Art & Exhibitions

Here Are 3 Buzzy Shows to See in New York This Summer

From an Alex Katz outing to an installation of citrus trees that was decades ahead of its time, here is what the art world is talking about in New York this season.

Summertime in the New York art world often means large and playful 20-person group shows, which we love to see. However, some of the most talked-about shows in town are duo and solo outings; we have selected three exhibitions currently on view at New York’s premier arts institutions that are powerful displays spanning decades (and even centuries), each generating a lot of buzz and discussion.

Alex Katz, Summer 21 (2023). © Alex Katz / Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY. Courtesy of the artist and Gladstone Gallery.

The art world has caught up with Alex Katz over the past couple of years. Unfairly or not, the New Yorker’s paintings had long been considered lightweight compared to peers such as Jackson Pollock and Jasper Johns.

Not any more. Last year, the Guggenheim in New York staged “Gathering”, a retrospective offering up the people and places of Katz’s life. Venice’s Fondazione Giorgio Cini is presenting a series of new paintings to coincide with the Biennale. Now, MoMA has given over its second-floor atrium to “Seasons,” four monumental paintings that balance soft color and the openness of memory. As with Monet’s Water Lilies nearby, Katz’s paintings are immersive and environmental; autumn is a pang of yellow and summer is an overwhelming rush of greens.

The paintings largely emerged from photographs snapped on his iPhone during morning walks downtown and have been painted in big single strokes. “When you get more skilled, you can use a bigger brush for smaller things,” says the artist who has been hard at work for eight decades.

Hiroshige’s 100 Famous Views of Edo (feat. Takashi Murakami) at Brooklyn Museum

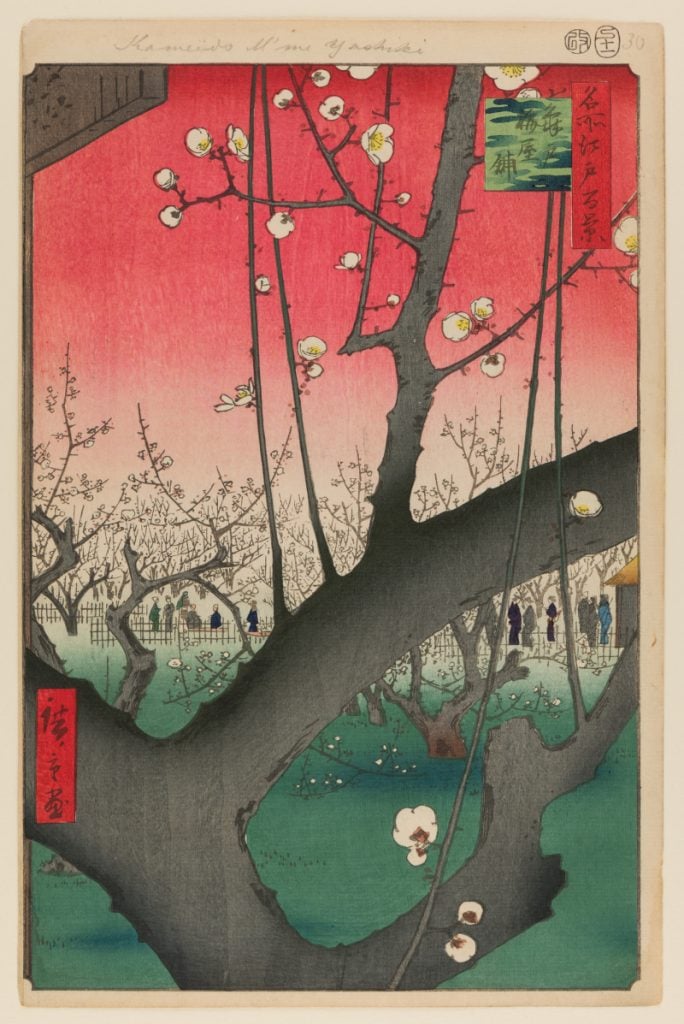

Utagawa Hiroshige, Plum Estate, Kameido (Kameido Umeyashiki), no. 30 from “100 Famous Views of Edo, 11th month of 1857.” Photo: Brooklyn Museum.

Sometime in the early 20th-century, the Brooklyn Museum received a remarkable donation: a bespoke edition of Utagawa Hiroshige’s “100 Famous Views of Edo.” Perhaps the museum forgot—these masterworks sat in storage for 40 years before being unveiled to the public. This collection of 118 works—the popularity of the series prompted further recent additions—includes vibrantly colored woodblock scenes and has gone on view again, after another large hiatus of 24 years.

The series immerses us in the 19th-century Edo of Hiroshige’s imagination. Kites at sunset race out of sight, shoppers scurry beneath the eye of Mount Fuji, the smoke of tile kilns wafts across the Sumida river, a solitary boatman pushes on through the driving rain.

Hiroshige’s mastery of composition and color stand as a hallmark at the end of the shogunate and would influence a generation of European artists including Claude Monet, Vincent Van Gogh, and James Whistler. At the Brooklyn Museum, they’ve influenced Takashi Murakami with the pop artist reproducing the entire series in acrylic and gold leaf—albeit it on a much larger scale.

To both Murakami and the viewer, Hiroshige’s “Edo” is a vanished, impossible place, but through these works we might be reminded of the preciousness of our own cities and the places therein that we cherish.

“Survival Piece #5: Portable Orchard” at the Whitney

The Harrisons, Survival Piece #5: Portable Orchard (1972–73), installation view, Art Gallery at California State University, Fullerton.© Helen and Newton Harrison Family Trust. Courtesy Various Small Fires, Los Angeles/Dallas/Seoul.

When Helen Mayer Harrison and Newton Harrison (known as the artist duo the Harrisons or the Harrison Studio), the late environment artist couple, first staged “Portable Orchard” at California State University in 1972, the question of food system sustainability may have seemed niche. Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring had caused concern over modern farming practices during the preceding decade, but these questions were far from commonplace in public discourse.

Part of a series in which the Harrisons posed practical solutions to navigate future ecological situations, “Portable Orchard” is made up of 18 citrus trees housed in planters with individual lighting systems. Executed by following detailed instructions from the artists (including citrus recipes), the sensorial work calls into question existing food production systems and human’s need for real sustainability.

The 1970s work was far ahead of its time and given the revelations of recent science, this latest installation at the Whitney arrives in a drastically different context. “Portable Orchard” though prophetic, feels less dystopic.