In light of the onslaught of pernicious press about the current state of the art market, I asked Don and Mera Rubell at the Armory Show last week if their voracious collecting appetites have decelerated, or worse, ceased. Don replied, “We haven’t bought anything…” before trailing off with a pregnant, worrisome pause, then adding, “…for 24 hours.” After which, without missing a beat, they resumed their negotiations with Templon Gallery. That was music to the ears of this 62-year-old mid-career emerging artist, whose second solo show at Nagel Draxler Gallery in Cologne just opened a little more than a week ago. (Read on.)

This summer (and fall: make it stop, please) has offered up, by far, the most hyperbolized headlines I have ever seen. There are way too many to list, as it would fill this whole article, which I’d do if I were getting paid by the word. (I’m not.) The R-word, recession, is on everyone’s lips—the possibility of one, at least. However, if a recent visit to the Armory is any indication, it’s business as usual, though market momentum has clearly slowed. Checking in for a flight over the summer, an airline attendant mentioned that she was a Sorbonne-trained art historian but can make more money working part-time at the airport while still being able to peruse art. (But when has anything ever been easy?)

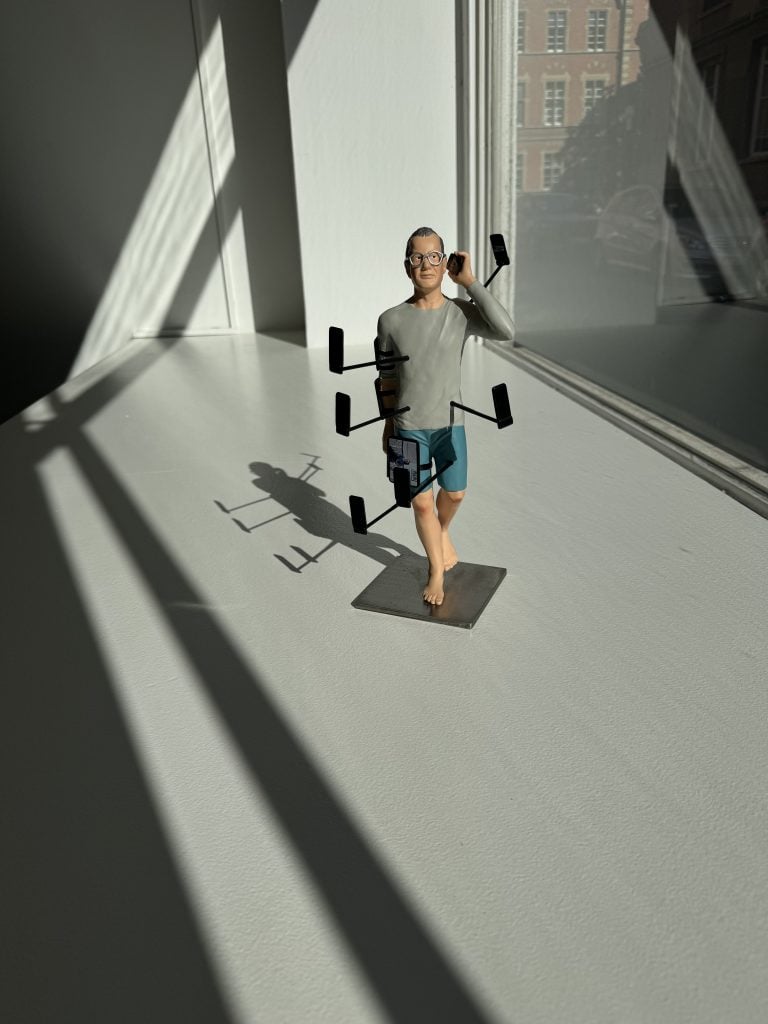

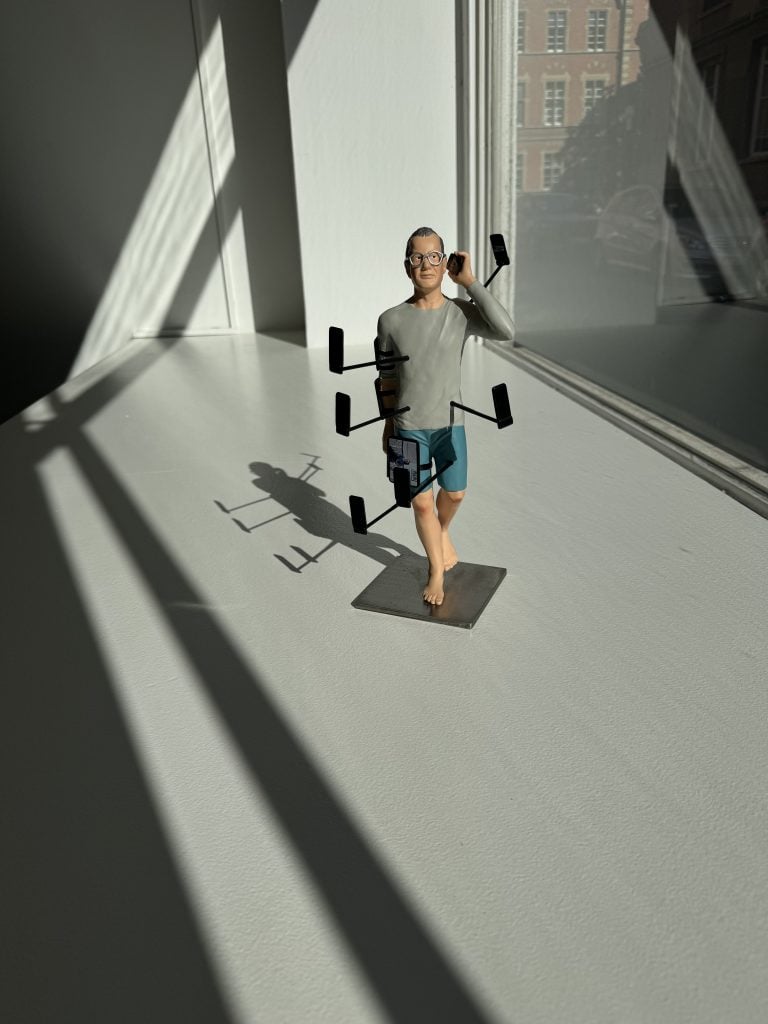

“Phone Face,” the title of my exhibition at Nagel Draxler focused on the digital age and the fact that we live largely through the intermediary of the screen. Mini selfie-man, edition of 10 in cast aluminum. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter and Nagel Draxler

