Galleries

2015 Turner Prize Show is Earnest and Experimental but Ultimately Anticlimactic

Why do we still care about the Turner Prize so much?

Photo: Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

Why do we still care about the Turner Prize so much?

Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

On Wednesday, the 2015 Turner Prize exhibition held its preview at Tramway, the Glasgow art institution that’s hosting the prize this year. Sarah Munro, the outgoing director of the venue, and Paul Pieroni, co-curator of the exhibition, welcomed the throngs of arts journalists that included the top national newspapers and leading art magazines.

Expectations were high. The Turner Prize, the UK’s most famous art award, which celebrates its 32nd anniversary this year, still commands much media attention and speculation.

The nominees of the 2015 award feature three women—Bonnie Camplin, Janice Kerbel, and Nicole Wermers—and the young, 18-strong architecture collective, Assemble. Its high ratio of women artists and the inclusion of a discipline not usually featured in galleries and museum have been rightfully celebrated both in the art world and in the media at large. So has been the choice of Glasgow as host, highlighting the status of the Scottish city as the second most important arts hub in the UK, and challenging its London-centric image (even if the four nominees are all London-based).

Installation view of Nicole Wermers’s Untitled Chairs (2014-15) at the 2015 Turner Prize exhibition in Tramway, Glasgow.

Photo: Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The first project the viewer encounters is Wermers’s, who was nominated for her exhibition “Infrastruktur” at the London-based gallery Herald St. Ten chairs, based on Marcel Breuer’s design classic Cesca, sit in the gallery room in different formations: In twos, threes, alone. The artist has sewn fluffy and glamorous fur coats into the backrests. The juxtaposition of the common chair and luxurious coats plays on the gesture of claiming a seating or a spot in a public area, in a bar, cinema, on the train. The gesture is certainly familiar, we’ve all done that.

On the walls, there are three ceramic sculptures that imitate the form of home-made tear-off notices pinned to communal notice boards or stuck on street lamps by individuals searching for lost cats, offering baby-sitting services, or selling property. The rugged outlines of the sculptures are familiar, but their ceramic surfaces, white and washed out, are ghostly and somehow beguiling.

Performance of Janice Kerbel’s DOUG (2014) at the 2015 Turner Prize exhibition in Tramway, Glasgow.

Photo: Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

Nearby, a large gallery room sits empty but for a few screen-prints of a score pinned to the walls, and a cluster of black music stands. A few minutes later, a choir of six singers and a conductor enter the space and proceed to perform a 24-minute opera about a series of disasters that befall a fictional character (including falling down the stairs, being struck by lighting, and choking). The concept is tragicomic, no doubt, but the avant-garde style of the composition—which features a series of cacophonies combined with melodic bars—turns it into a self-conscious, self-serious affair.

Installation view of Assemble’s A Showroom for Granby Workshop (2015) at the 2015 Turner Prize exhibition in Tramway, Glasgow.

Photo: Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

In the back of the large gallery space, Assemble is presenting a showroom with the range of products made in the workshop they created in Liverpool’s Granby Four Streets, engaging the local community in the production of the features the collective designed to refurbish the empty houses in the area, to create affordable social housing. The projects is a sprawling combination of architecture, urban regeneration, community engagement, and beautiful craftsmanship (including marbled mantelpieces, glazed ceramic tiles, and terracotta lampshades).

The display at Tramway, however, turns a highly fluid endeavor, based on collaboration, into something static; a socially engaged project thus becomes solidified as a commercial display of sorts. I have no question whatsoever that the practice of Assemble has a rightful space within the museum realm. I wonder, though, if it could have been better conveyed through a series of participatory workshops and events, in which members of the public could have experienced their activities in a less passive manner.

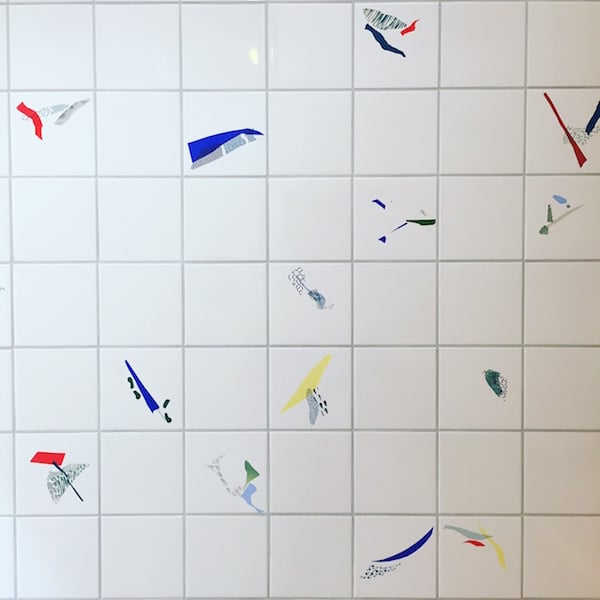

Installation view of Bonnie Camplin’s Patterns (2015) at the 2015 Turner Prize exhibition in Tramway, Glasgow.

