady Agnew of Lochnaw. I’d give up a finger to own that painting—just not on my retouching hand.

As an art restorer, what is one thing you like to search for in the Artnet Price Database?

I generally use the database as a non-economic research tool. Price isn’t all that relative for me, but the extensive database of images and provenance is extremely helpful when I’m trying to find reference images of an artist’s body of work for use in retouching, or in trying to help a client determine where their artwork falls in an artist’s catalogue.