The most egregious, blaring of the lot (in the New York Times in August, by Zachary Small and Julia Halperin, my esteemed former colleague) shrieked: “Young Artists Rode a $712 Million Boom. Then Came the Bust. Artists saw six-figure sales and heard promises of stardom. But with the calamitous downturn in the art market, many collectors bolted—and prices plummeted.” The three artists described in the piece barely warranted mentioning as representatives of anything in particular, with prices that are a stretch at five figures, let alone six. Apologies, I don’t mean to be flippant, I’m just a little riled.

Plenty of contemporary artists are doing just fine and some, much better than that, but that’s irrelevant. Artists make art whether there are buyers—and high prices—or not, and I’m the perfect example (insert hysterically laughing sideways emoji). Even worse than the click-baiting article above are musings about collectors abandoning art to accumulate sneakers, handbags, or dinosaur bones—or instead buying experiences, not wanting to be bothered by the burden of ownership.

Adrian Schachter’s riff on Bruce Nauman’s fountain photo from his summer exhibit at Saint Moritz’s Super Mountain Market pop-up. Photo courtesy Kenny Schachter

Back in June, journalist Scott Reyburn wrote in the Art Newspaper: “Does the De la Cruz collection sale mark the end of an era? Reduced value, mixed results dent idea of contemporary art as investable asset.” Reyburn, whom I count as a friend, has never been much of a market maven, which is a twisted position for a widely published writer on the subject. He states in the above piece: “Nowadays the young collect moments, not physical objects…” A counterexample comes from Adrian Schachter, my son, who was recently the subject of two sold-out exhibitions, the first at Amanita Gallery New York in March and then at a pop-up in St. Moritz in August (after a residency in the Engadin).