Photo: Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The last project on the itinerary is Bonnie Camplin’s Patterns, based on The Military Industrial Complex, which the artist presented last year at the South London Gallery. The piece takes the form of a study room, in which a large number of publications on a wide range of subjects—including conspiracy theories, philosophy, science fiction and psychology—complement five video interviews with subjects explaining their extraordinary experiences, such as being abducted by aliens.

The work, which explores the concept of “consensus reality”—what we take for being real and credible and what we disavow—is certainly compelling. But, as a piece of so-called “research-based art,” it fails to convey the rich and unique visual sensibility that works by Camplin in other media such as film, performance, and drawings posses.

As a whole, the exhibition felt somewhat anticlimactic. Not because of the four shortlisted projects, which were all convincing and interesting in their own different ways. And neither was it because of the exhibition space, generous and glistening under a very flattering natural light, nor the exhibition design, which was flawless.

Assemble’s A Showroom for Granby Workshop (2015) at the 2015 Turner Prize exhibition in Tramway, Glasgow.

Photo: Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

The question is, in an art world which has boomed enormously since the Turner Prize was first launched in 1984, and which now offers top-notch exhibitions by the hundreds, both in London and regionally, as well as a healthy selection of UK-based art prizes (the Max Mara Art Prize and the Artes Mundi Award to mention a couple), just what is it that makes the Turner Prize still so relevant, so appealing?

Perhaps the answer lies in what Munro told me, stressing the broad appeal of the prize for the general public.

“I think [the Turner Prize] has a brand identity, it has this huge visibility and history around it,” she said. “I think it’s also a moment when the general public feels more welcomed into the art world. I’d love to see a rise in our first-time visitors, who might feel compelled to come to Tramway because it is the Turner Prize, and it is such an event, but maybe they have a great experience and they go on to become life long advocates of contemporary art.”

But no Turner Prize review would be complete without taking sides, which has become a sort of national sport from the moment the nominees are announced in the spring up until the winner is announced in December.

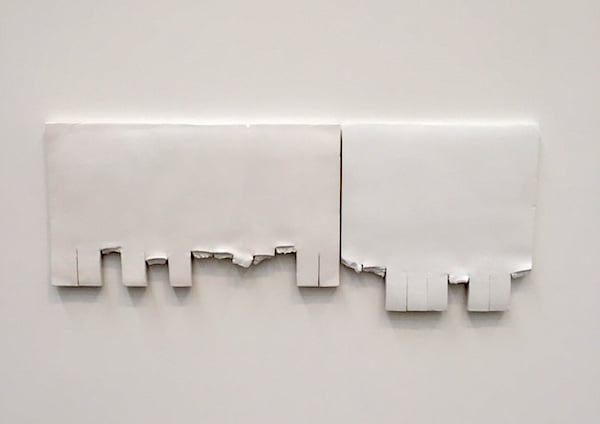

Nicole Wermers’ Sequence #G-11 (2015) at the 2015 Turner Prize exhibition in Tramway, Glasgow.

Photo: Lorena Muñoz-Alonso

Although I would have never thought myself particularly conservative in my taste in art, I found myself rooting for Wermers, who—due to her consistent engagement in the medium of sculpture—could be considered the most “traditional” artist of the lot.

Wermers’s Turner Prize project, and her oeuvre in general, has an evocative, intangible quality that only the best works of art have. Her project explores social mores and spatial concerns, but it does so through a distinctively sensual and (why not?) aestheticizing approach. The result is a sculptural installation that might seem simple in its subtlety, but which grows into something rich and mysterious, and a little disturbing.

Wermers’s sculptures invite the viewer to complete them, to build a narrative around them. And, sometimes, a bit of suspended reverie is the more rewarding—and also the most complicated—thing that one can demand of a work of art.

The 2015 Turner Prize exhibition is on view at Tramway, Glasgow, from October 1, 2015-January 17, 2016. The winner will be announced on December 7, 2015.