Artists

3 Works by Pioneering Artist Rebecca Horn That Changed Contemporary Art

Through performance, sculpture, and installation, Horn explored what it is to inhabit a body in our technological age.

Through performance, sculpture, and installation, Horn explored what it is to inhabit a body in our technological age.

Jo Lawson-Tancred

The German artist Rebecca Horn has died aged 80 in the town of Bad König on September 6, her foundation and gallery have confirmed. She is remembered for her visionary choreographies of body, space, and machine through the mediums of of performance, sculpture, and installation. Her work was a bellwether that anticipated artistic movements still yet to come.

“Rebecca was a heroic, pioneering artist whose fierce independence, energy, and spirit touched everybody who came into her orbit,” said Sean Kelly, Horn’s gallerist for nearly four decades. “I am honored to have had the privilege to work with her and to have been able to call her my friend. She will be greatly missed.”

Horn was born in the town of Michelstadt in 1944 to Jewish parents who were forced to hide with their baby in the Black Forest until the war was safely over. She grew to love drawing from a young age and it became an important source of solace when she was hospitalized for tuberculosis as a teenager.

Rebecca Horn. Photo: Gunter Lepkowski Germany, courtesy of Sean Kelly Gallery.

Struck by illness again at the age of 20, Horn was forced to drop out of the Hamburg Academy of Fine Arts after working with fiberglass without a mask and suffering severe lung inflammation. She spent a year recovering in a sanatorium before continuing to make sculptural works but expanding into performance art, installation, and film. A fascination with both the possibilities and limitations of inhabiting a body would never leave her.

Over a six-decade career as an artist and teacher, Horn lived in London, Paris, New York, and Berlin, before setting up the Moontower Foundation in Bad König, Germany in 2010. She participated twice in Documenta, first in 1972 and a decade later in 1982, and has been given solo exhibitions at the Nationalgalerie in Berlin, the Serpentine and Tate in London, the Guggenheim in New York, and MOCA in Los Angeles. Her work is currently the subject of a retrospective at the Haus der Kunst in Munich until October 13th.

Artnet News takes a look back at the considerable breadth and prescience of Horn’s work.

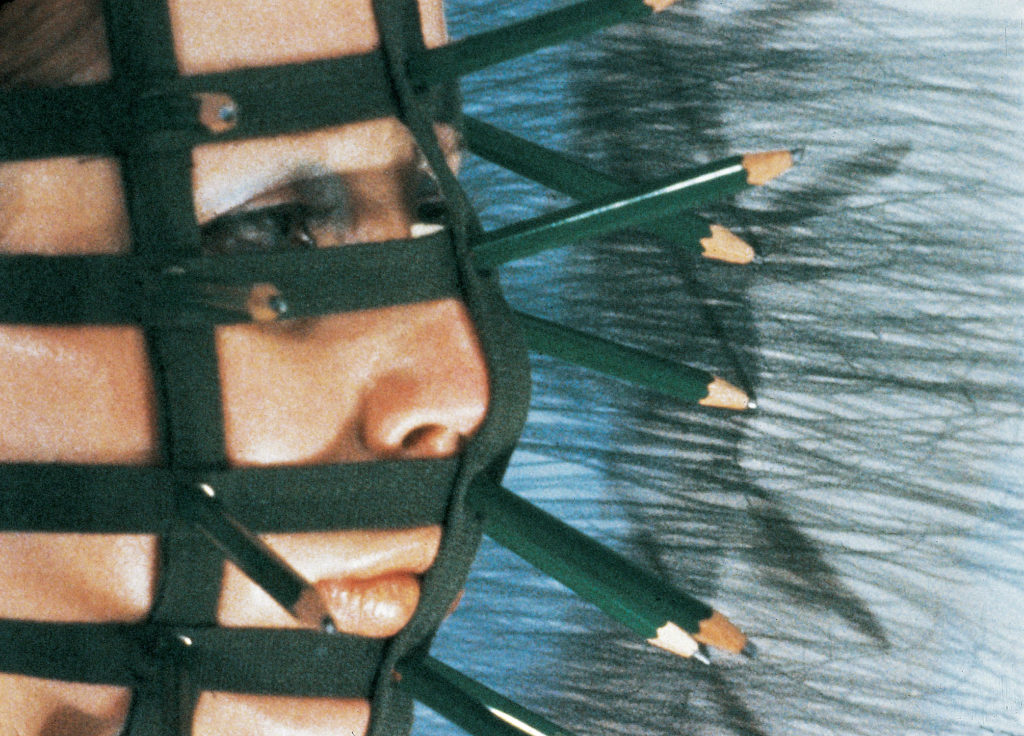

Pencil Mask (1972)

In the early 1970s, Horn embraced the classic postmodern medium of performance art. Exploring our assumed bodily boundaries, she invented wearable sculptures that allowed her to expand into her environment in new and unexpected ways.