The demand for Adrian’s paintings was so strong—with collectors from his generation (20-somethings) up to mine—that I couldn’t get one myself. Besides providing fodder for the next family therapy session, this offers hope for the future of the profession, if not for me. Art is like a cockroach (the New York City variety): it thrives in good times and bad, among rich and poor. Art courses through our circulatory system and always has, since it was applied to cave walls, and it always will, through all but a nuclear conflagration. Macroeconomic cyclical vicissitudes will never block (interrupt, yes) the human trait that differentiates us from every other species: making and experiencing art.

“S-a-t-u-r-d-a-y Night,” a 1973 song by the Bay City Rollers; and, just another wild and wacky—and violently dangerous—night in Cologne! The front door of the Excelsior Hotel after a hit and run by an errant wine bottle. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter

Though I am often accused of gossip-mongering, I recoil from being labelled a gossip writer and prefer investigative journalist (if you’ll indulge me). But hey, who doesn’t, at least tacitly, love some chitter-chattering chinwag? To the clamor about artists and galleries in distress, add this: Sotheby’s is down so much that it’s clawing fees from sellers that are customarily absorbed by auction houses. That means that, if you fail to meet a certain sales threshold ($5,000), you have to pay the house an out-of-pocket penalty tacked onto the standard fees. Fun.

Again, for every dark cloud overhead, there’s a silver, or rather pigment-and-canvas, lining. In this instance, I can break the news that Magritte’s Empire of Light coming up at Christie’s in November has been irrevocably guaranteed for $80 million, in line with the previous record set at Sotheby’s in 2022, which was for a more commercial iteration of the series (there are 17 canvases in total). (Christie’s did not reply to a request for comment.) Stick that in your art-market-is-over, this-is-not-a-pipe pipe and smoke it.

True enough, I can’t do a lot of things, and that (or anything else) won’t stop me from trying. Failing is all part of the game, and you can’t go forward without stumbling back. And that I do aplenty. Photo courtesy of Simon Vogel and Nagel

New York dealer Per Skarstedt has agreed to pay $13.5 million for the Richard Gluckman-designed 25th Street gallery space of (now-shuttered) Cheim and Read, while maintaining his premises on East 79th, he confirmed. To paraphrase a line from Raging Bull, that’s a prominent stage for a bull to rage. Meanwhile, Yusaku Maezawa is in the process of transforming his newfound Basquiat bucks, reaped from the previously reported (by me) $200 million sale, to Ken Griffin, into a major Rothko acquisition.

Griffin, himself one of the highest-profile trophy hunters for market masterworks, has what I would call an encyclopedia collection (or a Wikipedia collection, for those too young to be familiar with encyclopedias). Meaning, if you look up an artist online or otherwise and find the most ubiquitous example of their work, that’s what Griffin tends to buy. I wouldn’t exactly say he is helping the state of connoisseurship, and he’s been known to turn down a work after long deliberations based on nothing more than his color preferences.

