Art World

15 Minutes With a Price Database Power User: Tate’s International Art Curator Osei Bonsu on His Approach to Research

We spoke with the curator about his working process, his favorite exhibitions, and what he learned from Okwui Enwezor.

We spoke with the curator about his working process, his favorite exhibitions, and what he learned from Okwui Enwezor.

Artnet Price Database Team

There is only one tool trusted by art-world insiders to buy, sell, and research art: the Artnet Price Database. Its users across industries—from auction houses to museums, galleries and government institutions—represent the art world’s most important players. We’re taking 15 minutes to chat with some of the Artnet Price Database’s power users to get their take on the current state of the market and how they’re keeping up with the latest trends.

“Growing up as a child of mixed Ghanaian and British heritage, I was always aware of the richness and complexity of black culture, our political struggles, as well as our literary and artistic traditions,” says Osei Bonsu, curator of International Art at Tate Modern, who oversees the presentation and collection of art from Africa.

“But I couldn’t seem to find spaces where these histories were being acknowledged. I decided to pursue a career in art because I wanted to change that.”

We spoke with Bonsu, a mentee of the late Okwui Enwezor, about which artists he thinks have not been given enough scholarly attention, and how he approaches contemporary art from an institutional perspective.

What did you study in school? Did you always know you wanted to be a curator?

I studied curating at Central Saint Martins before going on to complete a Masters in History of Art at University College London. I started out with a broad focus on post-War and contemporary European and American art, specifically the Arte Povera movement and its relationship to global politics. Gradually, I began specializing in Modern and contemporary art from Africa and the diaspora. I moved to London having grown up in a small village in Wales, so the concept of curating wasn’t at the forefront of my mind as a child. However, I was a voracious reader and always imagined I’d end up working in the arts. My first art job was as a tour guide at the National Museum of Wales in Cardiff, where I became fascinated with European Impressionism.

What does your curatorial process look like? How do you find inspiration, and form that starting idea into a cohesive narrative?

Like any other form of artistic practice, it requires a lot of dedication, self-motivation and a certain kind of obsessional neurosis. For me, the process typically begins with writing, which is a way of establishing a foreground for a project. I like bringing disparate narratives and histories together, many of which will inevitably precede the artwork. I often find inspiration by reading the writings of thinkers whose ideas inform how I understand broader issues of history, identity and politics.

In 2017, I curated an exhibition at Jeu de Paume in Paris titled “The Economy of Living Things,” which included new commissions by Oscar Murillo, Ali Cherri, Steffani Jemison and Jumana Manna. The exhibition looked at the notion of migration through the movements of non-human forms such as plants, consumer goods, and museum artifacts.

The exhibition was inspired by the writings of the political scientist Françoise Vergès, with whom I collaborated on the project, as well as the canonical writings of authors like Paul Gilroy, Edouard Glissant and Franz Fanon, whose ideas form the foundation of my approach to debates around contemporary art and culture.

Still from Ali Cherri, Somniculus. Shown as part of The Economy of Living Things at the Jeu de Paume.

Do you have a favorite museum exhibition, whether put on by the Tate or any other institution, and why?

In 2015, I was fortunate to work with the late curator Okwui Enwezor, who was a mentor and friend, assisting on his seminal exhibition, “All the World’s Futures,” at the 56th Venice Biennale. Speaking with my friend Samson Kambalu recently, I realized how instrumental the exhibition was in terms of understanding the relationship between contemporary art and the times we live in.

When the first biennale of Venice was inaugurated in 1895, there were no pavilions, and therefore the concept of national representation through art did not exist. The exhibition used this idea as a point of departure to explore how social and political changes relating to questions of nationhood and its political power structures transformed the global map. It was important because it addressed the inescapable disquiet of our times, from mass migration to mass mobility, environmental catastrophe to genocidal conflicts. The mission of the exhibition is not to arrive at a single point of understanding, but to offer space for diverse forms and practices to coexist at the same time—as a constellation of ideas.

How do you approach curating from the perspective of contemporary art, where the story is still being written?

I try to approach historical and contemporary art in the same way, which is to say that the story has always yet to be written or indeed, rewritten. The challenge of curating contemporary art is to provide it with a meaningful historical context, the same is true in reverse.