One example is the Pencil Mask, a strange cage-like contraption that can be strapped to the wearer’s head so that sharp pencils protrude from her face. Now, as well as a human, she becomes an instrument for crude drawing.

“All pencils are about two inches long and produce the profile of my face in three dimensions,” Horn explained. “I move my body rhythmically from left to right in front of a white wall. The pencils make marks on the wall the image of which corresponds to the rhythm of my movements.”

The Peacock Machine (1982)

Rebecca Horn, The Peacock Machine (1982) installed at Haus der Kunst in Munich, 2024. Photo: Markus Tretter, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024.

In the early 1980s, Horn began making motorized sculptures of which one of the first was Peacock Machine, conceived for Documenta 7 in 1982. Out of the strange automaton protrudes long aluminum rods that fanned out like the tail feathers of a peacock.

The artist herself described the work in a poem, writing of how, “sparked by the cries of the courting male peacocks, a machine in the center of the eight-sided temple begins to stir and spreads its long metal feelers fan-like into the room, in deep concentration, startled as it brushes against the wall, soothed by the sound of the golden waterfall, the opened semicircular fan dips down to the floor protectively closing off the room.”

Like many machines from everyday life, the sculpture repeatedly carries out a motion sequence that gives it the impression of being alive. In this way, the uncanny object seems to be part-animal and part-machine, an ambiguity inherent to some technologies that has only become more relevant in the decades since.

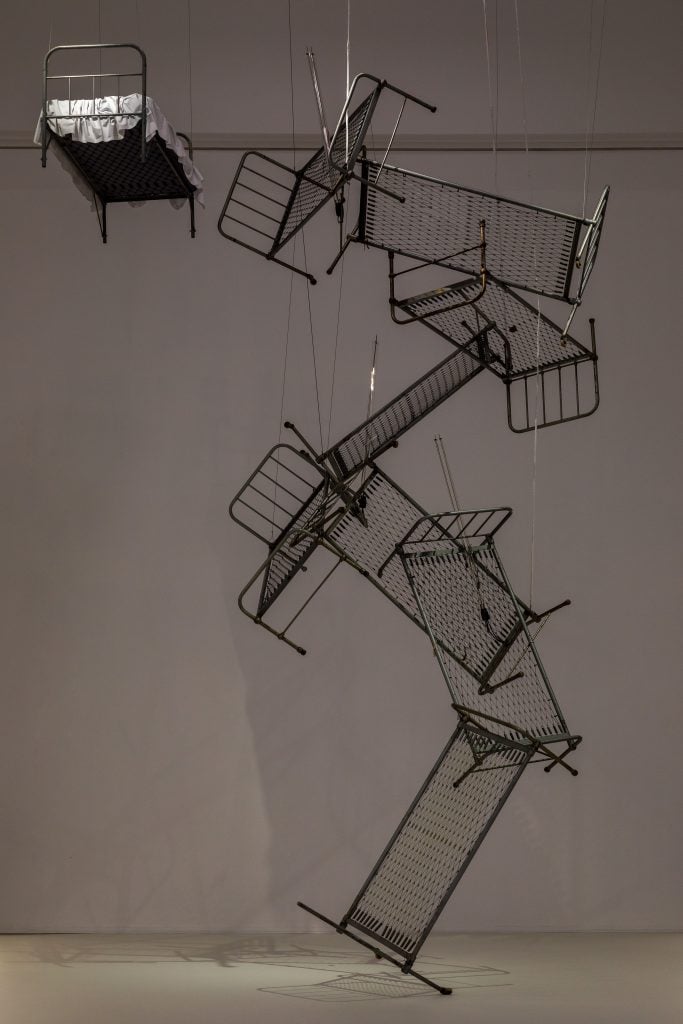

Inferno (1993)

Rebecca Horn, Inferno (1993) installed at Haus der Kunst in Munich, 2024. Photo: Markus Tretter, © VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn 2024.

By the 1990s, Horn had began producing large-scale installations, of which Inferno is one of the first. Classic metal-framed hospital beds from a psychiatric ward, bare but with their springs intact, have been wedged together in a interlocking, stacked mass that is suspended from the ceiling. The tall structure is embedded with glass tubes that periodically flash in the manner of lightning.

Hovering near the top, is a singular bed made up with a mattress and sheets, as though still in use. The work’s title is a reference to Dante’s first canto of the Divine Comedy.

The seeming precarious installation is eery and evocative, casting beds not as a place of restoration but potential sites of great suffering. The viewer is left to imagine the relationship of the human body, perhaps their own, to the work.