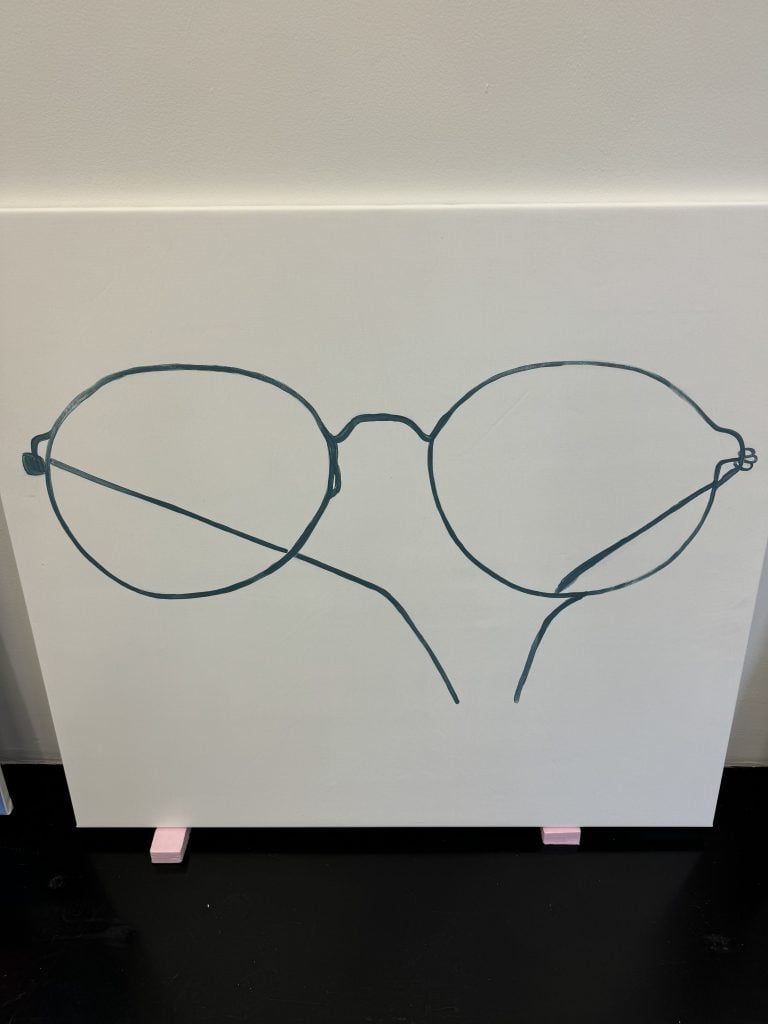

Readily owning up to my (lacking) painting skills, I work with the astounding robotic-painting tech company Matr Labs, translating my digital imagery onto canvas. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter

The legendary Daros Collection controlled by Swiss investor Stephan Schmidheiny sold its cache of Basquiat paper works a while ago for in excess of $100 million to Laurene Powell Jobs, via Iwan Wirth, who wrested her from the clutches of Pace in another round of the art world’s favorite zero-sum game: One dealer’s gain (using whatever coy innuendos and subterfuge at hand) almost always comes at another’s expense. (Wirth did not reply to a request for comment.) To add to their woes (or not), Pace’s short lived representation of Jeff Koons has come to an end, almost certainly due to the artist’s notoriously excessive fabrication costs, coupled with soft sales.

I hear the departure of Andrew Fabricant from his position as chief operating officer of Larry G Enterprises was goosed by whispers from dealer and Warhol expert Stellan Holm, a confidante of Gagosian, that Fabricant had been talking about the gallery dismissively. The art world can be, and often is, a venomous viper pit.

When I asked Holm for confirmation, he shot back, “Don’t you have anything better to do than gossip?” That word again. Which is rich coming from Stellan, one of Larry’s official circle of court jesters. Fabricant had no comment other than a passing mention of Shakespeare’s Hamlet and the character of Polonius, a busybody who meddles to the point of a tragic demise. By the way, Holm may have also had a hand, or auction paddle, in the beginning of the end of the Inigo Philbrick scandal, but I’ve said enough and don’t want to commit a Polonius myself.

Art and my family sustain me. Literally. Without either I wouldn’t be sitting here typing this. Photo courtesy of Anna Polke

Enough of the bullshit, how about some art?

The backdrop for my second solo exhibition at Nagel Draxler in Germany, which opened August 30, was the 16th iteration of the Düsseldorf Cologne Open Galleries weekend and local elections in Thuringia and Saxony, where the radical right-wing party AfD (Alternative for Germany) made substantial gains. Shortly before my arrival, there was a fatal stabbing (with three casualties) by an asylum-seeker squarely between Cologne and Düsseldorf. Mass killings are not just the province of the United States, though we certainly set the bar high.

Today, Cologne reminds me of New York in the 1970s. Forget anarchy in the U.K., it’s chaos in Cologne. As the radical right and left wangle for power, Germany is suffering infrastructure problems as bad as New York’s 50 years ago (or today), from chronically late trains—I spent inordinate hours getting from Cologne to Düsseldorf—to crap wifi. In fact, they don’t even release exact train-arrival times anymore; rather, mere estimates! Just the other day, the entire transit system went down from an IT fail. I felt right at home.