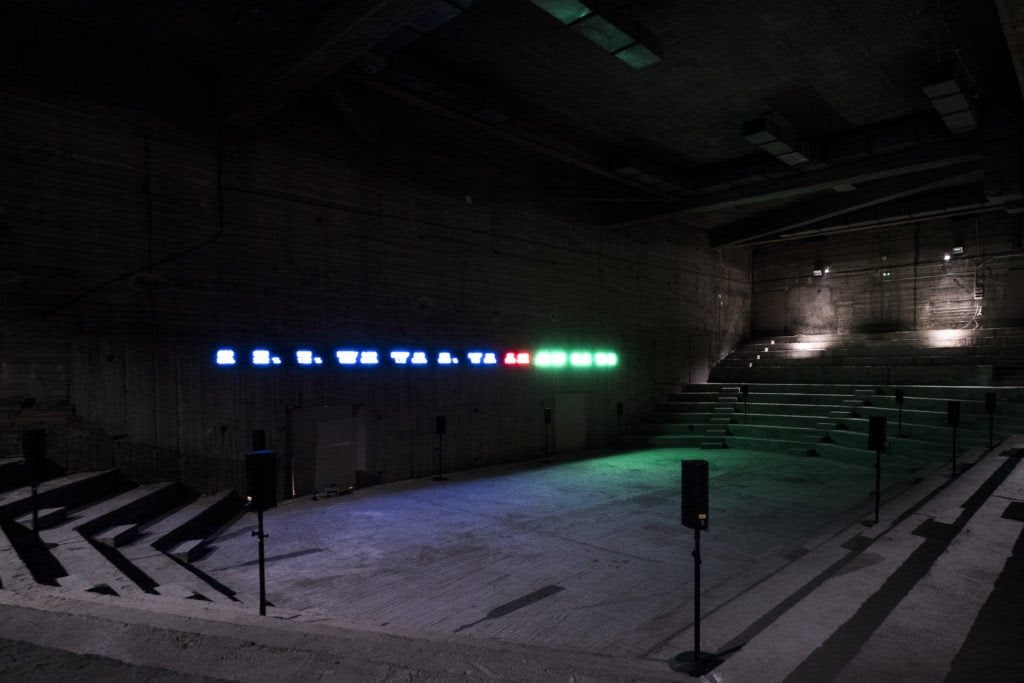

Emeka Ogboh, The Way Earthly Things Are Going (2017). Photo: Mathias Voelzke.

What are some trends you see emerging in the global art market around African contemporary art?

I try not to focus on trends as such, but rather on works that pose questions that transcend our current moment. I recently led a trip to Lagos with Tate’s Africa Acquisitions Committee and it was incredible to see how the art scene is developing at speed in Lagos, with a flagship biennale, emerging art fairs and a small yet buoyant gallery scene. I believe the future of African art is in the hands of local art ecosystems across the continent.

Today, I am interested in artists who use their medium to tell stories about the world we live in. Take, for example, the Nigerian artist Emeka Ogboh whose immersive installation The Way Earthly Things Are Going was presented in the Blavatnik Building of Tate in 2017. The work features live-streamed stock exchange data which scrolls along the wall in LED displays. At the same time, an enchanting ancient Greek lament, “when I forget, I’m glad,” creates a polyphonic chorus of voices. As the all-too-familiar tales of exile and forced migration flood the space, we realize that this is a work about the Greek economic crisis and the relationship between migration and global capital. Art should always seek to raise issues and broaden perspectives.

Which artists have not yet gotten institutional attention that you think deserve it?

There are so many artists whose work has been lost in the sands of time. One of the artists I’ve been thinking about recently is the British artist and photographer Ingrid Pollard. Her work uses portraiture photography and landscape imagery to explore social constructs of identity and racial difference.

I included her work in an exhibition, “Counter Acts,” that I organized looking at the history of the Turner Prize at University of the Arts London in 2019. “Counter Acts” explored the relationship between artists and art schools during a period of political and cultural transformation in Britain. Ingrid is one of the few artists from the Black British Arts movement in the 1980s who has not been sufficiently discussed or highlighted by institutions.

What was the last thing you searched for in the Price Database?

Samuel Fosso’s African Spirits.