On a more positive note, before I touch upon my own outing at Nagel Draxler, there were some wonderful shows, including Isa Genzken at Daniel Buchholz, where a sculpture included a painted photo by Gerhard Richter (a Cologne resident) who was married to Genzken from 1982 to 1993. Call it revenge art. There was also a wild contraption by the L.A.-based Italian sculptor Piero Golia (repped by Gagosian) at JUBG, a space founded in 2021 with a specialization in art with a musical component. It’s co-owned by art advisor Alexander Warhus, artist Albert Oehlen, and musician Jens-Uwe Beyer, a tech-house performer professionally known as Popnoname.

The language of the kids, the net, and just about everyone in-between, as depicted on my cube sculptures as art, chair, table, or anything else you fancy if you buy it! “Phone Face” install image courtesy of Simon Vogel and Nagel Draxler

Oehlen is not just one of the foremost living painters (Lord, I covet a work); he also made a scripted 2001 film, The Painter, which I’m hankering to watch, if anyone knows how. He is in the final stages of erecting a standalone storage facility to house his art collection, apparently named the Wendy Gondeln Collection, a nod to the 1973 horror movie Don’t Look Now starring Donald Sutherland. For some odd reason. There you go—refreshing evidence of fervid collecting activity.

Before my solo at Nagel Draxler (and after) I was overwhelmed by feelings of fear, futility, and insecurity akin to the experience of being caught exposed in public with your pants around your ankles. Not a pretty picture, especially in my case. A sense of excitement and anticipation was offset by a simultaneous desire for it to be over—as fast as possible—and to retreat. Prior to the exhibition, when I sought feedback about a body of paintings I intended to feature, I was told by someone I deeply respect and admire, in no uncertain terms, that I should not only forever refrain from painting, but from drawing, as well.

Kippenberger was accused of alcoholic antics and worse in a major German newspaper, and as a result, sculpted himself into a corner. I followed suit for my own reason. Kenny Can’t Paint, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself. Photo courtesy of Kenny Schachter and Nagel Draxler

After I wiped the tears away (yes, I’m actually sensitive, if you can imagine), I was inspired by the behavior of one of my heroes, Martin Kippenberger, another Cologne stalwart during his prematurely cut-short life, when he was admonished by a high-profile German newspaper in 1989 for his alcoholic antics, demonic public rabble-rousing (and worse). (Don’t miss the arresting 2012 biography on Kippenberger by his journalist sister, Susanne, which is anything but a hagiography: Kippenberger: The Artist and His Families, translated by Damion Searls and published by J & L Books.)

Kippenberger responded not by lashing out, as he was wont to do, but by creating one of his most enduring works, Martin, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself, a self-portrait as a remorseful child taken to the woodshed by pissed-off parents. Kenny Can’t Paint, Into the Corner, You Should Be Ashamed of Yourself was my riposte, the cornerstone (excuse the pun) of the show, along with 22 sculptural cubes with 3D, four-letter words spelling out phenomena to do with technology, social media, and youth culture. Each piece on view, 40 in all, had an NFT counterpart presented in collaboration with the pioneering platform MakersPlace. I know, great timing, after a recently reported 96 percent decline in that market, as well.

Video still from my work How the elections will change my life (1992), duration 44:12. (Filmed with an overhead camera affixed atop sewage pipes, since lost). Photo courtesy Kenny Schachter

In conclusion, you’ll be reassured to know, Wikipedia characterizes Endurance Art, quoting artist Tatiana A. Koroleva, as “involving some form of hardship, such as pain, solitude or exhaustion.” In a 1992 group show I participated in, “Ballots or Bullets: You Choose” (at Sally Hawkins Gallery in New York, curated by G. Roger Denson in late 1992), I performed oral sex on my wife for 44 minutes and 12 seconds, a comment on the fact that, no matter the outcome of the 1992 presidential elections, life would remain the same. That may no longer be the case if the orange (T)rump wins, but whether art is excessively bought or sold by whoever transacts in the stuff nowadays, we will go on living art (or whatever else we choose to do).

Jerry Saltz, the most popular critic in the history of criticism, summed it up, concisely commenting upon my work above: “Art is for the ages, not only meant as explicitly on-message, intervention, or for only one particular age. Artists know what they are doing but are also helpless to not do what they are called to do. No artist owns the meaning of their work. Kenny Schachter is compelled by the forces that compel us all to do what it is we do. The market is noise.” Thanks, Jerry.